That White Dead World

Exploration and horror in the polar wastelands.

In July of 1911, a 24-year-old zoologist named Apsley Cherry-Garrard set off with four other men to do something that had never been attempted before: A journey, on foot, across the Antarctic, in the dead of winter.

Winters and summers are flipped, in the Southern Hemisphere, so July was the coldest and darkest the Antarctic ever got. The sun disappeared for months. The men spent twenty-four hours a day in darkness — walking, endlessly, across a trackless void, in temperatures of minus sixty degrees or less. It was often less.

“That men should wander forth in the depth of a Polar night to face the most dismal cold and the fiercest gales in darkness is something new,” wrote the expedition’s commander, Robert Falcon Scott, in his journal. Scott himself would be dead in a year’s time, and this optimism was part of the reason why — the notion of a Winter Journey was new, Cherry-Garrard cheerfully notes in his memoir, because it was a massively bad idea. Just how bad can be garnered from the memoir’s title: The Worst Journey In the World.

Consider: These men were not only walking, they were hauling, because all the equipment and food for the journey had to be carried on a sledge. The main expedition was well-supplied with ponies and dogs, which they used to haul sledges, and sometimes used for food — the ponies, in particular, were dropping like flies, and there wasn’t much else to do with them — but for the Winter Journey, the men harnessed themselves to the sledge, and pulled it.

It was hard work, and they sweated prodigiously — “I never knew before how much of the body's waste comes out through the pores of the skin,” Cherry-Garrard wrote — but all that sweat hit the polar air and froze. “It passed just away from our flesh and then became ice: we shook plenty of snow and ice down from inside our trousers every time we changed our foot-gear, and we could have shaken it from our vests and from between our vests and shirts, but of course we could not strip to this extent.”

The layer of ice turned their clothes and sleeping-bags — they slept outside — into “armor-plate,” stiffer, but also heavier, so the load only got heavier as they walked. At one point, Cherry-Garrard, writes, “I raised my head to look round and found I could not move it back. My clothing had frozen hard as I stood—perhaps fifteen seconds. For four hours I had to pull with my head stuck up.” After that, the men made sure to tuck themselves into their sleeping-bags bent over, in the position they would use to haul the sledge during the day.

“The horror of the nineteen days it took us to travel from Cape Evans to Cape Crozier would have to be re-experienced to be appreciated; and any one would be a fool who went again: it is not possible to describe it,” Cherry-Garrard wrote, describing it more than adequately. “The weeks which followed them were comparative bliss, not because later our conditions were better—they were far worse—because we were callous. I for one had come to that point of suffering at which I did not really care if only I could die without much pain.”

What bothered Cherry-Garrard most, he said, was the darkness: “I don't believe minus seventy temperatures would be bad in daylight, not comparatively bad, when you could see where you were going, where you were stepping, where the sledge straps were, the cooker, the primus, the food; could see your footsteps lately trodden deep into the soft snow that you might find your way back to the rest of your load… [or] could read a compass without striking three or four different boxes to find one dry match.”

But the endless night was only one of the ways the Antarctic could blind travelers. Summer offered another: Endless day, on a white on white on white landscape of snow and ice that refracted sunlight back into the explorers’ eyes, so that any man who went out without protective goggles would go snow-blind. This is something you learn, reading Apsley Cherry-Garrard, or any of the many horrific (and fictional) accounts of polar travel that came after him: Whiteness can be darkness, too.

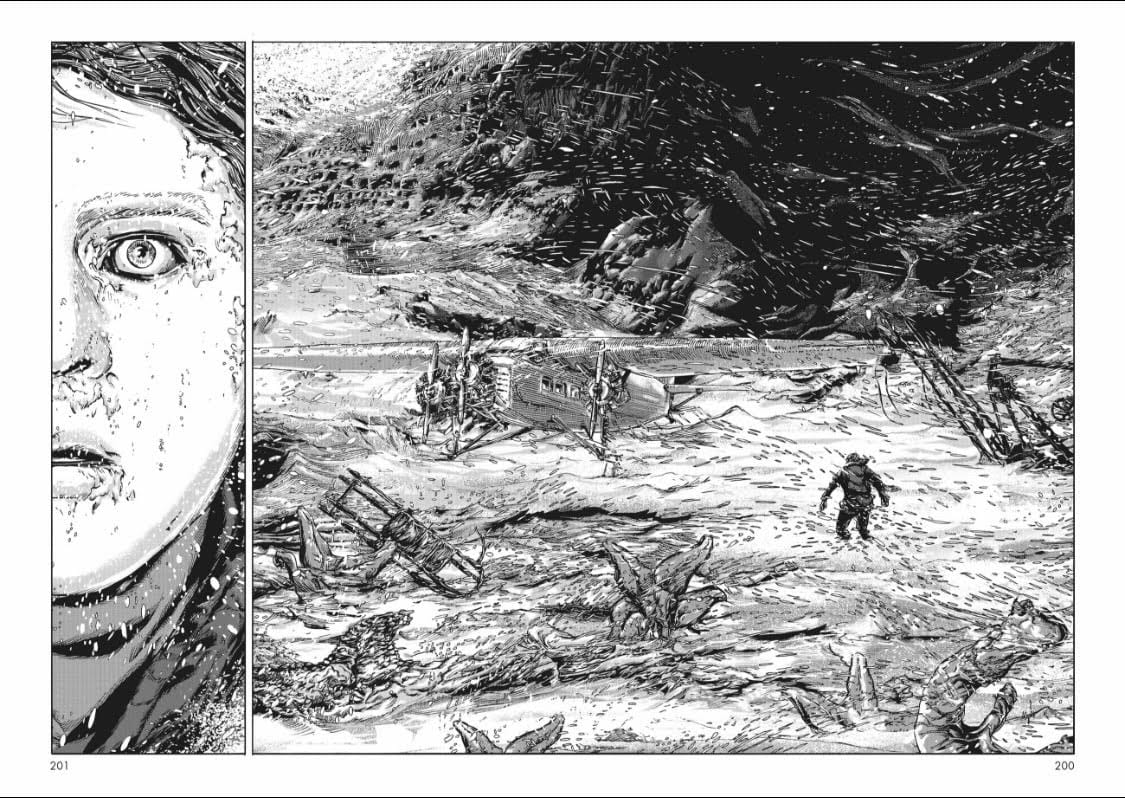

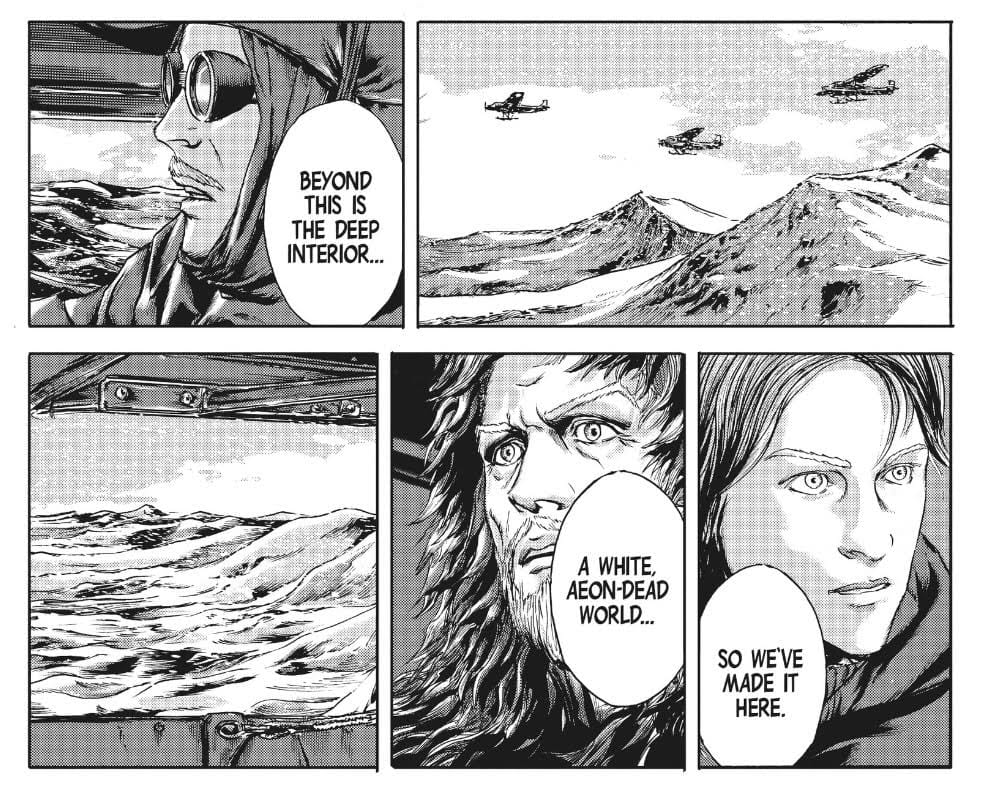

It’s hard for a 21st-century reader — or a 21st-century horror reader, anyway — to read Cherry-Garrard’s memoir without being reminded of At the Mountains of Madness, H.P. Lovecraft’s fictional tale of a doomed Antarctic expedition. The Worst Journey In the World is, in fact, name-checked in Gou Tanabe’s two-volume manga adaptation, though not in the original text — Lovecraft cites names you will recognize from Cherry-Garrard’s text (Scott, Shackleton, and Amundsen, the Norwegian explorer who beat Scott to the South Pole a few weeks before Scott and everyone on his doomed Polar Journey starved to death) but does not directly acknowledge the debt, which seems to have been tremendous.

I will confess that it’s been a while since I read the original At the Mountains of Madness, and that I retain very few details, apart from the (goofy, I thought) bit about the explorers being menaced by giant penguins. Lovecraft is a slog for me, not (shamefully) because of his racism, but because of his prose, which piles overheated adjectives onto overlong sentences until — like a snow-blind explorer, hauling a sledge — I can’t tell what the fuck’s going on. When the Lovecraftian mythos scares me, it’s typically in the hands of another writer, or in adaptation. Tanabe’s manga is both, and I liked it a ton.

Those evil mutant penguins are one of Mountains’ most direct links to Cherry-Garrard; the purpose of the Winter Journey was to collect eggs during the winter laying season of the Emperor penguin. It was thought that, because the Emperor penguin was a “primitive bird,” its embryos might afford some insight into how feathers had evolved from scales, and thereby solidify the evolutionary link between birds and reptiles. Cherry-Garrard seems to have truly loved penguins, and claims the whole expedition was worth it just to study them close up. He also says that, after he returned to England as the lone survivor of the Winter Journey, and handed his eggs over to a museum for further study — specimens for which he had suffered, seen friends die, and nearly died himself — the scientists at the museum didn’t recognize him, and kept him waiting for hours in the lobby.

Cherry-Garrard, unlike Lovecraft, is a very funny writer. His conclusions are often bleaker, precisely because Cherry-Garrard himself refuses to moan over how bleak they are.

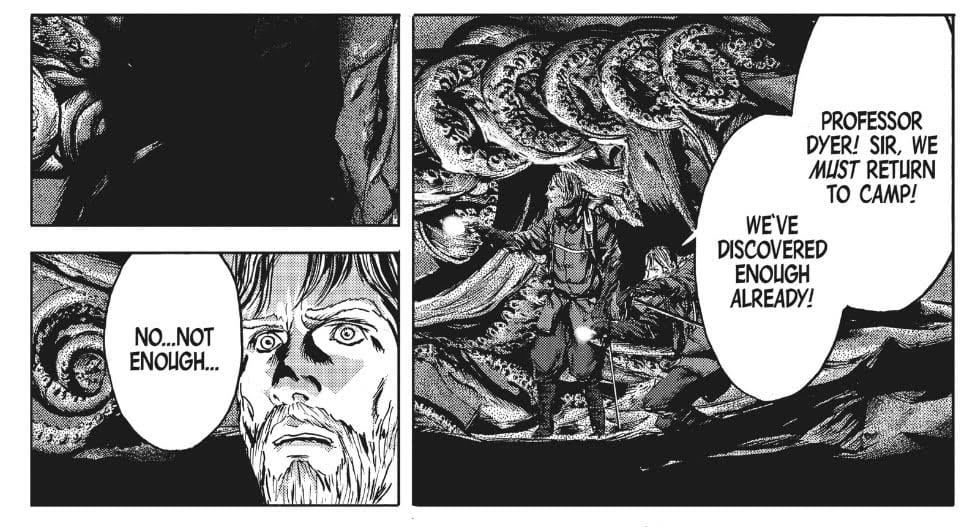

Well: At the Mountains of Madness is also about a team of scientists, and the extreme lengths they will go to for knowledge, even when that effort seems completely unjustifiable by the standards of the sane world. It is also about evolution, and studying the primitive creatures of the Antarctic to chart deep time. What Lovecraft’s doomed scientists discover is that the time is deeper, and the creatures less primitive, than they had any right to expect.

Deep within the supposedly uninhabitable Antarctic waste, there is an abandoned city, which holds the history of ancient alien races that settled Earth long before life began — aliens who, in fact, seem to have created life as we know it. This being Lovecraft, the alien settlers are bloodthirsty, and abominable, and a lot less extinct than you’d hope.

Tanabe does an admirable, even stellar, job of visually adapting the book’s mythology, which entails the millennia-long history and internecine warfare of several competing alien civilizations. It’s hard to make compelling character drama when all your actors look like fancy starfish or malevolent tapioca pudding, but Tanabe brings Lovecraft’s supposedly unimaginable creatures to life so well that he barely even needs text for the panels. Even the penguins, goofy as they are, turned out pretty scary.

What really sticks with me, though, is not the evil-invertebrate space opera. It’s a long, excellent passage of the scientists exploring the ruined towers of the wasteland, going deeper and deeper underground, in defiance of all the steadily mounting evidence that what they’re looking for is not something anyone wants to find. Why do they do it? Why keep walking, when you know you’re walking toward death? To know; to see what’s at the bottom of everything, to find the unspeakable truth that history and biology and religion have been hiding.

The desire for knowledge, in a Lovecraft story, is a disease, a kind of mania. It can only ever end in the knowledge of one’s own insignificance, and the futility of all human endeavor. It’s tempting to dismiss that kind of conclusion as pointlessly bleak or anti-intellectual — but Apsley Cherry-Garrard, sitting in a museum lobby with a couple of penguin eggs, found out the exact same thing.

I make my living as a humble newsletter merchant. This essay is free, but if you'd like to support my work, I would really appreciate your subscription. Here's the button:

If Worst Journey inspired Mountains of Madness, the chain of evolution hardly stops there. Lovecraft’s story inspired a thriving sub-genre of polar horror, worming its way through decades and mediums: Cherry-Garrard’s book (1922) becomes Mountains of Madness (1931) which becomes John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” (1938), which is adapted into John Carpenter’s The Thing (1982), which became the “Ice” episode of The X-Files (1993), which recombines with actual history to produce Dan Simmons’ 2007 novel The Terror, which in turn became the 2018 prestige-TV miniseries The Terror, and all of this seems to have taken a turn and come around from a new angle in True Detective: Night Country last year.

The core elements in each story are the same: A group of men (it’s always men) who are scientists (always at least some scientists) and mostly or entirely white (the whiteness will be important) make camp in the Arctic waste and immediately discover some Thing from Another World, a Thing which is so far beyond the understanding of their science that it has no trouble slaughtering them all. Polar horror is, in other words, colonialist horror: A bunch of white men set out to explore an “uninhabited” land, and immediately find out that it is inhabited, and that they are not welcome.

Lovecraft, being a racist white man living in the first half of the 20th century, could play this fear straight. The Terror — and Night Country, though it would be hard to talk about much without spoiling it — are the most recent adaptations, and as such, bear the burden of self-awareness, which is why both spotlight the perspectives of Native women.

Knowledge, from the white male colonialist point of view, is conquest; it is a way of seizing a piece of the world, making it your own, making it subject to your rules. Rape, particularly rape of colonized subjects, is the same thing. Indigenous and Native American women traditionally bear the burden of both, which is why, to this day, sexual assault rates among Native women are drastically higher than they are in the general population.

The Terror and Night Country do not deny us the familiar pleasures of their genre — the unspeakable horror out on the ice, the white guys flailing and starving and going mad with horror — but they surround them with the silent gaze of Native women, who are either ignored (as in Night Country, where they are overlooked support workers at the research station) or literally silenced, as in The Terror’s meaningfully named Lady Silence, who is missing her tongue. We are always seeing these men through the eyes of the Other; we are always being reminded that the land is not “uninhabitable,” but that these specific men do not know how to inhabit it, and are not willing to listen to those who do.

The failure of the polar expedition in The Terror is not some cosmic refusal of Man’s significance. It’s simple human error: The steam engines which were supposed to help the ships break through the ice were intended for trains, not marine use, and so they broke. The tinned food intended to help them survive the winter was canned in lead, and poisoned the men as they ate it. Some of these problems were foreseeable, some unforeseeable, but they were all mistakes. They arose, not from cosmic evil, but from the arrogance it takes to believe you can go where no man has gone before — the arrogance, that is, to assume no men have gone there.

“They were men!” Lovecraft’s narrator exclaims in horror, confronting the tombs of the starfish aliens. “They had not been even savages—for what indeed had they done?” The aliens, however fearsome they may seem, were explorers of the polar wastes, like our heroes; they were doomed, like our heroes; in fact, the two groups even shared a profession: “Poor Old Ones! Scientists to the last—what had they done that we would not have done in their place?”

It was one final indignity heaped on Apsley Cherry-Garrard: To find himself, after all he’d been through, transformed into an intergalactic starfish. Yet there is something tragic here. For Lovecraft, the realization that we are not alone in the cosmos can only provoke feelings of dreadful insignificance. The ultimate horror is to find that your own personhood is not unique or special, and that even people who don’t look like you are people. Or “men,” I guess, to use the term men use.

It seems like a cheat to reduce all these stories to a political metaphor. Applying the lenses of whiteness or patriarchy or colonialism supples some insight, and maybe even makes you look clever, but it does not explain away their primal power.

I first became interested in polar horror when I moved to upstate New York, an area that is famous for its long and brutal winters. Snow and ice here have an urgent, personal force, like a dark God demanding to be propitiated, and I thought the experience would be less unbearable if I could find it in art. What occurs to me now, though it didn’t at the time, is that I was grieving — grieving the warmer city I had lived in for nearly two decades, grieving the life I thought I would have, grieving the person I had been, before I became a parent, and had to choose my location based on things like livable rents and good public schools. The winter was the part of the move I dreaded, and so it came to stand in for what I had lost.

When I started reading Cherry-Garrard’s book, this summer, I was also grieving. This time, the loss was less abstract — the death of my father. Grief lets you do ridiculous things like compare your life to a polar expedition, even when your actual journeys are not any longer or more uncomfortable than the trip to Wegmans. The image recurred, and kept compelling me — all those men, lost, cold, pressing on through the alien dark, because there was nothing left to do but keep walking.

Metaphors of conquest aside, the Antarctic, as Cherry-Garrard encountered it, actually was uninhabited — not only that, but uninhabitable; a place where the world closes up and says no. Everyone winds up in those places, sometimes. Everyone who winds up there has to keep going, because the only other option is to stop.

It was human error, too, that doomed Scott’s Polar Journey. As Cherry-Garrard tells it, the real purpose of the mission was the science — reaching the South Pole was just a big, showy accomplishment meant to attract headlines and funding. Therefore, Scott saved it for the end of the expedition. By that time, they were running low on food, and could not budget in extra for an emergency. The men selected for the Polar Journey were the same men who had been on the Winter Journey, and they had already been pushed beyond the limits of their endurance. Cherry-Garrard was in particularly rough shape, which is why he stayed behind.

Scott and his team did reach the Pole — though Amundsen beat them to it — but on the way back, an unexpected blizzard snowed the men into their tent for a little less than two weeks. They did not have enough food or supplies to outlast it. Scott and his men died, snowed into their tent, almost within sight of base camp and safety. Cherry-Garrard was one of the men who discovered the bodies. He does not say what condition they were in, though he makes a point of saying he won’t describe them.

Man vs. nature has always been my favorite of the classical plot conflicts, because it is unwinnable: It is in man’s nature to die, and nature is always what does us in, one way or another. Yet the world which annihilates us also takes exquisite care of us, right up until it doesn’t. It gives us a breathable atmosphere, rivers and lakes of drinkable water, dirt which grows food that we can live on, until we die and become food for something else.

The revelation that terrified Lovecraft is, to me, something like religion: We belong to an order that is bigger than any of us, and which we can never entirely comprehend. The universe is indifferent to our individual desires and ambitions, but we do have the hope of transcending our individuality, of learning to see ourselves from the viewpoint of a species, or a biosphere, as conduits that Life uses to continue itself. Whether or not we ever reach our intended destinations, the universe flows through us, and will flow on after us into newer and more surprising forms.

Cherry-Garrard was not unaware of the metaphorical dimension of his story. He ends his book on it: “If you march your Winter Journeys you will have your reward,” he tells us, “so long as all you want is a penguin's egg.”

They never did find anything useful in the penguins’ eggs, is the thing. The connection between reptile and bird had to wait for other means of confirmation. All that suffering, all those deaths, turned up a dead end, and it is with this final, deceptively cheerful joke — it was all for nothing; there is no point to any of this — that Apsley Cherry-Garrard leaves us, and fades away forever into the cold white dark.