Poptimism Ate Itself

Oh Christgau! Up yours!

Welcome back! It's a long newsletter, but these are short book announcements:

My non-fiction book DILF: Did I Leave Feminism is available for pre-order anywhere you buy books. It comes out October 21, but I'll be in NYC on October 14 for a conversation with Heather Hogan, and we'll have books there for you to buy early. Get tickets and learn more here.

Be Not Afraid #3, the third issue of my horror comic series with Lisandro Estherren, is on stands now. Issue #4 will be on sale October 1.

It's rare, these days, to have the luxury of getting upset about anything that isn't fascism. This is why I was pleased, a few weeks ago, to run into a social-media ruckus that felt like a rerun from 2013 — the anger circling around a Kelefa Sanneh piece called “How Criticism Lost Its Edge.” The piece is old now, in Internet time, and I will almost certainly offend several people I like and respect by responding to it. Still, the only alternative to talking about it is talking about everything else, so here we are.

There are no “mean” critics any more, Sanneh writes, and most critics are simply boosters of whatever they cover — which tends to be whatever is most popular in the mainstream. Even publications that supposedly exist to provide an alternative end up reflecting the market more often than not, and (here’s where it gets ugly) certain critics consider reflecting the market to be the moral and artistically correct decision — cf. the long fight behind the scenes at Pitchfork to get them to cover Taylor Swift, a move which was resisted by Pitchfork’s founder Ryan Schreiber until 2017 and the release of Reputation.

Swift hangs over this piece like a miasma, as Sanneh’s preferred example of the beige, music-flavored paste that now receives widespread (un)critical validation. In one damning section, he notes that the sole negative review of her Tortured Poets’ Society had to be published anonymously, out of fear for the writer’s safety. I will — unfortunately — get to that later.

By now, though, you are beginning to recognize that the Sanneh piece was an attack on the critical school known as “poptimism;” a bizarre choice, given that Sanneh himself made his bones as a poptimist, but we’re all entitled to regret the way we spent the 2010s. I sure do. The briefest way to describe poptimism is that it argues mass-produced Top 40 pop music is just as deserving of critical attention as rock bands fronted by sweaty white dudes. The more complex way to put this is that validating those sweaty white rock dudes — while casting rap, or R&B, or bubblegum pop, all of which are significantly Blacker and/or gayer and/or more likely to be fronted by women, as intrinsically inferior — is an example of racist, sexist and homophobic bias in music journalism.

The absolute least complex way to put this is that pop is good, because lots of people like it, and some of those people are marginalized, so liking pop is therefore a necessary qualification for being feminist or anti-racist or a queer ally, and that preferring boring obscure stuff like jazz or ambient or metal or folk or punk or (increasingly) any form of rock at all is for pretentious boring snobs, who are probably bad, hateful, bigoted people because their tastes don’t mirror the majority’s. Unfortunately, that version of poptimism — which I will dub “vulgar poptimism,” just to separate it from its smarter and more nuanced precursors — is what caught on and became the dominant framework for all cultural discourse (not just music; YA fiction, IP-driven movie franchises, etc. also fell under the “pop” banner) in the Obama era.

I’m going to emphasize, before going in, that there are excellent writers and thinkers working under the banner of “poptimism.” Some are its standard-bearers. Ann Powers, for instance, is a wonderful person and a great critic. Maura Johnston is a wonderful person and a great critic. Neither woman practices vulgar or reductive poptimism of the kind I’m talking about here. Moreover, I think there are criticisms to be made of Sanneh’s piece, and I plan to make them. One point made over and over, in the social-media reaction to the piece, is that culture writing, as an industry, has basically collapsed over the past decade, and that it’s poor form to blame critics for the fact that there are no more critics these days. I agree.

But I also don’t think Pitchfork should cover Taylor Swift. I think the whole purpose of a publication like Pitchfork is to highlight not-Taylor-Swift artists. I admit: Part of this is that I just don’t like her music, which is a point I hope not to belabor. I agree with Schreiber that it is “bland and uninteresting,” an opinion that would be easy to write off as phallocentric rockist arrogance were it not for the fact that it is shared by Courtney Love. I agree with Sanneh (I suspect) that she is an example of the mediocrity that gets elevated when “likability” or mass appeal becomes the criteria for good art.

But the other part of my objection, and the more important part, is the fact that Taylor Swift already benefits from a massive apparatus designed to make her music literally inescapable. The whole point of a Taylor Swift album is that, no matter who you are, you will hear at least half of it — before NFL commercial breaks, in the commercials being cut to, in the bodega, at the mall, hummed by your coworkers, coming out of the windows of passing cars — within the first six months of its release. You do not need a critic to help you decide whether to listen to the new Taylor Swift album: You’ve already heard it. You can’t not hear it. To make the kind of music no-one can not hear — that’s what pop stardom is.

Poptimist critics will tell you that they do not exist to give the rubber stamp of approval to anything that makes money. They will tell you that they, like all critics, have specialized knowledge of the industries and genres they cover; that a critic is not merely someone with opinions, but someone with enough insider knowledge and expertise to translate the art form to the public. But that contradicts the basic thesis of vulgar poptimism, which is that pop deserves coverage because it is a democratically chosen music of the masses: Poptimism sounds like populism for a reason. You’re left with two irreconcilable claims:

1) Music is a complex art form, which requires some specialized knowledge to appreciate; the critic is an expert and public educator who teaches us how to truly listen to the music we hear.

2) Music exists to be liked, and the number of people who like a piece of music reflects how good it is, and pop music is liked by the most people, which makes it the best; the critic exists to interpret and proclaim the will of The People, as determined by Charts.

If (1) is true, then the critic — who has the specialized knowledge of music necessary to explain its many layers — should probably focus on covering difficult, formally innovative, divisive, or obscure music, which the public might not appreciate without their assistance. If (2) is true, then we don’t need critics — “liking” a piece of music is the ultimate judgment of its value, and the critic is just an unnecessary middleman between the listener and the music they like.

In the first case, you don’t need to cover Taylor Swift at Pitchfork because it’s a platform specifically intended to review smaller acts; in the second case, you don’t need to cover Taylor Swift at Pitchfork because you don’t need Pitchfork. This is the not-so-subtle thrust of Sanneh’s piece: That critics went from guiding the public’s taste to reflecting the public’s taste, and thereby inadvertently wrote the rationale for their own non-existence.

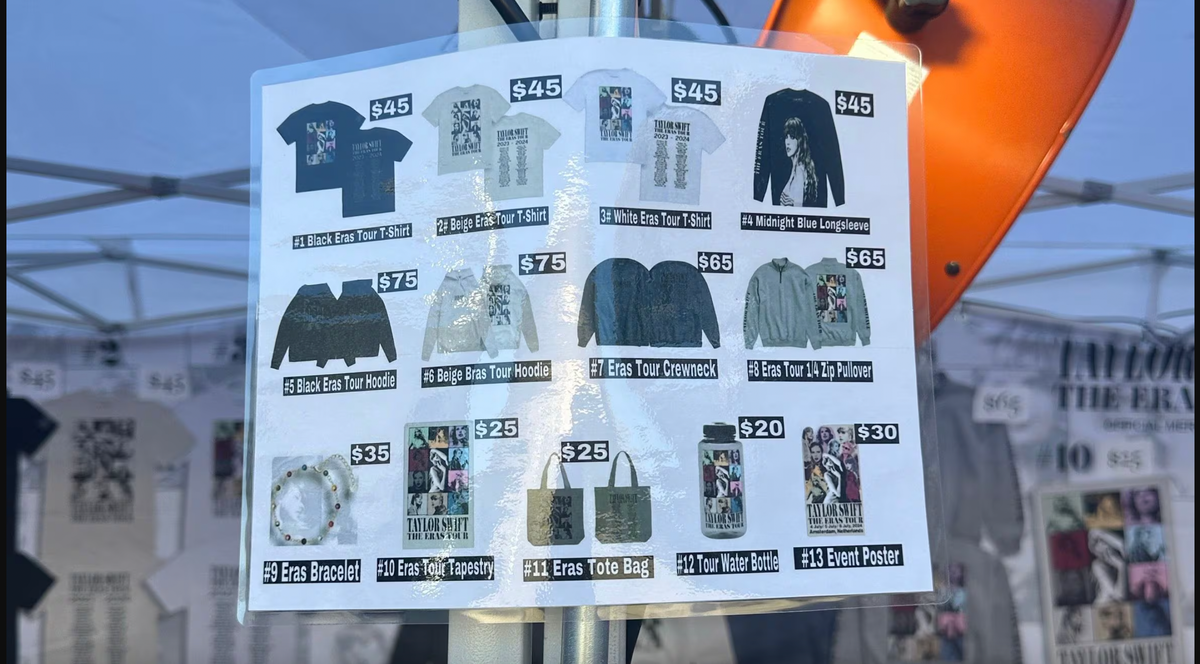

I wish I disagreed with that more than I do. The truth is that the vulgar poptimist ideal of letting people like what they like is also the preferred state of affairs for capitalism — cultural value collapses into market value, so that the amount of money something makes is the only necessary judgment of its worth. In this formulation, pop stars are not predominantly artists, or even entertainers; they are brands, with billions of dollars riding on them, tasked with selling records and tickets and t-shirts and live-in-theater concert experiences and makeup and streaming services and licenses so that Target and Apple and Coke and Pepsi can sell even more products with commercials that use their music. It does not matter whether I connect emotionally with Taylor Swift’s music, or whether anyone does; emotional connection is a secondary concern, useful only insofar as it generates consumer loyalty and moves more units.

You can draw a direct line from that to the elimination of culture journalism and the rise of AI slop, which doesn’t even pretend to be offering real human creativity or emotion. But the fact that things are bad now does not imply that pre-poptimist criticism was any better. To explain this, I will have to take a detour, to a topic dear to my heart: My eternal, burning, bone-deep hatred of the Dean of American Rock Critics, Robert Christgau.

Sanneh’s piece cites Christgau, several times, as an example of the good, mean criticism we’ve lost. Christgau is – like every critic Sanneh takes time to praise, and (perhaps not coincidentally) like Sanneh himself – a man. This is one problem. The second is that you can scarcely find a man, or a critic, less deserving of praise than Christgau is.

To fully explain what is wrong with him, I need to point you to perhaps my favorite item from his catalogue: The full review of Bjork’s 1995 album Post.

This well-regarded little item rekindles my primeval suspicion of Europeans who presume to "improve" on rock and roll (or for that matter Betty Hutton, originator of the best song here). I don't miss the Sugarcubes' guitars per se so much as their commitment to the groove, which--sporadic though it would remain, Iceland not being one of your blues hotbeds--might shore up the limited but real intrinsic interest of her eccentric instrumentation, electronic timbres, etc. Then there's her, how shall I say it, self-involved vocal devices. Which brings us to, right, her lyrics, which might hit home harder if she'd grown up speaking the English she'll die singing, but probably wouldn't. Anybody out there remember Dagmar Krause? German, Henry Cow, into artsong and proud of it? Well, take my word for it. She was no great shakes either. But at least she had politics.

The discerning reader will note that this is not “mean” — it’s wrong. Glaringly, hideously, memorably wrong; the kind of wrong that follows a critic for the rest of his career. It tends to get lost in the wash, with Christgau, because he was this kind of wrong every time he felt intimidated by a female musician, and he was intimidated by them most of the time.

It’s important to note the sheer size of the boat Christgau was missing: Bjork’s first solo albums, Debut and Post, basically rewrote the DNA of “alternative” music by incorporating underground electronic and dance beats that Seattle grunge bands wouldn’t touch — a poptimist triumph, by any reasonable standard, and one that would be imitated by everyone from the Smashing Pumpkins to PJ Harvey to goddamn Madonna in the years that followed. Homogenic, her next release, pioneered the minimalistic, icy sound that was shamelessly ganked by Bjork superfan Thom Yorke three years later on Kid A, and which would go on from there to conquer the entire indie-speaking world.

Christgau gave Homogenic a one-line review, and that line was a quotation of a lyric he evidently found laughable. Was it about gender? Well: Kid A got a rave review calling it “an imaginative, imitative variation on a pop staple: sadness made pretty.” You do the math.

It’s not just Bjork. You can hardly find a trailblazing female musician Christgau hasn’t dismissed, condescended to, or slimed by reviewing her body or sexuality rather than her actual work. If you tried to compile a list of every woman he degraded, underestimated, or just plain refused to review because he didn’t want to fuck her, you would wind up accidentally reverse-engineering a list of history’s greatest bangers. I know, because I did:

I don't care how many positive Fiona Apple reviews you write -- if you gave a frowny-face-emoticon review to "Criminal," you're a fucking idiot.

Poly Styrene, the founding mother of punk, is described in a profile as “the mulatto who leads X-Ray Spex” and “a plump young woman the color of Kraft caramel;” Christgau never actually reviewed her music. Anohni’s “I Am A Bird Now” was a “Dud of the Month,” which Christgau proclaimed was only interesting for “those convinced of the metaphoric-political centrality of transgender issues and the AIDS epidemic.” He pointedly excludes himself from their number: “Right, [she] suffers. But billions of humans have it worse… we're not obliged to empathize with any of them.”

Christgau was particularly infuriated by women who failed to hide their intelligence. Any woman who expressed a distinctive or original vision for her work was scolded for getting too many big ideas in her pretty little head: Siouxsie Sioux was “pretentious” and “disguise[d] the banality of her exoticism with psychedelic gimmicks.” Joanna Newsom’s Ys is damned for its “ambition” — “original is one thing, worth doing another,” Christgau sniffs. Kate Bush gets a pat on the head for Hounds of Love, but not before Christgau reprimands her for referencing Tennyson: “To be a Romantic with a capital R in 1986… is deliberately to cultivate a sensibility whose time you know perfectly well has passed.”

I know this is sexist. You know this is sexist. Robert Christgau, who pauses in the middle of every third review to remind us how feminist he is, knows it is sexist, which is why he plays games with the reader, trying to provide plausible deniability. The best example is probably his contemptuous review of Tori Amos’ Little Earthquakes, which I will, again, print in full:

She's been raped, and she wrote a great song about it: the quietly insane "Me and a Gun." It's easily the most gripping piece of music here, and it's a cappella. This means she's not Kate Bush. And though I'm sure she's her own person and all, Kate Bush she'd settle for.

This is what pick-up artists refer to as “negging” — dropping the occasional nice-sounding adjective on top of an insult, so that the target will get the idea that his approval is within reach, and work harder to prove herself. It’s disgusting psycho shit, in other words, and anyone who’s been exposed to enough of it — which is most women over the age of 30 — can see it coming from a mile away. Drop the word “great,” from that first sentence, and maybe “quietly,” and you have what he actually means: She’s been raped, and she wrote a song about it, which is crazy. That sentence is virulently misogynistic, by any standard, and since committing it to paper, Christgau has not reviewed any of Amos’ work.

To be clear: The problem is not (just) that he wrote bad reviews of good artists, or that he ignored artists that I consider important. It’s that even when he “liked” a woman, he cast her as a sexualized object designed for his consumption. A (positive!) review of Bjork’s Vespertine turns into an extended and graphic fantasy about Bjork’s sex life. PJ Harvey’s epochal Rid Of Me is greeted with Christgau’s assessment that “she wants that cock.” I will leave it to you to guess how many times the words “boner” and “orgasm” appear on the Kate Bush page, or to diagnose the mysterious reason that Christgau stopped reviewing her after she turned 35.

Christgau was laid off from the Village Voice in 2008, along with many other writers, but as I recall, his real cancellation came in 2014, when he released a review of a Tune-Yards album that was mostly an extended fat joke about singer Merrill Garbus. Outcry ensued, past writing was raked up, and Christgau retreated from paid writing to the wilds of Substack, where men like him go when no-one can ignore the problem any longer. By that point, though, Christgau had been getting paid to write with his dick for nearly forty-five years, doing irreparable damage to generations of rising artists. Decades after calling Poly Styrene a “plump” “mulatto,” he dismissed the Yeah Yeah Yeahs’ Show Your Bones with a single line aimed at Karen O: “I still don't wish she was my girlfriend.”

Flawed as it was, the poptimist movement was a corrective to something — to a status quo, spanning from the Summer of Love right up until the late 2010s, in which any woman who made music, no matter how talented she was, could not be deemed “serious” or “important” until some self-important white guy two or three times her age decided that he wanted to stick his dick in her. That status quo was real, and horrible; it damaged countless women’s careers, and ended others before they ever began.

I’m focusing on gender, not race, because I don't think I have the expertise to cover that as it deserves, but I have to imagine (cf. Styrene) that tracking the racial politics of Christgau — or his similarly white peers — would be quite a journey. In either case, the idea of the critic-as-gatekeeper was always fatally flawed because of who got to keep the gates — mostly white men, the same people who controlled power and legitimacy and access in every other part of the world.

But I am still not convinced that Taylor Swift belongs in Pitchfork. I still do not believe that the only way to resist “gatekeeping” — or, to give the demon its true name, patriarchy and racism — is to become an uncritical booster of global mega-brands that exist first and foremost to generate revenue. Those brands do not need our help, and they are already doing all they can to control the narrative. Which brings me, at last, to my one and only interaction with Taylor Swift. Or, really, with her team.

The year was 2017. I, notable non-woman Jude Doyle, was working at a “women’s magazine,” covering “women’s issues,” because of what my face and body looked like. Naturally, in this position, I was called upon to cover the most important women’s issue of this or any other time: The new Taylor Swift album, Reputation.

Specifically, I was asked to write about the controversy surrounding the album’s release. Swift had made a big and public deal out of being offended by the latest Kanye West single, “Famous,” which had a cringey verse about how he made her famous by crashing the stage at the 2008 VMAs and “might still have sex” with her. He claimed that he’d run the lyrics past her and gotten approval before the song’s release; she denied it through her publicist, who issued the following statement:

“Kanye did not call for approval, but to ask Taylor to release his single 'Famous' on her Twitter account. She declined and cautioned him about releasing a song with such a strong misogynistic message. Taylor was never made aware of the actual lyric 'I made that bitch famous.'”

West’s wife, Kim Kardashian, released a video of West on the phone with Swift, in which he read the lyrics aloud to her for approval, and she gave it. No caution about “misogyny” was ever uttered — her one stated hesitation was that she was too close to being “overexposed,” press-wise — and her permission is clearly stated. The final line, “I made that bitch famous,” is not read aloud by West, but the rest of the verse is. This is going to be important later.

Well: The Internet found Swift’s actions to be deeply racist, which — since she had cast a Black man as a scary, threatening, sexually inappropriate misogynist over something to which she had in fact given clear verbal consent — is understandable. The fact that Taylor Swift had an avid fan base among online Nazis and white supremacists came up as further evidence against her. It absolutely did not help that Reputation was the album on which this particular white girl decided to try rapping. The controversy has faded considerably in past years, mostly due to the fact that, well, Kanye West is a Nazi now, and no-one feels like defending him. At the time, though, it was huge; a woman who’d built her brand on truth-telling being caught in a lie, in a way that cast doubt on her entire public persona. Many observers confidently predicted that her career was over.

I didn’t want to write a piece slamming Swift — I’d already done that a lot, and it was starting to feel mean-spirited, especially now that everyone else was piling on. So I wrote a piece about the predictable life cycle of a pop star, and how we build women up only to tear them down, and how depressing all that is. I won’t claim it was a brilliant piece, but it was a sympathetic one, enough so that the reaction on social media was mostly outrage that I would dare to defend her.

Then Taylor Swift’s team called my workplace. They, too, were outraged — but for an entirely different reason. I had done two things in that piece that could not, under any circumstances, be forgiven: I had mentioned the Nazi fan base, which Team Taylor did not want mentioned. I had used the word “lie” to describe Swift’s actions in re: the tape, and the words “lie” and “Taylor Swift” should never be uttered together. This was a big fuck-up for my bosses, very very big, and it was so big that Taylor was willing to withhold future interview access unless somebody went in and “corrected” (that is to say: censored) the published article.

Now: Take a look at that statement again.

“Kanye did not call for approval, but to ask Taylor to release his single 'Famous' on her Twitter account. She declined and cautioned him about releasing a song with such a strong misogynistic message. Taylor was never made aware of the actual lyric 'I made that bitch famous.'”

A reasonable person, reading that statement, would conclude that Swift was unaware of the lyrics to “Famous” and did not give consent for its release – many reasonable people did read that statement, and they all held that conclusion until the video surfaced. Both claims are untrue: She was aware. She gave consent. The statement says that Swift objected to the song’s release on the grounds of its misogyny; in the taped conversation, she does not object to its release, and her hesitations are about how it will affect her press. You can call it a lie of omission, if you like, since the statement is carefully constructed to tap-dance around which lyrics Swift heard and which she didn’t, or because she let her publicist issue a statement rather than making one. But it is a purposeful misrepresentation of the truth, and the word we use, when someone purposefully misrepresents the truth, is lie.

In my recollection, the word “lie” was removed from that article. The changes were made as Swift and/or her people demanded. I have to rely on my recollection, because as of right now, the article has seemingly been removed from the site. I was getting harassed by Swifties over it as recently as this summer, but it doesn’t show up when you Google, and if you follow a surviving link to it (in a piece that calls it “truly remarkable;” thanks, PopMatters!) you wind up on a timeline of Taylor Swift’s relationship with Travis Kelce.

I will re-state: Reputation was arguably the lowest ebb of Swift’s popularity and clout since 2008. Even at that low ebb, she had enough power to essentially dictate what journalists were allowed to write about her, and to strong-arm particular journalists and publications who did not fall in line. I won’t pretend that this sort of thing doesn’t happen, but it is considered extremely unethical. How unethical? In my nearly two decades of writing, I’ve encountered it in exactly two contexts:

1) Male celebrities threatening to revoke access to themselves or their fellow celebrities in order to keep a magazine from covering #MeToo allegations.

2) Taylor Swift, prohibiting the publication of any article that does not portray her as America’s Most Special Goodest Girl Who Has Never Done Anything Wrong.

The proper role of a music journalist — or any journalist — is always adversarial, not in the sense of being needlessly mean or hostile, but in the sense that it is our job to publish the truth, whether or not our subjects like it. A journalist is not a fan; a journalist is not a friend; a journalist is someone who says what happened. That role is badly compromised by the rules of celebrity access journalism, in which the fate of your publication may depend on the ability to run a profile of so-and-so, and your ability to get that interview depends on never publishing anything that pisses so-and-so off.

Poptimism failed, not because of its commitment to social justice – which was a good thing – but because it had no material analysis. It cast pop stars as underdogs, outsiders, underestimated and dismissed by the Rockist Establishment, without pausing to recognize that they were vastly more powerful than any critic ever would be. Freelancers making $150 per review were going to the mat to defend millionaires who did not care about them, and who in fact viewed those freelancers as an obstacle to their own complete narrative control. If they could have eliminated every single one of our jobs and replaced us with a machine that printed press releases, they would have, and I actually had a gig writing press releases for record labels, at one point, so I know this to be true.

An already written opinion article had to be changed to suit a subject’s preferred narrative, and then, somehow, it wound up disappearing altogether, and you and I sit here wondering about whether Taylor Swift, or other pop stars like her, are being covered fairly. They do not want to be covered fairly. They want to be covered the way they want to be covered, and they find ways of getting that done.

Taylor Swift did agree to grace the cover of that women’s magazine, in case you wondered. It was two years later, in 2019, with an article she’d “written” accompanying it. Her article, unlike mine, is still online.

My point here is not to call Taylor Swift a bad person. I don’t think anyone can become a billionaire while being a good person. The demands of decency and the demands of relentless accumulation are too radically opposed.

So are the demands of being a Swift-level megastar and those of being an artist. I have written a lot of dumb, bad stuff about poptimism by pretending that I can think like a music critic — I am not a music critic. I’m a feminist writer, predominantly, or a “writer about gender,” and “cultural critic” sometimes comes into the job description.

But I do have the conviction, naive though it might be, that art exists to shed new light on the human condition — and that music, in particular, exists to give voice to the kinds of emotions that are too raw and powerful to be merely spoken. I think music is usually best when it is made by people who are fundamentally at odds with the dominant culture; because of race or gender or sexuality, sure, but also just because they’re weird, because they see the world differently than most people and have something new to say. I think art in general, and music particularly, is the closest you can get to opening up your heart like a locked cabinet and showing someone else what’s in there. I think that art is, and should remain, a place for the world’s rejects and outcasts and weirdos to be at home.

Also on Spotify, if you don't mind missing the Joanna Newsom song. (You should.)

Look again at that list of artists Christgau dissed. When I listen to those songs, I hear women who are angry, crude, funny, messy, horny, gross, scary, queer, vulnerable, melodramatic, excessive, confrontational, imaginative, ambitious, literate, political — women who are everything the culture tells women not to be, who break and remake the category of “woman” in their own image every time they perform.

Those qualities are exactly what I’m missing when I listen to a Taylor Swift album. Her sound since 2020 has been a vague, ignorable haze of almost-melodies; her sound before 2020 was Max Martin dancing on the grave of Loretta Lynn. I understand that the beigeness of her persona is intentional, meant to ensure maximum relatability: Girl squads, cats, Momofuku birthday cake, matte red lipstick and winged eyeliner, Hashtag Millennial adulting while being adorkable, so so so so so many songs about needing boys to like her. But after a lifetime of being told that art was a place — perhaps the only place — where the world’s freaks and queers and indoor kids ruled the roost, seeing a woman use music to express the sentiment “I am the most normal woman to have ever normaled” feels like a spiritual violation. It feels like this comic in music form.

The “aw, shucks, I’m just a nice, polite, ordinary girl who wants a boyfriend” schtick is disingenuous — this woman has not lived anything resembling a “normal” life since the second Bush administration. It’s also insidious: “Nice, polite, ordinary girl who wants a boyfriend” is an ideal constructed by the patriarchy, intended to make girls miserable, turn them against themselves, and in some cases kill them. I get that some people find Swift’s corporate bent appealing, and see the slick construction of her persona and the way she wields it to climb the ladder as inspirational — woman in a man’s world, and all that — and I’ve been called a neoliberal girlboss feminist often enough that I won’t fling the accusation around. Still, there’s something creepy about it: A woman who’s built a billion-dollar business empire by telling little girls that the love of a good man is all she needs.

But it is not Taylor Swift’s job to liberate girls from patriarchy. It is not even her job to make music. It is her job to appeal to the largest possible number of people, so that she can make the biggest possible heap of money, and that job necessitates playing along with the demands of a patriarchal culture.

“Taylor Swift,” as you and I experience her, is not a person, but a billion-dollar corporation; the songs are not ends in themselves, they are content, dropped at regular intervals, to generate a new round of merchandising and licensing opportunities. That corporation is highly profitable, and working under an obligation to protect its bottom line; as such, it cannot take risks. Taylor Swift cannot self-express, she cannot innovate, she cannot stretch the limits of the form – she cannot do anything that a capital-A Artist might need or want to do – because that interferes with her job, which is to be universally likable, or at least inoffensive, and thereby attract the broadest possible base of consumers.

So, does Taylor Swift need to be reviewed in Pitchfork? I refer you to the appropriate Mad Men meme, which I should probably stop posting now that I know how problematic Matt Weiner is:

You cannot apply the standards of art to something that was never intended to meet those standards. Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s — in this case, a private jet and an engagement ring the size of a cargo freighter — but render unto God what is God’s.

A proper poptimist will tell you that there is no God, and no such thing as “authenticity,” either. We’re all selling ourselves, and we are all some kind of fake, so what’s the harm of rewarding the people who are best at selling and faking?

But that argument isn’t sophisticated; it’s cynical. It leads, not to democracy, or diversity, but to the graveyard of AI, where human-created “art” is overtaken by cheaper, slicker machine-based imitations. Swift often seems to me like what you’d get if you typed “female singer-songwriter empowering” into a generator, a collection of signifiers and tropes and slightly blurred imitations of styles formerly invented and perfected by real human craftspeople. But there is a level of inauthenticity beyond her, and that’s where we’re heading. If all that matters is what sells, if authenticity is always an illusion, then it shouldn’t matter if there’s a real human being making the music, or any real human beings evaluating it. A machine can do Taylor Swift’s job, and a press release can do yours.

So I’ll cling to “authenticity” for the time being. It is, after all, the quality we once called soul. It’s the lyric clarity of Joanna Newsom describing human life as “joy landlocked in bodies that don’t keep;” it’s the viciously funny portrait of a male feminist’s failed attempts to bridge the Orgasm Gap in “Come Again;” it’s Tori Amos describing the experience of being a nice, normal polite girl who wants a boyfriend as a spiritual torture roughly on par with Guantanamo, which — in my limited and non-standard experience — it was. It’s the rumbling bass of the piano on “Criminal,” the vertiginous whoosh as the strings take off on “Isobel,” the competing portraits of gender dysphoria in PJ Harvey’s “Man-Size” and Anohni’s “For Today I Am A Boy;” it’s Poly Styrene’s voice tearing in half as she hollers “OH BONDAGE! NO MORE!!!!”

It’s all the times when the music cracks open and something shining and huge and true falls out, some feeling too powerful for words alone. In those moments, music does what it was made for — it lets us put our own weird, unique, messy, unprecedented human hearts into each other’s hands, and proves that our oppressors, for all their power, cannot shut us up or limit who we are.