Little Terrors: The Neighbors #2

Here we are again! Issue #2 of The Neighbors, my comic with the astonishing Letizia Cadonici, is on sale today. You can pick it up at your local comic shop, or get an e-reader version on Comixology and Google Play. If you like it, tell a friend. If you don't like it, tell an enemy to read it instead. Really, any sale helps.

“Mary Katherine must never be punished. Must never be sent to bed without her dinner. Mary Katherine will never allow herself to do anything inviting punishment.”

“Our beloved, our dearest Mary Katherine must be guarded and cherished. Thomas, give your sister your dinner; she would like more to eat.”

“Dorothy — Julien. Rise when our beloved daughter rises.”

“Bow all your heads to our adored Mary Katherine.”

— Shirley Jackson, We Have Always Lived In The Castle

My mother used to read me Shirley Jackson stories at bedtime. Jackson famously had two careers — as a horror writer, which is how we all know her, and as a writer of light, funny housewife essays, which, last I checked, were all out of print. Jackson was my mother’s favorite author, so she tracked down the essays, and when I was going to bed, she’d come in and read a few before saying goodnight.

Even among those stories, I liked the spooky ones best. I could swear to you that “Charles” — which is about a little boy who comes home with more and more appalling stories about a seemingly sociopathic classmate named “Charles,” only for his parents to be told, by a teacher, that there are serious problems with their son’s behavior, and that there is no “Charles” in his class — appeared as an essay in the parenting books before it was collected as a short story.

There’s another story, one I can’t place — I could almost be imagining it, but I swear it’s real — about one of Jackson’s little girls, who makes contact with some other world out in the woods. It seems like a cute little story about a kid with imaginary friends, until a series of coincidences starts to indicate there is, in fact, something out there, and that her kid has been talking to it. Jackson leaves the door open on that one, refusing to say whether the beings in the woods were real or not; the effect is probably intended to be whimsical. I found it horrifying.

“Charles” and the long-lost, possibly-apocryphal story about the girl in the woods are both woven into the fabric of “The Neighbors.” They are both great stories about how children — with their wide-open imaginations, and their loose grasp on consequences or conventional morality — can be terrifying.

Jackson’s best story along these lines is a book I read by accident. One day, when I was seven or eight years old, I got bored and found a name I recognized on my mother’s bookshelf. I chose the thinnest book, the one with the young girl and the cat on the cover — it didn’t look much different than The Girl With the Silver Eyes, or any of the age-appropriate “chapter books” I was supposed to be reading — and opened it.

“My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance,” the book began, sounding exactly like one of those chapter books. “I have often thought that with any luck at all, I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both of my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had.” Merricat goes on to tell us that when she walks through town, she pretends she’s playing a board game, and that no-one in town likes her, and that she likes to imagine living in a little house all by herself on the moon.

See what I mean? Whimsy! So I read on, prepared for yet another story about a somewhat-magical, quirky teen girl whose boring normie peers didn’t get her, and by the time I figured out why no-one in town liked Merricat — it is very, very deserved — I was halfway through my first horror novel.

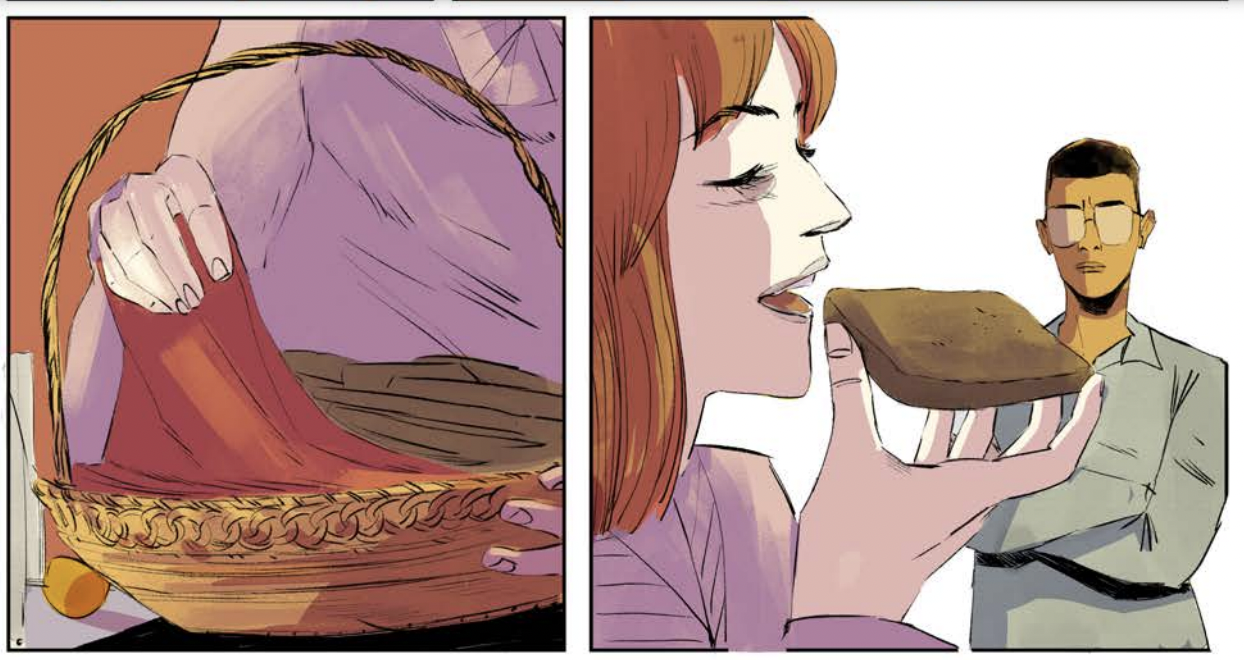

The Neighbors is a story about family, and as such, it felt right to revisit my mother’s favorite novelist for inspiration. It is also — as you know by now — a story about a feral teenage girl, and as such, We Have Always Lived In The Castle is all over it. Even the look of the character (white hair, dark rings around her eyes) is probably an unconscious homage to the Merricat on my edition’s cover.

Casey has a childish, Charles-ish tendency to be intensely destructive while denying her own role in it. She has a Merricat-like opacity; she’s always thinking, always deep in her own mental universe, but you and I can’t get in there. Whatever goes on in Casey’s mind, it does not entail a conventional sense of right and wrong. She’s cruel just to see how people react to her. She breaks things just to see how they fall. She’s playing a game that only she knows, making her own fun, and Casey’s fun is awful.

I mean, this is also just how kids are sometimes. It’s how I recall being at my worst. Making Casey the monster doesn’t mean I dislike her. (In several early drafts, she was the protagonist.) The monster is just the best character to be. They get the best lines, the best moments; they usually make the best points, because they don’t have to be nice or relatable, and they can just tell the truth.

This, of course, begs the question of what point Casey is making. In her book Abolish the Family, the feminist critic Sophie Lewis cites Tony Williams to argue that horror is “a popular vehicle for mass anti-family desire.”

“In slasher, home-invasion and feminist horror canons, the narrative pretends to worry nationalistically about external threats to the family while, in fact, indulging every conceivable fantasy of dismembering and setting fire to it from within,” Lewis writes. “In these [stories], the suppressed, disavowed violence of the home is returning home. The monster is coming from inside the house.”

I read Abolish the Family after turning in scripts for The Neighbors, but this is nonetheless a pretty concise summary of Casey’s function. She is the only character who seems to feel that Janet has abandoned queerness by marrying a man or by moving away from the city to a small town where she'll be presumed straight; she's the one who won't stop bringing up the divorce; she has an older sibling's fear of being replaced by a newer, cuter baby, and a teenager's disillusionment as she realizes that her parents are not necessarily any smarter than she is. Casey is not so much destroying her family as she is revealing all the fractures and fault lines that already exist within it. She refuses to pretend that (a) the Shipton-Gowdies are a "normal," functioning nuclear family or that (b) being part of such a family is a desirable thing.

Lewis’s list of genres, though, is missing the most common form of anti-family horror: The haunted house story. A ghost is a chunk of the past that has broken off and started rattling around inside the present. It’s a secret, or a trauma, that can’t be released until it is faced. Like any trauma, the ghost will manifest destructively and even violently until it’s acknowledged. Stories about haunted houses are stories about the families who live in those houses, and the truths those families refuse to deal with; they’re about the hold our history has on us, whether we face it or not.

Ghosts are the most relatable monsters, because they just want us to know what happened to them. They want us to integrate their suffering into our acknowledged history. Monsters are agents of clarity. They cut through whatever it is you’re hiding. Ghosts force us to see the world as it is, and all the darkness in it, and that is what Casey — the ghost haunting her own house — is set to do.

Inspiration

As promised, a quick list of works that inspired the Gothic elements and haunted-house styling of The Neighbors.

The Haunting. (Robert Wise, 1963.) This is the definitive screen adaptation of Jackson (though the book is still scarier) and it has what every haunted house story needs: A fucking great house. Hill House has to be “not sane,” possessed of its own overwhelming energy; the movie accomplishes this through insistently unpleasant set design. Every frame is cluttered and oddly angled and subtly or not-so-subtly disorienting, filling our eye with the house’s unwelcome presence, and refusing to let us focus on the human characters. Hill House doesn’t like people, but more importantly, she will not be upstaged by them, and that’s what makes her feel so angrily alive.

Crimson Peak. (Guillermo Del Toro, 2015.) This was the second major visual reference for The Neighbors, and again, it’s about the house: The titular English manor, which Del Toro built specifically for the movie, is hyper-real, part fairy tale and part memory, an R-rated version of Disney’s Haunted Mansion. The whole movie is so saturated with color and texture you can hardly avoid the word “sumptuous;” once they get to that mansion, you could take a still shot of almost any frame and hang it in a museum. The beauty simultaneously draws us in and repulses us, capturing the whole mood of Gothic horror in one set.

The Others. (Alejandro Amenábar, 2001). Haunted-house stories are about the family history nobody wants to acknowledge. The Haunting makes more sense if Nell killed her mother. The siblings in Crimson Peak are not what they seem. The Others is a perfect haunted-house movie because it is willing to go to such bad places with its family, and because it trusts that the culture’s knee-jerk sympathy for a willowy white lady in danger (Nicole Kidman, doing some of her willowiest work here) will keep us from seeing what’s going on.

The Shining. (Stanley Kubrick, 1980.) Obviously. This is the Rolls Royce of haunted house movies, and there’s almost no point in saying anything more about it, but I appreciate it for proving that everything is more horrible when done to a child (poor Danny!!) or done by a child (not the twins!!!!).

We Have Always Lived in the Castle. (Shirley Jackson, 1962.) I honestly can’t say enough about it. Skip the movie.

GROSS FOLKLORE CORNER

“Sibley determined to catch a witch. At her instruction, John, the Parrises’ Indian slave, mixed the girls’ urine into a rye-flour cake, baked amid the embers on the hearth. Sibley then fed the concoction to the family dog. There was some fogginess about how the countermagic worked — by drawing the witch to the animal, by transferring the spell to it, or by scalding the witch — but the old English recipe could be trusted to reveal the guilty party.” — The Witches: Suspicion, Betrayal and Hysteria in 1692 Salem, by Stacy Schiff.

“So, how exactly did witch bottles work? Per JSTOR Daily's Allison C. Meier, practitioners filled the vessels with an assortment of items, but most commonly urine and bent pins. The urine was believed to lure witches traveling through a supernatural ‘otherworld’ into the bottle, where they would then be trapped on the pins’ sharp points.” — “‘Witch Bottle’ Filled With Teeth, Pins and Mysterious Liquid Discovered in English Chimney,” Smithsonian Magazine.