Who Wants DILF? And Other Questions.

On identities, patriarchy, and the trans and/or feminist value of never being sure.

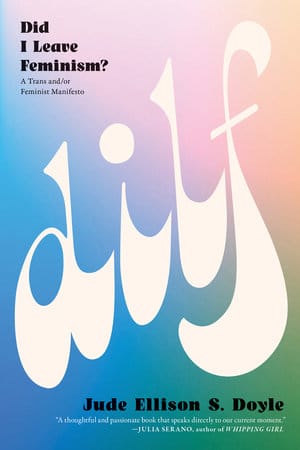

At last! It's finally pub day for DILF: Did I Leave Feminism. You can now buy it on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or through your local independent bookstore via Bookshop.org. If you're feeling particularly saucy, you can also buy the DILF perfume from Black Phoenix Alchemy Lab.

If you're on the fence, well, when has a lengthy essay that is mostly about my Feelings ever gone amiss? Here's one now.

The title of DILF — my third book of non-fiction, which comes out today — is a question. It’s Did I Leave Feminism: Did my transition make me less of a feminist, does feminism itself depend on being a woman, are transmasculine people covered by feminism or is that misgendering, can I belong to the movement I care about while living inside the body I want and need?

Those are the questions I started with, and to be honest, I thought they would have easy answers. Feminism is for everybody, as bell hooks said; if it wasn’t for trans people, then it wouldn’t deserve the name.

It wasn’t until I was several drafts in that I realized the book was something other than an easy answer to a stupid question: It was a survey of the places where trans theory and feminism rub up against each other and create friction, a document of the very deep wounds inflicted on trans people in feminism’s name, and of the distrust that has arisen in their wake.

It was a book that would make every single member of every single potential audience at least a little uncomfortable: Cis feminists would be asked to consider how they’d hurt marginalized people in the name of self-protection, and trans people would be asked to consider that the movements and thinkers that were being invoked to hurt them had often started out by making some pretty good points.

Why am I doing this to myself? was the question I asked, more and more often, as DILF took shape. Who’s going to understand what I’m saying? Who’s going to try? Who’s going to hate it, who’s going to misread it, and why, and how bad will it be? Writing any book feels vulnerable, but this one was excruciating; it was the first book published under my real name. It was a book that centered on my fears of un-belonging — the sense that I was pieced together out of two contradictory identities, and anyone who could accept one half of me would necessarily reject the other half, so that I wound up belonging nowhere, with no-one.

You write a book like this as a way of placing a bet, making yourself believe that someone will show up for you, someone will care about what you have to say. If no-one did, it was going to hurt. A lot.

And then, finally, when I managed to cut down through all the whining and self-consciousness, there was the question that actually mattered: Who does this book serve? Who am I trying to help here, and how do I mean to help them?

You, I hope, are the answer to that last question. But to explain this, I need to tell you why.

Complicated can be a weasel word. People use it to worm their way out of accountability, or to pretend that a lack of moral clarity is the same thing as insight. Why aren’t you doing the right thing? It’s complicated. Why are you doing the wrong one? It’s complicated. Is transphobia right, or wrong? It’s, guess what, complicated. You know the drill.

It’s not actually very complicated to assert that trans people are human, and immiserating or marginalizing or killing us violates our human dignity. Women are also human, whether they’re cis or trans, and sexism and misogyny are also wrong, for that same reason. If you’re looking for a book that helps you to it’s-complicated your way out of taking a stand, you won’t find it here.

But I do believe that complexity and complication are valuable, especially right now. In chaotic and frightening times, it is more tempting than ever to find some simple, absolute belief system and cling to it as your protection against the world. Doing so makes you dangerous, and not only to yourself: The authoritarian personality scale, developed by Theodor Adorno as a way to figure out who goes Nazi, finds that intolerance of ambiguity, more than any other trait, is associated with fascist sympathies. If you can’t handle not being sure, then you are forced to lash out at the world, to make it conform to your preferred certainties.

Much feminist transphobia started off that way — as a refusal to admit complication. Cis radical feminists had a clean and simple analysis of gender — that it was a form of oppression; that woman is not an essence, but the name we use for someone who is oppressed on the basis of having a uterus — that was thrown into confusion by the reality of trans people’s existence.

Those feminists could have corrected their theory with one added complication (sexism and misogyny aren’t parceled out based on your chromosomes or reproductive anatomy — the vast majority of people don’t ever see those things — but on the basis of being perceived as a woman) or with several complications (a patriarchal culture upholds masculinity as intrinsically superior, and therefore deals out some form of misogyny to anyone deemed feminine, including many men) or they could have realized that binary gender, itself, is an invention of the patriarchy, and that instead of defining feminism as “women’s liberation,” it might be more accurate to see it as the struggle of gender-marginalized people against patriarchy itself.

They didn’t. They decided that the theory was right, and the people were wrong, and set about trying to eliminate the people, so that they didn’t have to do any more thinking. It wasn’t a few fringe assholes doing this, either: Adrienne Rich consulted closely with Janice Raymond on The Transsexual Empire. Gloria Steinem took part in the trashing of trans tennis player Renee Richards. Even feminists who never went full TERF are often implicated: You don’t get to admire bell hooks without learning that she asked tone-deaf questions of Laverne Cox, or wrote weird shit about Paris is Burning. (Said weird shit includes the startling admission that hooks used to cross-dress to go out with her boyfriends: “Don’t worry when we come home I will be a girl for you again but for now I want us to be boys together,” hooks wrote in a diary entry. Hmm!)

Many of the feminists I admired as a younger person were deeply complicit in TERFdom, and I had no idea, because that’s part of the problem: Cis feminists do not teach this history to other cis feminists, but trans people teach it to each other. The list of insults and injuries keeps getting longer, but only one side is keeping count. A young trans person who sets out to study the feminist canon, or mix with cis feminists, is likely to overhear some glowing praise for people who are only ever mentioned within their own community as villains. A young cis feminist who loves, say, Andrea Dworkin’s Right-Wing Women or Robin Morgan’s “Goodbye to All That” — which I myself once loved, and cited fairly often — has no idea that, by praising those works, they’re flagging themselves as unsafe to their trans peers.

Did I leave feminism? No, but I have a significantly more complicated picture of it than I once did. I also have empathy for the teenager I once was, who needed feminism badly, and who saw it as the only movement that could help him fight the massive amounts of sexual and domestic violence he’d experienced and watched his friends and loved ones go through.

Feminism, more than most political movements, is devoted to analyzing the violence we call “private:” Violence between parents and children, between husbands and wives, between young boys and young girls, even the violence that women inflict on themselves. It insists that all of those relationships are, in fact, political, and that the “private,” domestic sphere is the place where we learn and rehearse the oppressive power dynamics that characterize public life.

Here’s the thing: Anti-trans violence often happens along those same lines. It’s cis parents isolating and shaming trans children while withholding medical care; it’s trans people afraid to come out because their partners might become violent, or their co-parents might try to take their children away; it’s the corrective sexual violence trans people experience at higher rates than cis women; it’s the violence trans people inflict on ourselves, which is so widespread that over 80% of us have considered suicide and 40% of us have already tried to die.

If you had tried to smack the Dworkin out of my hands, at age 16, or if you had shamed me for reading it, I wouldn’t have listened — I would have concluded that you were an enemy, who did not want me to be safe from sexual or gendered violence. At worst, I would have suspected that you were an advocate for that violence. I would have clung to the absolute forced clarity of my convictions, eliminated any shade of complexity or doubt, and in so doing, I would have become dangerous. It’s happened before, to better feminists than me.

But if you had told me that the violence I was facing was real, and serious, and that it was affecting more people than I knew, in ways I hadn’t yet learned about — then, I think, I would have listened to you. The conviction that human life has value, and that bigotry is therefore wrong, is indeed a simple one, which can carry you through a lot of tough decisions. But conviction is not enough. You need information. That, in part, is what DILF is trying to provide.

Writing solely to inform cis people, however, is a bummer. Trans people need feminism, too; we deserve to know that we are not guests or add-ons within feminism, but its primary architects and pioneers.

Patriarchy is the primal evil, the one that predates and creates every other. Patriarchy is the source of the dominance ethos that makes all relationships — even our earliest and most intimate; even our relationships to the people who gave us life — hierarchical and unfair and violent, always a matter of one person exercising power over another, the stronger person getting what they need at the smaller person’s expense.

The reason feminists often focused so intensely on the “private” violence of the home and the family is that they saw the nuclear family as the core unit and model for every other form of oppression: Every other unjust structure we encounter comes out of patriarchy and was built in its image. “Daddy arrived and he’s taking his belt off,” Mel Gibson said, in response to Trump’s second inauguration. A tremendous amount of the world’s suffering has come about because of the belief that power should look and operate like an abusive Dad.

So trans people are part of feminism, even though engaging with its history is likely to be painful and complicated, because we, too, are children of that terrible father. We deserve to know why Western patriarchy exercises such violent control over our bodies and futures, and whose interests are being served. Just about every trans person, quietly binding or injecting medication, has thought why is this anyone’s business? Why does anybody even care? The answer is always patriarchy. It’s because you live in a world where gender is not just a personal trait like eye color or left-handedness — it is your assigned rank in a system of power, and you are forbidden to question or change that, for fear of exposing the system itself as false. Defy your rank, and you defy the Father. The belt comes off, and we all wind up with scars.

Gender is terrible — for trans people, for cis women, and (yeah, sure, fine) even for cis men, who have to internalize that violence before they exercise it on others — but it doesn’t have to be. The goal of feminism, to my mind, is not shallow “equality,” but finding a way to live outside of patriarchal ideas about gender; it’s winning the right to exist as ourselves, in bodies and lives that fit us, rather than being bound to any stereotypical ideas of what People Like Us are supposed to do and be.

No-one gets out unless everyone gets out. That’s the problem. The Internet’s discourse cycles so often function by breaking gender-marginalized groups apart — trans mascs versus trans fems, medical transitioners versus genderqueers, cis feminists versus transfeminists, LGB versus T — but every time we split those coalitions, they get smaller, and every time a coalition gets smaller, it loses power. To patriarchy, we all share one essential trait: We are all disobedient. As long as there is a right way to do gender, someone will be doing it the wrong way, and they will be punished; until we find common ground as dissidents and deviants from the established gender system, none of us are safe.

So that’s who DILF is for: Anyone looking for a way out, anyone willing to consider how their own subjection and humiliation is bound up in those larger systems; anyone who is willing to be less comfortable, if it means being more free.

So, like... who is that? I honestly can’t answer that question. I placed a bet, by writing this book, and now I get to see if it pays off.

I’ve been a very lucky writer, so far, because I’ve never had to try for mainstream acceptability. I can focus on writing things I genuinely care about, without trying to chase the market, because the people who like my work always find a way to read it, and they tell their friends about it when they’re done. So here’s where I make my plea: If this book is for you, and it helps you, please tell someone else about it. Review it somewhere, or post about it on your socials, or add it to your queer library, or just lend it to somebody you think could benefit from it.

It’s a privilege to even get to write a book about my trans experience, and I’m very conscious that it’s not a privilege everyone receives. So I will conclude my hard sell here. If I’m not alone, it’s because you’re still here, still keeping an eye on me, two thousand words after I started this essay, and I am grateful for that. May we all keep an eye out for each other in the times to come.

To repeat: You can buy DILF: Did I Leave Feminism at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or through your local independent bookstore via Bookshop.org.

No new readings this week, but next week, there will be two: First, on Tuesday, October 28, I'll be giving a reading at my alma mater, Eugene Lang, which may or may not be online. Then, on Wednesday, the 29th, I'm going to be part of a fantastic panel on queer horror at Michigan State University, featuring Joe Vallese (editor of It Came From the Closet) and fellow contributors Addie Tsai, Zefyr Lisowski, and Carmen Maria Machado. You can definitely attend that one online.

Finally, at my other job: I'm over at the Verge, talking about trans people who can only be out on the Internet, and how Internet censorship stands to cut them off from their lifelines. It's part of a larger package on the future of being trans online, featuring some amazing writers, so enjoy.