On Seeing "Eddington" In Trump Country

Jude Is Afraid.

Welcome back to the newsletter! The takes are hot this week. But first, book announcements.

Be Not Afraid #2, the second issue of my horror comic series with Lisandro Estherren, is on stands now. Pick it up at your local comic shop now so you can be all caught up when Issue #3 comes out on 8/27.

My non-fiction book DILF: Did I Leave Feminism is due out October 14, and is available for pre-order anywhere you buy books. If you're in NYC on October 14, I'll be in Astoria – the neighborhood where I lived for more than a decade, and which I left exactly 5 minutes before it became trendy – for a conversation with the amazing Heather Hogan. Get tickets and learn more here.

This newsletter contains detailed plot discussion of "Eddington," including its ending. It's still in theaters, so if you want to avoid being spoiled, you can opt out now.

Last week, my husband and I drove out to a nearby town to see Ari Aster's Eddington.

I’m not going to tell you which town. I try to be relatively vague about where I live — there are a lot of weirdos out there, and I don’t want my family exposed to their attention. It’s upstate New York, though, and not polite “upstate,” the kind that is essentially a suburb of New York City; it’s up upstate. The kind where you have to drive between towns because yours might not have a movie theater. The kind where you’re always ten minutes away from a cow pasture. The kind where politics shift, very rapidly, between the small liberal-arts university towns where it’s safe to be gay — the kind where I can live, as A Transgender — and the rest of the small towns. The ones that ensure this area always goes Republican, straight down the line, in every election. The ones where Donald Trump won the 2024 election by around 70 percent.

The movie theater where my husband and I saw Eddington was in one of those small towns, in a decaying strip mall with half its shops missing. We drove in behind a van whose rear window decal read “TRUMP LIFE,” in cheery Live-Laugh-Love cursive, like Wine O’Clock for concentration camps. Here is the first sign that something was wrong: The theater was packed.

I should explain: This is a tiny movie theater. It only has about thirty seats, and they’re all recliners; you might as well be sitting in someone’s living room. Despite how tiny it is, I have never seen it full, for anything, least of all an A24 film — when we saw The Substance in this same theater, my husband and I were the only people in the room.

This time, though? For this movie? It was a full house. Eddington isn’t doing particularly well anywhere — last I heard, it had made back only $10 million of its $50 million budget, a worse showing than Beau Is Not Afraid — but it was doing great in this one strip-mall theater in a heavily Republican small town that lives the Trump Life. Nor was the audience stereotypically A24-art-movie types. They were all white — which isn’t surprising in that area of the country — but they were also mostly older people, by which I mean older than me, in their fifties or sixties.

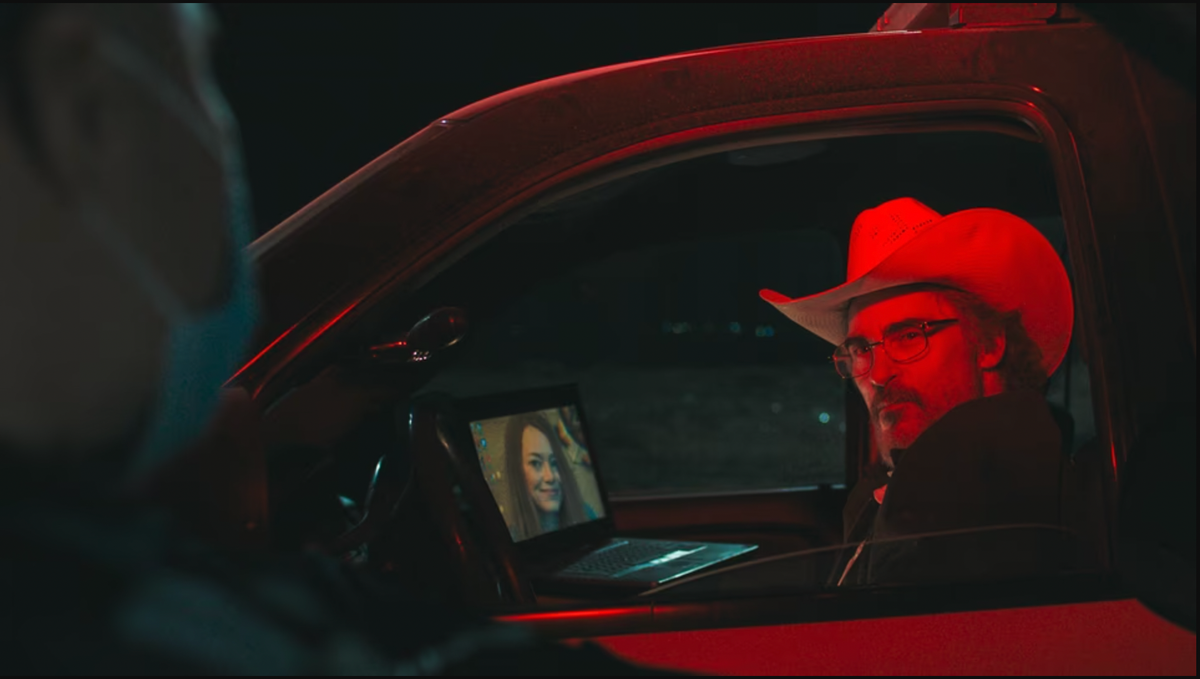

And all of those people were there to see Eddington, which turns out to be a surprisingly sympathetic portrait of a small-town sheriff (“Joe,” played by Joaquin Phoenix) who starts by hating COVID-era mask mandates and descends into a MAGA rabbit hole that ends with him declaring war against “Antifa terrorists.” And somewhere in the middle of the movie, when I heard which jokes they were laughing at and which they weren’t, all of those disparate little pieces clicked into place, and I knew.

I knew why all the old white people in the Republican small town were coming out to see Eddington. And I was terrified. Because at the end of that movie, when the credits rolled, I was going to have to stand up and walk out of that theater, and they were going to see me. Every single one of them.

I do not think Ari Aster made Eddington as a piece of Republican blood pornography. I should say that up front. I think he meant Eddington to portray an America that is increasingly fractured and polarized, picked over by grifters and conspiracy theorists, so that even people who live in the same small town are essentially occupying different realities. Everyone in this movie is being drawn to a different conspiracy theory or variety of political extremism, whether it be MAGA, or QAnon, or (here’s where it starts to unravel) Black Lives Matter. Everyone looks crazy to everyone else, because they’re all drawing their information from different sources, so they can’t agree on the most basic facts. When two people from different realities meet, they can’t hold conversations; all they can do is scream, and each person’s screaming sounds like impenetrable lunacy to the other, so it only makes matters worse.

I think that Ari Aster believes it is essential to understand Joe’s perspective, and his journey toward fascism, because most of his audience (which is presumed to be young, which is presumed to be educated, which is presumed to be middle- or upper-class, which is presumed to be progressive or leftist) will already understand the Black Lives Matter protesters. Joe is the figure most representative of where we are headed as a country; his sickness is America’s sickness, and we need a diagnosis in order to find a cure.

Accordingly, the movie shows us the world as Joe sees it, and Joe as he sees himself: The nicest imaginable guy, soft and kind and decent and routinely downtrodden by liberal elites and know-it-alls who are laughing at him behind his back and sometimes to his face. Joe’s first political awakening comes when he sees an older white man getting kicked out of a grocery store for not wearing a mask. “You can’t treat people like that,” he says, and he buys the man’s groceries. This is how he sees himself: As a crusader for neighborliness, kindness, decency, respect for the elderly, basic small-town values.

When the world erupts into riots over police violence and institutional racism — this is May of 2020 — Joe cannot for the life of him figure out why anyone would be mad at him, the nicest man in the entire world, just because he’s the sheriff. Black Lives Matter comes into his life like a catastrophe, a grenade thrown through a window onto his dinner table, while he’s just trying to have a nice family meal. Joe looks at footage of riots and police stations being set on fire, and he sees that the world is going sideways, becoming inexplicably violent somehow, and that he’s got to toughen up in order to meet its force.

Fully the second half of this movie is Joe systematically killing minorities and abusing his power as a police officer to escape the consequences. I’m telling you now, because I don’t think Joe is intended to be a hero. We are meant to watch him slowly slide from helplessness to fear to anger to hate, to become the worst possible stereotype of a crazy racist MAGA sheriff, without realizing what is happening to him, because that is also what happened to the United States — slowly, then all at once, we became a fascist country.

If it helps, I will tell you that I even think Joaquin Phoenix — the most viscerally unlikable actor in cinema, whose on-screen presence I normally cannot abide — does an excellent job at playing Joe, letting you track his disintegration across the course of the narrative. There’s a moment in the movie, when Joe is driving away from a forbidden COVID party thrown by the snooty Democratic elite mayor (played by Pedro Pascal), where something in Joe’s eyes goes hard and dead, and you think “oh, he’s an actual Nazi now.” Which he is. It’s a total and permanent soul death that is conveyed, unmistakably, just by Joaquin Phoenix twitching his eye muscles a little. Good job, Joaquin.

If I had watched Eddington alone, in my living room, I probably would have loved it. If I had watched it at the Alamo Drafthouse in Brooklyn, surrounded by my fellow coastal elites, I might have had a great time. But watching it in that tiny, crowded theater in Trump country — well aware that I was probably the only trans person in the room, that I’m one half of a gay couple, that my husband is probably the only non-white guy in the room, that my hair has been growing out and so I’m starting to get weird looks and “is that a boy or a girl” questions from children more often — all I can tell you is that it felt really, really important to me to know why all those old white people were watching Eddington.

Because if even a tiny portion of the audience doesn’t get the joke, then Ari Aster just made an action movie where the Joker fights antifa super-soldiers with a machine gun because woke Democrats won’t let him preserve his personal liberties. And releasing that movie, at this particular moment in time, adds fuel to a fire that will burn all our lives to the ground.

“I think it’s just talking about how life is these days,” said my husband, who really liked Eddington. “Like: There’s this guy who just walked into a building in Manhattan and shot a bunch of people, right? And I was getting texts like, ‘no-one knows why he did it yet, but it’s right near United Health. Blackstone’s down there. All sorts of companies are down there.’ The implication being that this guy was doing a Luigi, shot somebody to fight capitalism. But it turned out that there’s also an NFL headquarters down there, and this guy got concussive brain disease playing football. So he was trying to kill the NFL guys. But he took the wrong elevator and shot a bunch of people who had nothing to do with it.”

He took a breath.

“I think people just kill each other whenever they want to make a point now,” my husband said. “I know you’re really against that, and I’m sorry. But Ari Aster isn’t making that happen. He’s just showing you what life is like.”

I think this is also a perfectly fine take on Eddington. I don’t expect mine to be the definitive reaction to the movie, and it isn’t even really a review of the movie — it’s a review of the experience of watching this movie surrounded by my fellow human beings, who scare the shit out of me half the time. On some level, I worry that I may be blaming Aster for his own success – I watched a film that wanted to scare me about the direction America is headed, and I walked away from it scared of Americans. That's not a flaw.

Like any he/they bleeding-heart feminist liberal arts graduate worth his/their salt, my instinct is to turn the blame inward and start interrogating myself: Did I actually know all the people in that theater were horrible transphobic MAGA racists? Isn’t that just me, and my relatively privileged perspective, refusing to engage with people whose lifestyle is different from my own? Have I never written a satire or a joke that landed sideways? Don’t I know how delicate these things are, and how much they rely on context? Am I saying rural white people are stupid, that they’re too stupid to get satire, and isn’t that kind of the attitude that is making so many of them spin out, as portrayed in the movie Eddington? Am I the problem?

No. I really don’t think I am. I’m undeniably paranoid, but that is how trans people in conservative rural settings survive — by being paranoid, by never underestimating the sheer amount of hate that lies in the hearts of many people around them.

Traditionally, a lot of queer discourse is generated from within progressive coastal cities, because that’s what queers have always done: We congregate together, for safety, in cities which then start to reflect our presence and culture. I don’t question that strategy, or deny anyone’s right to it. But there are lots of us who don’t live that way, or can’t live that way, and we live much closer-up to the MAGA phenomenon than you might expect.

Like: A few months ago, my kid came home complaining that one of the teachers at her school wasn’t “fair” to her. I did the thing you’re supposed to do, tell my kid that dealing with difficult people is part of life and that she needs to learn to coexist, but then my husband showed me pictures of the teacher’s car. It was not only covered in a tribal tattoo pattern — I was not even aware that it was possible to cover one’s entire car in a tribal tattoo pattern, but this lady managed it — it had several large “TRUMP 2024” stickers on the back, in the shape of the Punisher skull, which is what they use when they really intend the racism.

Oh, I thought. That’s what “not fair” means. My kid, one of the vanishingly few non-white students in that class, is having a “problem” with Miss Punisher Skull Trump Logo. Okay.

I mean, what can you say? People are allowed to cover their cars in white supremacist regalia and then drive them to the school where they teach your children. We may be living in different realities, but her reality impacts mine every day.

Which is to say: I think Ari Aster wants his audience to understand Joe, to see how he sees the world — but he assumes we don’t already understand that guy. Many of us do. We were raised by Joe. We grew up with Joe. We live next to Joe. We deal with him, or with Mrs. Joe, on a daily basis. Everyone in that situation has had to develop a working “understanding” of Joe, or at least an understanding of the threat Joe poses, in order to survive our interactions with him.

And if you know Joe, you know that he’s not actually “working-class” or downtrodden. That’s just the story he tells himself to justify what he’s doing. Many of the capitol rioters on January 6 were comfortably middle-class or upper-class. Trump’s support is strongest among wealthy white men. If Miss Punisher Skull were actually being oppressed and silenced by liberal elites, then she wouldn’t be given a position of unsupervised access to their children. Joe is not being marginalized; he occupies one of the most powerful identities in America, and his beliefs and politics play a disproportionately large part in shaping the country.

That’s why it’s irritating that so much of Eddington plays like a glorified South Park episode about how “both sides” are wrong and crazy, or that Eddington’s political message boils down to a decade-old New York Times op-ed about “economic anxiety,” essentially arguing that young leftists are being led astray by (sigh) identity politics, and Black Lives Matter specifically, and thereby missing Joe’s very important class-based struggles.

That’s why it matters that all of the Black Lives Matter activists in Eddington, including the non-white ones, are shallow and performative and hypocritical — the searing revelation that teenagers can be kind of annoying has rarely been delivered with more force than it is here — and that the only person of color given any real interiority is a Black cop who is One Of The Good Ones. That’s why it matters that the main Black Lives Matter advocate is a white girl scheming to make her Black ex-boyfriend, the cop, pay attention to her. That’s why it matters that, in a movie that is at least somewhat about the #MeToo era, all of the rape allegations that are leveled in public turn out to be false. (There is one true allegation — Joe’s wife was very obviously abused by her father — but it is never actually spoken aloud.) That’s why it suddenly matters that, in Ari Aster’s last movie, there was also a gaggle of teenage girls who flung false rape allegations around to get their way, and that this, along with Wicked Devouring Mothers, is starting to be kind of a theme for him.

That’s why it matters that, at the end of Eddington, we find out that there are literal antifa super-soldiers, who are merciless homicidal maniacs, which — while very funny, if you view this as the shadowy hand of Capital moving to reinforce Joe’s delusions; he’s acting out the bizarre action movie your weird Republican uncle thinks he lives in — also winds up retroactively confirming all Joe’s beliefs and potentially justifying him to a more literal-minded viewer.

And there is always a more literal-minded viewer. That’s the thing. The Matrix was a trans allegory directed by two women, and it wound up generating the key metaphor of the Men’s Rights movement. You can understand where the confusion got introduced there — the vagaries of the closet meant that no-one, maybe not even the Wachowskis themselves, could be one hundred percent clear on what they were saying — but in Eddington, it almost seems to get introduced on purpose. This, in a movie about how easy it is for popular media to mislead people or feed into their delusions, and how disastrous the consequences often are.

I know, I know, it’s satire, media literacy, yadda yadda. But that’s the whole problem: I think movies like this rely on you and me to sit here, patting each other on the back about how smart we are, and assuring each other that they’re obviously satire, and that you’d have to be stupid to miss the point. But guess who’s really stupid? Joe is. You know who notoriously lacks media literacy? People who put fucking Punisher skulls on their cars; people who think the Joker is a role model and Fight Club is a heterosexual dating manual and Superman is too woke because it’s about immigrants now. Fascists are dumb, and when a dumb person watches a movie, they get a dumb take-away, and to those people, Eddington is probably an artsy Falling Down remake about how woke elites pushed a nice guy like Joe to the brink and made him shoot people, and they’re not about to let some liberal-arts-college educated transsexual with a minor in Women’s Studies and a film blog tell them otherwise.

Who’s really condescending to small-town rural white folks here? Me, the small-town rural white guy who’s concerned about potential messaging misfires in Eddington? Or the guy who made a whole movie about how no-one takes Joe seriously, but didn’t realize that Joe also goes to the movies, and that he would show up?

So we drove back, to the safer, more expensive kind of small town, where Pride flags hang off the adorable knick-knack shops, and the “TRUMP LIFE” stickers are replaced by “BERNIE 2020,” and I can pretend to live in the country without facing any of the risks that entails.

I don’t think Eddington is wrong about me, or about the privilege I exercise; I can retreat into my beautiful life, in the middle of this burning country, and refuse to see any of the chaos until it drives up in an SUV covered in a Blue Lives Matter-specific Godsmack logo and starts exercising power over my kid. I think Eddington is right about a lot of things, actually; no other movie has so effectively captured the feeling that everyone is slowly going some kind of nuts, that we’ve snapped the tether connecting us to reality or common sense and are now just hurtling off into the void. I even think I get the point of the Black Lives Matter scenes, which (at their best) are less about vilifying protesters and more about how startling and alien protest jargon sounds to people who aren’t used to it: You think you’re the only one talking about brainworms? From these people’s perspective, you kids sound crazy.

But I was worried about getting out of that theater in one piece, and I don’t think I was wrong. I think that if you’d been in that position, you too would suddenly find it immensely important to know which jokes those old white people were actually laughing at and why. If Eddington has a claim to being Great Art, it’s because of how it crystallized that truth: I am terrified of my fellow Americans. I might try to push that feeling down, or disguise it as something safer, like anger or mean jokes about their cars, but the fact is that I do not feel safe. Everyone is losing their minds right now, half of these people are goddamned maniacs, God knows how many of them are armed already, and there is certain, quickly growing class of maniac whose delusions revolve entirely around trans people being a cosmic threat.

I don’t think it’s “extreme” for me to want to be left alone as I walk out of a movie theater and into the parking lot, and I don’t think “both sides” feel that way, either. I don’t think Black Lives Matter is primarily a vehicle for white people to be performatively righteous, even though it gets used that way — I think a bunch of Black people were getting murdered, and other Black people wanted to not get murdered. I don’t think “both sides” are equally radicalized or equally out of touch there. I don’t think there’s anything radical about wanting to live.

Eddington is a good satire, sometimes a great one. But we’re pretty far gone down the rabbit hole, and I don’t think a well-crafted satire is going to save us. It might make things worse, though. Anything can. Anything might. Everything we’ve tried has.

Eddington is still in theaters. If you want to watch a movie about a working-class rural white guy dealing with economic stress and a mental health crisis, there's a really wonderful movie called Take Shelter on Hulu that I think you would like.

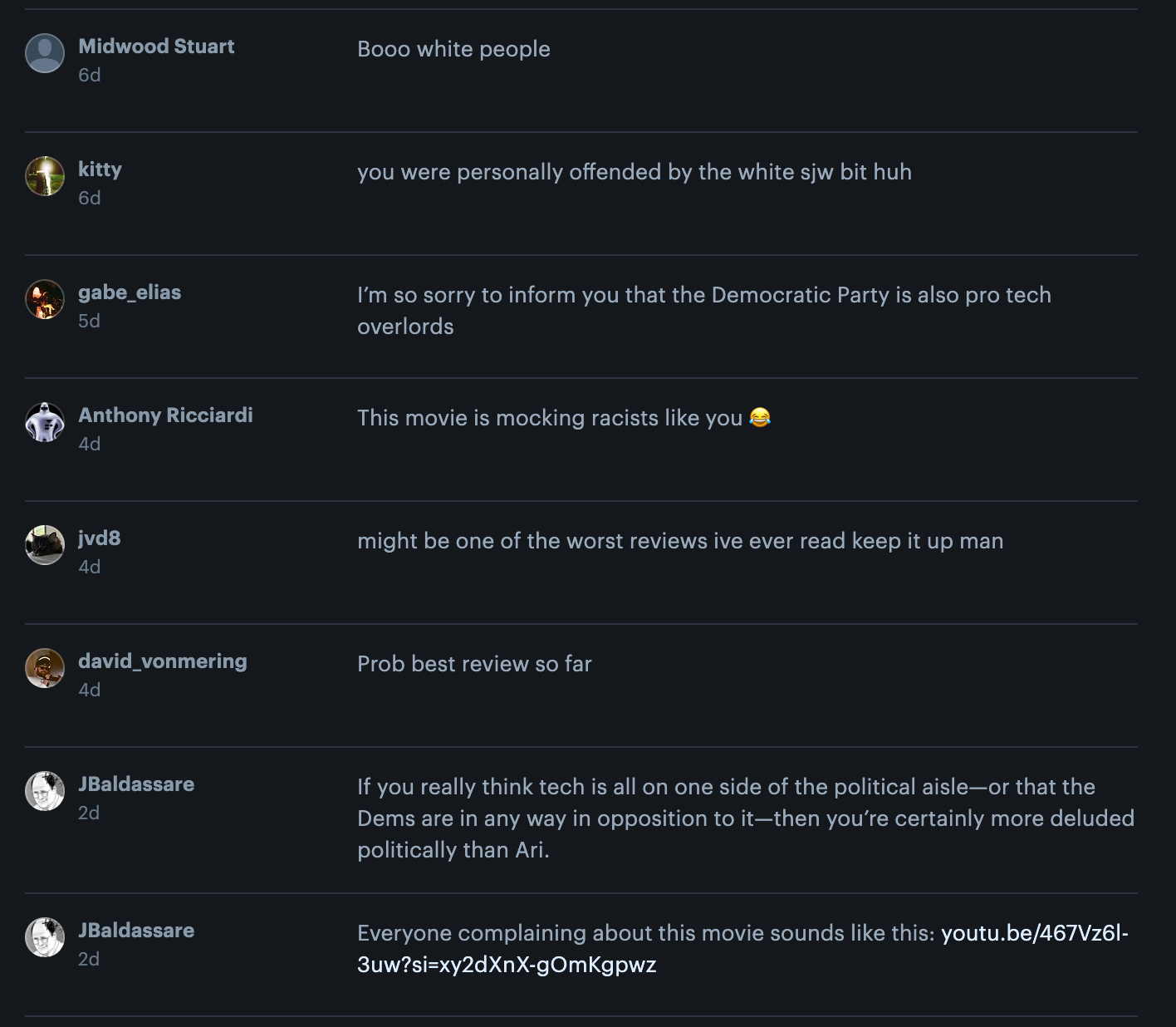

The joke I LOL'd hardest at was when a white male protester said that, as a white man, he shouldn't be speaking, he should just be listening – "AND I WILL, AS SOON AS I FINISH THIS SPEECH!!!!"