MAW #3: This One's Normal

Wendy Weber, what it means to be "just a mom," and the dark undertow of wellness culture.

Here it comes again: The third issue of MAW comes out today, and it is the one where shit hits the fan. It's available in print exclusively at comic shops. Digital copies are available on comiXology, iBooks, Google Play, and Kindle. The cut-off for comic book stores ordering the fourth issue is this Monday, November 22, so you can put in an order today when you pick it up.

This is part of a series of essays on the series and its influences. We're now in the thick of the story – there's basically no way to keep reading these essays without getting major spoilers, so please read MAW before you scroll down.

In many ways, Wendy Weber is the slasher-movie teenager of Maw. She does everything that decades of Scream movies have taught us to avoid: She insists on a vacation in a secluded area with a history of occultism. She slips away from the group to smoke pot. She tries to have sex outside of marriage.

Our Wendy is a middle-aged mother of two, though, and not a high school student. Her offense isn’t letting her boyfriend over to neck while she’s supposed to be babysitting, it’s getting bored with her marriage and trying to have an affair with a younger man. She is the most overtly “normal” woman in the story — blonde, white, suburban, wealthy, with politics that don’t really extend beyond a vague appreciation for female “empowerment” — and the least angry. She’s disconnected and full of bourgeois anomie, clinging to GOOP-style “wellness” to conceal her lack of direction.

This makes her a slightly better surrogate for the reader than Marion, who is overtly weird and damaged from the get-go, but it will also make certain readers dislike her. It’s supposed to. Horror, as many people envision it, exists to punish women that the audience doesn’t like. The blonde who takes her top off gets it in the neck. The mean girls get mean deaths. Even being too successfully girly can do it: Women who get “hysterical,” who cry or run away from danger, never survive. Only a woman who conforms to every rule of virtuous femininity — virgin or married, stainless and sinless, feminine but not girly, strong but not aggressive, willing to exhibit selfless devotion to a child or at least a cat — can get through intact.

Wendy is not perfect. She’s too much of a good girl to be interesting, but not good enough to be good; not young or hip enough to appeal to most male gazes, yet not content to be asexual and invisible, either; a wife who neglects her husband, a mother who hasn’t been fulfilled by kids. Worse than that, she’s basic. She’s pumpkin spice. She’s “Live Laugh Love.” She’s a #NastyWoman. If you saw Wendy’s Instagram feed, with its perfectly manicured grid of apple-picking and birthday cakes and yoga poses, you’d most likely roll your eyes and assume this woman had no real problems and nothing worthwhile to say. This would be true even — especially? — if you’re a feminist yourself.

Wendy fits squarely into the box of women that we’re allowed to dislike, but disliking her is, as always, a way to avoid reckoning with her humanity. Maw has to make you care about Wendy. It has to ask you if you’re really ready to write off this entire human being just because she’s not as edgy as you’d like to think you are. I love Wendy, and have loved a lot of women who remind me a little bit of Wendy, and I do think she has real problems. At least, I gave her the realest problems I had.

I didn’t exactly know I would transition, when I started Maw, but I knew something huge was coming, and that it would change, or ruin, my life. I stashed those fears and vulnerabilities where I thought they would be safe, in the character furthest away from my persona. Wendy, the apolitical suburban housewife, is also a fairly direct reflection of what it feels like to be closeted and on the verge of coming out.

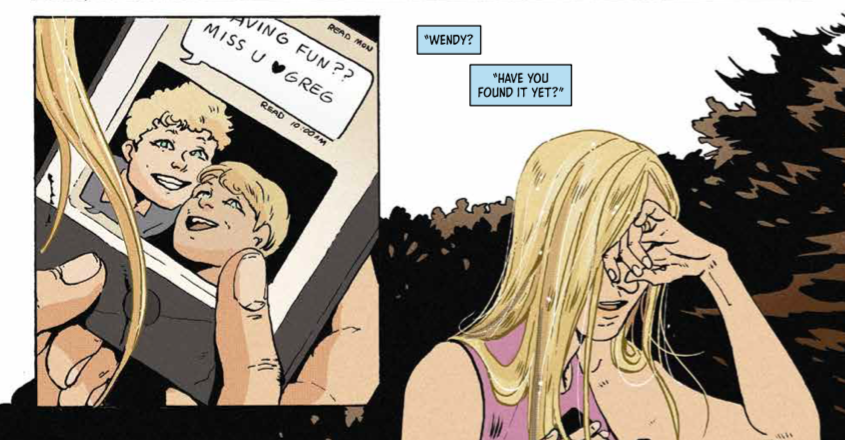

There are a lot of jokes about Wendy potentially being gay. I thought I was being subtle, but they just keep happening. Wendy isn’t happy in her marriage, but it’s also not clear what the issue with her marriage is — her husband is a perfectly nice man, but they just don’t talk to each other or spend time together. Her kids are lovely, but the mind-blowing, all-encompassing joy she’s supposed to have gotten from motherhood just never happened. It’s as if she’s subletting someone else’s family. They’re great, but they’re also not hers.

Wendy’s problem isn’t caused by some singular, horrible event. It can’t be resolved with a vacation or a bender or a quick fix like hooking up with Howie. He’s right that she’s not interested in him so much as the aftermath of him; she wants to create some disaster that she can point to as “the reason” her marriage failed. There’s no name she can give her discontent. (Historically, housewives do have a tendency to run into problems without a name.) There’s only the sense that what she is doing now is overwhelmingly, painfully inauthentic.

“All I have to do is be who they expect me to be,” Wendy says, but that person is not her. She’s on the island, not to fix anything, but to “find out what else I am.” Whatever is under her surface, it’s not the person she’s expected to be, and it may not be someone who can win the world’s approval. She’s frozen, terrified, in the waiting room that leads to her new life, waiting to see what will blow up and who will disappear.

I don’t think Wendy is trans, and I don’t know if Wendy is queer. I have no idea who the real Wendy is, and neither does she, because at the moment we meet her, she is only just beginning to ask that question. Wendy is reaching out for life — flailing around in the dark, trying to grab hold of some authentic way of being that may or may not exist for her. It’s awkward, and messy, and selfish, and until she finds it, her whole life will be one long act of desperation.

My means of dealing with those questions were different than Wendy’s. She kissed a weed dealer, I wrote a comic book. Like Wendy, though, I find that spiritual bypassing — like sex, like drugs — is a powerful vice. If you can just transcend, learn to meditate, read your Tarot, do yoga, figure out herbal medicine, if you can just pray long enough and hard enough, maybe you won’t need to face your problems, let alone fix them. Maybe you’ll just become serene and enlightened enough that your problems won’t matter. I always wanted to be Gwyneth Paltrow, I used to say, and I meant it. Gwyneth Paltrow seems really happy about being Gwyneth Paltrow. I wasn’t at all happy about being me.

All this woo that Wendy’s into, the shimmery holographic-foil Tarot cards and rose quartz and $40 jars of mushroom dust — stuff that I am, to be fair, very often into — well, it’s soothing. It’s pretty. It’s gentle. It’s meant to make her feel better. Wendy spends her whole life making other people feel better, whether it’s her kids or her husband or her slow-motion car crash of a sister; how often does anyone bother to soothe her? How often do other people actively go out of their way to make sure Wendy Weber is okay?

They don’t. The world looks at Wendy and sees someone who provides care, not someone who needs it. She has to care for herself, and “self-care,” in a capitalist world, comes with a price tag. She’s numbing out with consumerist “spirituality,” no different than Marion with her alcohol and Howie with his weed — grabbing at the first thing that makes her feel better, even if it’s bullshit. Maybe a more radical person than I would look down on Wendy; then again, most radicals are familiar with the saying about religion and opiates. People start taking opiates because they’re in pain.

This is not to say Wendy is dealing with her pain appropriately. Snake-oil salesmen and cult leaders are successful for the same reason: They care when no-one else does. Or, at least, they seem to care, long enough to sell you something. When you’re lonely enough, friendship and salesmanship start to feel like the same thing. Yet, once you’ve started to delude yourself, other people are typically more than happy to keep deluding you. There is tremendous harm in what we call “wellness.” People start with believing in crystals and deep breathing and adaptogens, and they end up believing in cannibal cults and storming the Capitol. Wendy is not the first suburban mom whose wellness journey ends in a much darker place than she’d planned.

If Wendy could truly grapple with that pain and the forces causing it — compulsory heterosexuality, patriarchy, whiteness and capitalism and the ideals of white feminine “success” she’s learned to embody — she might end up somewhere different. She might realize that her pain is not wrong or crazy, and that she doesn’t need fixing; unhappiness is a rational reaction to an unfair world. I believe Wendy has that in her. Everyone else on that commune is there to heal from some wrong done to them. Wendy is the only person who’s there to help someone else — Marion, her sister. Wendy understands that injustice matters even when it doesn’t affect her personally. If she could just follow that understanding, she’d be fine.

First, though, Wendy has to stop being Wendy. Whatever life she’s built, whatever accomplishments she’s racked up, whatever loves she’s secured, whatever performance she’s mastered, none of it can stay, because none of it is working. Wendy has to let that version of herself fall away so that some new person can emerge. There’s no guarantee of who that person will be, or whether her life will be happy, but every birth is like that. The alternative to birth is a life that doesn't feel like living; to walk through the world with no-one, not even you, knowing who you are.

Other inspirations for Wendy:

- Various musical expressions of high-femme despair, particularly this one.

- The unhappy wives of horror: Rosemary in Rosemary's Baby, Wendy Torrance in The Shining.

- Gwyneth Paltrow if she were a Gwyneth Paltrow fan.

- The "nice" sister in every horror story about two sisters: Brigitte in Ginger Snaps, Needy in Jennifer's Body, Justine in Raw.

- The frighteningly accurate maternal depression in The Babadook: "Come see, come see what's underneath."

- The radiant despair I experience after 20 - 30 minutes on Pinterest.

- Every fucking Tarot deck I own.