Finally, I remember where the portals come from.

When I rewatched Being John Malkovich, last fall, I remembered what seemed like a bizarrely specific fantasy. I was convinced, in my late teens, that science would invent a way to have the experience of being in someone else’s body. Physical sensations are just information being processed by the brain, and there has to be some way to encode, for example, everything my brain is doing right now as I sit at my laptop and type this sentence. There’s got to be some way to record and replay the experience of being me in this moment, pressing these keys, fixing a punctuation mistake, leaning to the left as I hit “delete” on an irrelevant clause.

I remember having this fantasy often. I put a lot of nerdy adolescent energy into it. Yet I don’t usually fantasize about technology, and this was such a distinctively sci-fi premise that I assumed I’d gotten it from somewhere: William Gibson, or some half-forgotten Star Trek episode, or maybe Lawnmower Man. It was only when I decided to watch a bunch of Kathryn Bigelow movies that the rest of the memory surfaced. The technology I was obsessed with as a teenager is the premise of her 1995 cyberpunk epic Strange Days. Twenty-five years later, the brain-transfer technology is the only part of Strange Days that hasn’t come true.

Strange Days is the biggest flop of Kathryn Bigelow’s career. It ruined her reputation for a decade. It has gone in and out of availability many times, and is not currently available to rent or buy or stream. It is probably her best work.

Feminists sometimes dismiss Bigelow as “one of the boys,” but she has never had a boy's margin for error. Hand Bigelow any traditionally masculine genre — the Western, the action movie, the war movie — and she will provide you a tight, expertly crafted take. Yet the most masculine genre of all, the bloated, expensive, immersive, I-designed-a-new-camera-specifically-for-this-shot statement piece, was denied her. Bigelow was coming off Point Break when she made Strange Days. She’d given the world a perfect action movie; audiences loved it; it has become a classic. Yet give her a two-and-a-half-hour candy-colored cyberpunk noir where Juliette Lewis sings PJ Harvey b-sides in iridescent chain mail, and Angela Bassett wears leather pants and beats the shit out of a white woman with dreadlocks, and the Black Lives Matter movement gets predicted in between queer gender experimentation and tiresome white male divorce feelings, and no-one showed up.

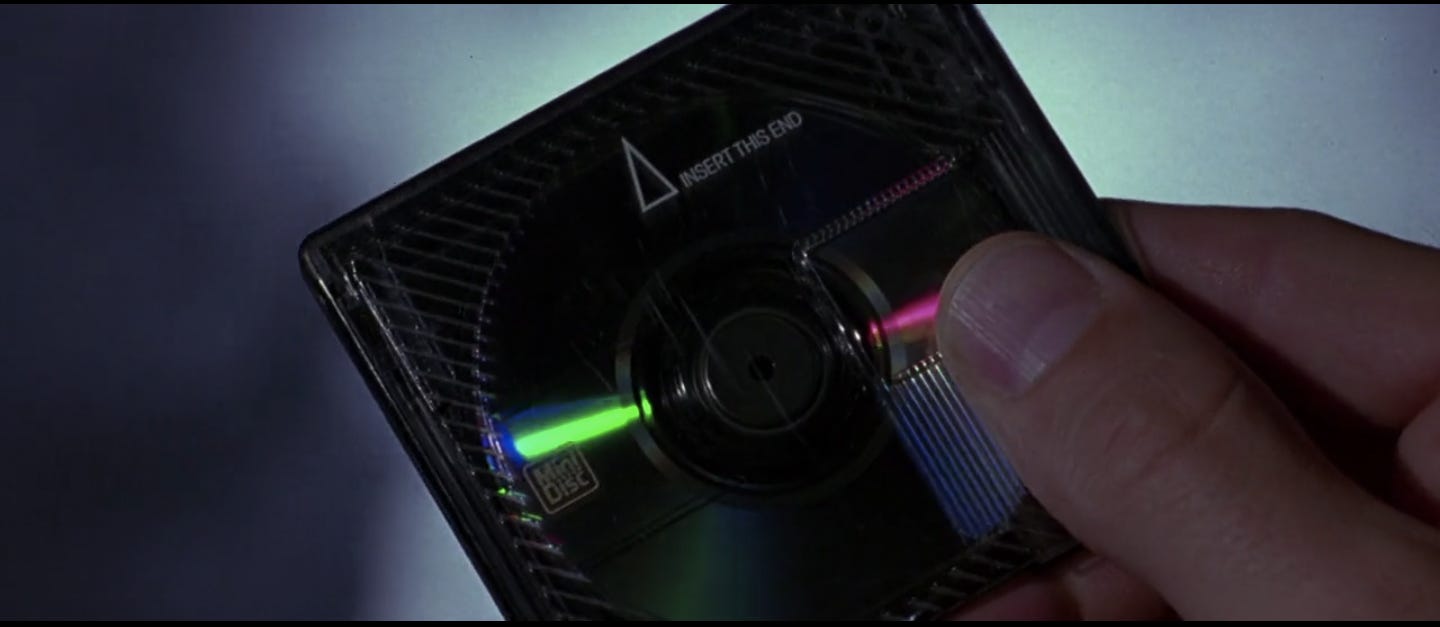

Still: Don’t you want to see that movie? Strange Days failed spectacularly, but only because Bigelow went so hard that she missed the mark and wound up ahead of her time by about twenty-five years. Admittedly, it would help if the movie were not set in the far-away dystopian future of (checks notes) December, 1999. Yet this is where we lay our scene: Lenny (Ralph Fiennes) is a disgraced vice cop who now sells “SQUID recordings,” neural recordings of being in someone else’s body. Most are pornography. Adorably, they look like little CD-Roms.

Lenny also, creepily, keeps lots of recordings of himself fucking his ex-wife (Juliette Lewis), who used to be an innocent slip of a girl Rollerblading in a thong, and has now become a dissolute rock star who sings PJ Harvey b-sides in iridescent chain mail. (I’ve always thought the “I’m the King of the World” line in Titanic was an intentional PJ Harvey reference. My only evidence is this movie. Nothing will dissuade me.) The Kathryn Bigelow Gender Issues Train arrives right on time. Consider, for example, the scene where Lenny explains the SQUID experience to a new customer:

LENNY: It’s about the stuff that you can’t have, right? The forbidden fruit. Like running into a liquor store with a 357 Magnum in your hand. Feeling the adrenaline pumping through your veins.

(CUSTOMER is unconvinced.)

LENNY: Or, you see that guy over there with the drop-dead Filipino girlfriend? Wouldn’t you like to be that guy for twenty minutes? The right twenty minutes? I can make it happen… I can get you what you want. You just have to talk to me. Trust me, I need you to trust me… You say it, you think it, you can have it. You want a girl?

(CUSTOMER remains unconvinced.)

LENNY: You want two girls?

(CUSTOMER becomes even more unconvinced.)

LENNY: I don’t know what your thing is, what you’re curious about. You want a guy?

(CUSTOMER’s lack of conviction increases.)

LENNY: Maybe you want to be a girl. Hey! Think of that. Be a girl. See what that feels like.

Cut to CUSTOMER, mind blown, life changed, as Ralph Fiennes tells them that they just experienced taking a shower as a lady. It’s not just that I got the Being John Malkovich fantasy from this movie. I think Charlie Kaufman might have gotten the Being John Malkovich fantasy from this movie. It’s right there.

Strange Days isn’t an optimistic or utopian movie, and the SQUID is not the Holodeck. Bigelow spends a lot of time here interrogating the moral premises of her own work, specifically her drive to recreate and vicariously enjoy danger. Yes, a first-person experience of a hold-up is thrilling — we know, because Bigelow designed a camera that mimics the human eye just so she could film one — and so is first-person sex. But what about a first-person rape? A first-person murder? We get those, too, and our initial enjoyment of the SQUID premise feels ickier every time.

People need to go to “the dark side of the street,” Lenny protests; “it’s what we are.” It’s certainly what people are in Kathryn Bigelow movies; given access to all of human experience, her heroes gravitate inevitably to the experiences where someone gets hurt. Before long, Lenny gets ahold of two very illicit SQUID recordings: First, a snuff film featuring the rape and murder of a young woman. Second, a recording accidentally made by that young woman, featuring the police execution of rap star Jeriko-One, who had been protesting the racism of the LAPD.

This is when Angela Bassett and her leather pants enter the picture, and here is where the movie goes from being an ambitious-yet-messy work to being astonishing.

Mace (Angela Bassett) is a cop. She is also in unrequited love with Lenny, a man who continually jerks it to sex tapes of his ex-wife and whose body is mostly congealed hair grease. Both facts indicate some serious errors in judgment, yet we can forgive her, because she is the true hero of the movie, and probably the best female lead Kathryn Bigelow has ever written.

Mace is pulled in by Lenny to investigate the snuff film, but when she sees Jeriko-One’s death, that becomes her priority. We also see the footage of Jeriko-One being killed, and it is intensely familiar to us, in ways that it couldn’t have been for an audience in 1995. The camera Bigelow designed for the SQUID scenes — grainy, shaky, twitchy — mimics the human eye, but it also mimics the camera on an iPhone.

Mace believes the tape of Jeriko-One’s murder has to be released. People need to know what is being done in their name. Her white friends tell her otherwise. If she releases the tape, one of them tells her, "it'll spark the biggest riot in the history of the city... As soon as the fire starts, the street cops will start capping off anything that moves. It’ll be an all-out war, and you know it." Mace is undeterred: "Maybe it's time for a war," she says.

Bassett is fantastic here: Enraged, righteous, with biceps that could smite God, punching her way to justice. It's hard to screencap her because she's literally moving too fast to be more than a blur for most of her scenes. Watching Strange Days in 2021, it seems clear this movie should have made Bassett one of the biggest action stars of her generation, the way Point Break took Keanu from indie dreamboat to John Wick, but Bigelow was not the only talent the world wasn’t ready for in 1995.

Strange Days is by no means perfect, politically or otherwise. There’s a Boomerish insistence that police brutality comes down to a few bad apples. There’s a very 1990s emphasis on the goodness and virtue of white people who give a shit. The plot revolves around Jeriko-One's once-in-a-lifetime talent as a rapper, yet Bigelow seems unaware of what rap was supposed to sound like, or maybe I’ve just forgotten what it sounded like in 1995. (Was it meant to be extremely slow spoken-word poetry about America?) The footage of Jeriko-One’s death strikes me as realistic, but might strike a different viewer as unnecessarily traumatizing, and Mace’s plan — essentially subjecting herself to violence so that people can witness her being hurt — requires her to suffer in ways you can easily read as trauma porn.

Yet science fiction is the craft of extrapolating the future from the present, taking the most relevant parts of the current moment and expanding on them to see what the world might be like down the line, and as a piece of science fiction, Strange Days is stunning. Bigelow predicted that, in the near future, everyone would have access to a highly portable technology which allowed them to record and broadcast their experiences to a mass audience; she predicted that this technology would create a boom in sex work, although some creeps would use it to force sexual contact with their exes; she argued that the technology’s social impact would be a mixed bag at best, and that it would empower men’s sadistic impulses toward women, but that it would also provide necessary aid to disabled people, and create new and vital ways to explore one’s gender identity. Finally, Bigelow predicted that the most important thing we would see, thanks to this technology, was raw eyewitness footage of cops summarily executing Black people, and that, when those images became public, they would spark a mass uprising.

For any piece of science fiction to get this much right is impressive. It is unheard of for the prediction to be off by only twenty years. You can clearly see the elements of the early ‘90s that Bigelow was pulling from — the early Internet, the Rodney King case — yet her cyberpunk dystopia, despite its iridescent color scheme and tiny CD-Roms and abundance of men with gloriously long ‘90s hair, is more or less where we live today.

In the quarter-century since Strange Days, Kathryn Bigelow has become a Serious Director. I am, I confess, ambivalent about this. There was a lot of debate over Zero Dark Thirty's politics, but the most important thing I can say about that movie is that it bored me. I haven’t seen Detroit, her movie about a historic race riot, but it wasn’t well-received. Troublingly, Bigelow's Serious Artist period has been marked by chronic mishandling of race and racism – the Boomer liberalism and white-savior instincts of Strange Days have curdled and become more glaring over the years, so that Bigelow is no longer a product of her times, but noticeably behind them.

Big-A Artistry has rendered Bigelow's work dry and earnest, tamped down her prurient impulses, and prurient impulses are what her best work is about. She understands the appeal of the illicit, and what it means that audiences are drawn to seamy, violent, pornographic things. Her most serious statements tend to come disguised as brute animal gratification: Juliette Lewis’s tits are out for roughly 90% of her scenes in Strange Days, yet it’s not a sexist or objectifying movie. It’s a movie about how our uncontrollable need to see titty will doom us all.

Bigelow seems afraid to make another Strange Days. It was her biggest swing, and her biggest failure; it took her from up-and-comer to has-been, and there was no guarantee she would make it back. Yet it’s also her most prescient movie, and her most original, and her coolest movie to look at; it’s got her most compelling hero and best lead performance; it’s the movie where Kathryn Bigelow most clearly interrogates what it means to be who she is, a feminist obsessed with men, a peace-loving liberal who believes we can only feel alive in the face of death. She looks at herself in a clear light, and does not always rule in her own favor. She is sort of like Mace, the woman in a man's world, but she is exactly like Lenny, selling extreme experiences, making a living off other people’s pain.

Bigelow herself has become a historic figure: The Only Woman To Win The Best Director Oscar, for eleven years and counting, the Famous Female Genre Director before "female genre directors" were a cause. Like many trailblazers, she looks old-fashioned compared to the women who've come after her. This is how it goes: The person who opens the door has to watch as everyone walks right past. Strange Days is her best movie, in part, because it's the keenest reminder of a time when things were different; when Bigelow walked ahead, into a future that she was the first to see.

Strange Days isn't available anywhere except for the seamy underbelly of cyberspace.

I wrote this in February, meaning that I did not intend for it to be timely, but it is, because police violence against Black people is a constant. Here's a GoFundMe for the family of Daunte Wright, and a guide to the practical support currently needed by the people of Brooklyn Center.

In other news: I just started a new weekly blog/column/what-have-you over at Medium. Here's the introduction, and here's the first proper post, about what I've learned after several weeks of being interviewed about The Other Newsletter Platform.

No Safety or Surprise: Strange Days (Kathryn Bigelow, 1995)

Hey, cheer up. World's going to end in ten minutes anyway.