Remind Me of the Babe: Labyrinth (Jim Henson, 1986)

Welcome to the final installment of the Halloween Special! This year, we're doing changelings and bad fairies to celebrate the impending release of The Neighbors in trade paperback.

Subscriptions are 25% off this month – $3.75/month instead of the usual $5 – so please feel free to forward this email to anyone who might like it, and to click the button:

I’ll begin with a story I’ve told many times: For at least one year of my childhood, I believed the movie Labyrinth was made specifically to scare me.

I can’t remember how old I was, but this was early grade school, so I was no more than seven. My grandparents, who babysat me, were getting sick of ending fights between me and my baby brother. So, one afternoon, my grandmother sat me down in the den, and said she had spoken to a film director, the famous and beloved Jim Henson, and persuaded him to make a movie about what would happen if I continued to pick on my brother. That educational film, entitled Labyrinth, was now available on VHS, and it starred a little girl with brown hair, who had a little brother with blonde hair, so as I could see (given my family’s identical assigned-sex-and-hair-color layout) the message was pointed. Now, I was to watch it, in hopes my morals would improve.

At a certain age, you realize that believing in magic is a choice. It didn’t seem likely that my grandmother had Jim Henson’s phone number, or that he could make entire movies at the drop of a hat just to scare specific young people. The sister in the movie was much older than I was, and the brother was much younger than my brother. I tried the charm to make goblins take my brother away; it didn’t work. Still: Reality would be a lot more fun if these things could happen. So I chose to believe.

My fondness for Labyrinth feels specific and individual; it belongs to a certain age, a certain time. It belongs to my grandparents’ brick fireplace and tiny, fuzzy television and the rust-orange shag rug where I lay on my stomach to watch it the first time. It feels that way, even though, in 2023, enjoying Labyrinth is one of the least individual things you can do.

In the decades since its release, the movie has become a pillar of (urgh) “geek culture,” particularly for elder millennials like myself. Its reputation is encrusted with fandom, memes, merchandising, tired jokes about how you can see David Bowie’s dick through his leggings. So many people have loved Labyrinth, for so long, that praising it is kind of basic. I feel embarrassed, telling you I like Labyrinth. I feel it pegs me as a type — the aging Goth theater kid who wears fairy wings to Comicon — and though I probably resemble that type more than I don’t, I don’t like being pigeonholed.

I am going to try to push past that embarrassment here — to see Labyrinth anew, cleansed of its reputation, appearing (like Bowie himself) in a cloud of glitter and fluttering gauze curtains, floor-length velvet cape billowing in the wind machine. I’m going to try to take you back to a point when Labyrinth felt personal — something I didn’t have to share with anyone, because it had been made for me. Sometimes, that’s still how it feels.

There is a reason that Labyrinth has acquired such a voracious fandom: It’s a children’s movie about someone who is no longer a child, a teenager who is reluctant to leave behind the toys and games of childhood and embrace the adult world.

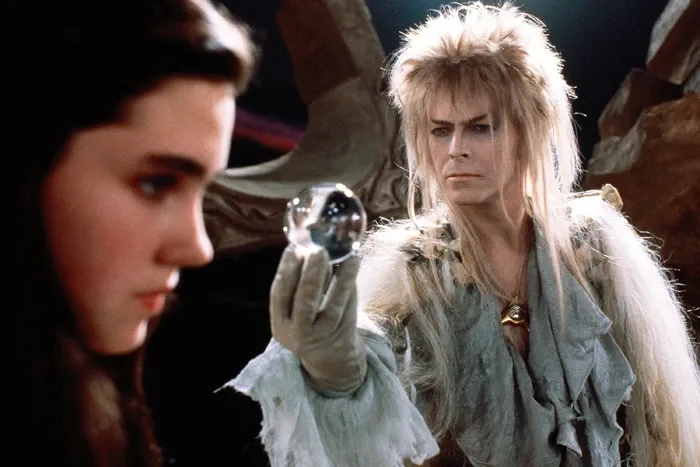

When we meet our heroine, Sarah (played by Jennifer Connelly; congrats to my grandmother on convincing me that my seven-year-old self looked like this, by the way) we see her playing pretend, in full Renaissance-Faire costume, completely alone. We see her in a bedroom cluttered with heaps of fetishistically displayed toys; her much younger brother is forbidden to touch even one of them. We’re told by Sarah’s stepmother that Sarah “never has dates,” and that she “should have dates at her age.”

Sarah is a dork, and, more specifically, she’s the kind of dork who would gravitate to over-intense fandom: Arrested in her development, in love with stuff, afraid of letting go of the things she loved as a kid, because she’s let them define her. No, not all fans are like this, but Sarah is like this, and she’s not the only one. I don’t know how intentional it is — the most likely explanation is that the movie was made by really dorky people; this is what happens when you’ve got Jim Henson, Brian Froud and a Monty Python member all on the same project — but Sarah begins Labyrinth in much the same position as, say, a 40-something writer watching Labyrinth. She’s looking backward, afraid of what’s ahead.

What is ahead of Sarah — ahead of most teenagers, really — is sex, and sex, in this instance, is embodied by David Bowie. He’s wearing a floor-length velvet cape, and leggings, and hair big enough to hold the entire 1980s, and actual fucking glitter gets thrown at the screen when he shows up; much has been said about this, and about its impact on young viewers’ developing sexualities, and I find the whole conversation a little uncomfortable, for reasons I’ll get to shortly. For the moment, just know that I know.

David Bowie is playing Jareth, the Goblin King, an otherworldly being whose main powers are looking, behaving, and singing exactly like pop superstar David Bowie. It’s an uncanny and highly intentional match between character and actor, made all the more so by the fact that Jareth is a monster. When you first see him, emerging from all that glitter, you are meant to know that he’s beautiful. You are also meant to be scared.

Labyrinth is (as you would expect, given Froud’s involvement) a fairly straightforward and faithful take on changeling mythology: There are fairies, they’re mean, they live underground, and they kidnap babies, specifically Sarah’s brother. They don’t send a goblin baby up to replace the one they’ve taken, but they do threaten to turn Sarah’s brother into a goblin, which is sort of the same idea.

Bowie/Jareth’s obsession with Sarah is what takes the movie into deeper, stranger territory. The fact that Jareth represents adult sexuality is not subtle; in the original script, he’s introduced as an adult man who convinces Sarah to let him into the house while her parents are gone. It’s a horror movie set-up, a home invasion, and rape is the clearly implied subtext — only slightly less implied in the finished version, when he just teleports into her parents’ bedroom and starts throwing his snake at her.

Yes, I said “throwing his snake at her.” It’s not a subtle allegory. To continue: Sarah has messed up by refusing to take care of her baby brother, thereby getting him Hellraiser’d. She now has thirteen hours to find him and bring him back to the mortal world. Hinging a heroine’s moral worth on her willingness to provide unpaid childcare is a questionable choice, to be sure, and I once had a conversation with a feminist who was furious at Labyrinth because she considered it natalist propaganda about how young women had to give up their hobbies and interests and prepare for motherhood. I don’t agree with her, but I do see where she got the reading.

However, the baby is not the whole story. Sarah’s real “sin” (if you can call it that, and I wouldn’t) is that, despite not wanting a baby, she is beginning to be curious about adult romance and sex — she is bewitched by Jareth, willing to play with and pursue the energy he represents, even though he frightens her, and even though being with him would mean giving up the world she knows. Jareth steals children and changes them, and Sarah spends most of the movie trying to rescue a child, or a childhood, from his clutches, but the brother is just a symbol. The childhood she is trying to preserve is her own.

Leaving aside questions of fandom and arrested development, I think most teenagers enter a phase like this: Obsessed with sex but terrified of it, not remotely ready for an intimate relationship but consumed with daydreams of what an adult relationship might be like. What makes Bowie so unforgettable in the role is that he embodies both the dream and the nightmare; he is beautiful and terrible, seductive and monstrous, in equal measure and at every moment. This is not a mistake. It’s probably not acting, either.

Shortly after Bowie’s death, I (along with many other people) learned that he actually did have sex with at least one fourteen-year-old girl, a fan named Lori Mattix. She seems to remember the encounter fondly — “I found myself more and more fascinated by him. He was beautiful and clever and poised,” etc. — but this Sarah-ish gloss romanticizes a horrific abuse of power. Mattix was traded around among powerful men from the time she was thirteen years old. I’m glad she found some way to feel okay about it. That doesn’t change the fact that it should never have happened.

When you know about Lori Mattix, it is a lot harder to watch Labyrinth — and it gets only slightly easier when you know that the other main contender for this role was Michael Jackson. If nothing else, Jim Henson knew the vibe he wanted: Both men were beautiful, and ethereal, and charismatic. Both of them were also extremely fucking sinister, sometimes in the same ways.

What saves the movie for me is its ending. Yes, adult Labyrinth fandom is basic, but Sarah confronting Jareth is still probably my favorite resolution of any movie. I’ve run into some version of it every time I’ve tried to write an ending to a story.

Many people fixate on Jareth’s speech to Sarah, about how everything he’s done has been for her, as proof that the movie is somehow romantic, or that Jareth is a redeemable character. But if you scrub off the lyricism of the dialogue or the magnetism of the performance, what he’s actually saying — you asked for the child to be taken; I took him, etc. — is what every guy like him says when confronted or called out. You wanted this. You were responsible. You asked for it.

Sarah completely rejects him. Slowly, calmly, word by word and step by step, she advances on him and shuts him down. Nothing he says or does can stop her from saying what she needs to say, and she doesn’t even need to raise her voice to say it. It’s shockingly powerful — especially in a movie aimed at pre-teen girls, especially in the mid-1980s. Even if David fucking Bowie himself tries to strong-arm you or blame you for his bullshit, Labyrinth says, you still don’t have to listen to him. In this scene, Jareth is both an abuser sweet-talking his victim and a fantasy pleading for his right to exist. He is a fear and a dream, but Sarah is the dreamer. She can end him by seeing him for what he is: You have no power over me.

“Adult sexuality,” or more precisely being sexualized by adult men, really is a threat to teen girls, and to many other children. But Sarah cannot stop growing up just because Jareth scares her. Sarah’s adulthood does not consist of being willing to care for a baby (yuck) or of going on dates with boys; it comes from knowing her own power, being willing to say what she will and will not tolerate. It comes from honoring herself and refusing to be intimidated or made small by others: My will is as strong as yours, and my kingdom as great.

All that, and she doesn’t even need to give up the toy collection. Sarah leaves her state of arrested development, but she does not emerge as a full-grown woman. She ends the movie still a teenager — an age that is no age and all ages, where you can be five years old in the morning and fifty by the afternoon. The pieces of the labyrinth that she’s loved, the pieces of her childhood that she’s not ready to lose just yet, come with her into the real world. They just don’t control or define her. They are there should you need us — should you need us, the way my grandmother’s orange shag rug and brick fireplace are still here, with me, even though both my grandparents have died and their house was sold long ago.

You don’t have to lose yourself when you get older. You don’t have to lose your stories — not even when the stories get older along with you, not even when they start embarrassing you, or when you learn things about them that make you upset or angry or sad. What you love is not a thing. It’s not stuff. It’s a moment, and who you were in that moment; it’s a memory of a time you knew joy. Your moments belong to you, because they are you. Everything else is set dressing. You are the myth, the story, the fairy tale; you are the world you carry around.

Labyrinth is streaming on Hulu.

At my other job: A question that still haunts me (and, presumably, LL Cool J): How does LL Cool J survive the movie Halloween: H20?

That's it for the Halloween special this year. There are still a few days left to subscribe for cheap, so tell your friends and click the button: