It's Underneath Us: The Neighbors #4

The day I've been waiting for is finally here! The next-to-last issue of The Neighbors, AKA my favorite issue, AKA the special-interest-indulging Goth fantasia of my dreams, goes on sale today. Go grab an issue at your local comic shop, or buy an e-reader version on Comixology and Google Play.

This is the penultimate issue; we're deep in the story now, and there's absolutely no way to read the essay below without getting spoiled. So don't read it before you've gotten through the issue. If you do, and you like it: Please tell a friend. It helps a lot more than you'd think.

"They needn't be afraid," he said, "we're good neighbors, but let them not say too much if the milk might go from the cows now and again." — Lady Gregory, Visions and Beliefs in the West of Ireland

There is a monster that will not let you speak its name. There is a monster who will only spare those who flatter it. There is a monster under the earth, and it takes things, and when you speak of this monster, you must only use kind words, admiring words, words that make the monster think you respect it and envy it and love it. If you insult the monster, if you speak ill of the monster, the next thing it will take is you.

So call it by a name that it likes, a name it’s chosen. Call them something that makes them sound friendly: The good people. The gentlefolk. The fair folk. Our good neighbors.

“They never gave me anything did me good, but a good deal of torment I had from them. And they're often walking the road, and if you met them you wouldn't know them from any other person,” says Mrs. Sheridan, the Irish peasant who was told to stay quiet about her stolen food.

Sheridan lived in a time and place where food mattered. There wasn’t much of it. To know that it could go missing, and that there was nothing she could do but smile and play along, would have been hard. Still, it was far from the worst thing her neighbors did.

Mrs. Sheridan says that her baby died, when he was a year and a half old, and she heard him later crying from far away, so she knew they had taken him. She says that they took away her ability to walk, and that when her father managed to cure her, they killed him. (“But there's no harm at all in them, not much harm,” Mrs. Sheridan adds here. She always adds something like this, when she’s said too much.) She says that her husband died in bed next to her, and she could hear — but not see — someone else in the room: “I heard the bones of his neck crack, and he gave a sort of a choked laugh, and I got out of the bed and struck a light and I saw nothing, but I thought I saw some one go through the door.”

Most of the time, they look human, or they look like nothing. You can detect them only when something starts to go wrong. Once, Mrs. Sheridan says, something that looked like a man walked with her one night, getting taller and taller as it walked, “and when he came to where the caves go underground he stopped, and I asked him his name, and he said, ‘You should know me, for you've seen me often enough.’ And then he was gone, and I know that he was no living thing.” Later, two little boys in her village supposedly drowned, but they didn’t drown; she saw a tall woman leading them away toward the caves. Small corpses were later recovered, but whatever they might have been, they were not the boys.

They can come at any time. They can come for anyone. They can be anywhere, or look like anybody. Mrs. Sheridan knows only one protection: “When you speak of them you should always say the day of the week,” she tells Lady Gregory. “Maybe you didn't notice that I said, ‘This is Friday’ just when we were hardly in at the gate.” Saying the day of the week keeps them from listening.

So that’s what Mrs. Sheridan has lived with, every day of her life, and she’s a very old woman, so maybe she’s senile, or superstitious, or crazy. But you also have to consider the possibility that she believes everything she’s saying.

I have loved these stories since childhood, but I have very rarely seen them adapted or retold in a way that captures how the actual folklore feels. A lot of scholars have floated theories about what the neighbors might be — gods, or ghosts, or remnants from some forgotten tradition of ancestor worship — but the most important thing to know is that they are power. They are The Rules. They are the social order that cannot be broken, or changed, and that will always punish deviants. (The neighbors stole or killed humans for disobedience, but also for being exceptional: Pretty people, promising artists, people who were talented or who stood out, were often the first taken.) They are a reminder that the human world has limits, and that we are surrounded by things we neither understand nor control, and that when you transgress the limits of the known world, bad shit happens.

Call something like that a “fairy,” and people do worse than punish you. They laugh. They stop understanding why it’s scary. A name puts a handle on a thing and makes it knowable, and people think they know what “fairies” are. Their definition does not include Mrs. Sheridan. It doesn’t include the thing that gets into your room, in the night, through the door, and leaves you lying next to the corpse of someone you love.

So I haven’t used the other name until now, and I won’t use it again. You will never find that word in The Neighbors, because I want to give you, not the name for the thing, but the thing itself. Normally, for these newsletters, I present a list of inspirations and some folklore, but in this case, the inspiration is the folklore, so I’ll just point out some rules that you should know.

The Neighbors always live underground. There are many descriptions of their world: We know that time doesn’t work down there. We know that you cannot eat the food, or something terrible will happen. In many stories, it looks like a lush green field, or the inside of a castle, but when the magic wears off, the captured human will perceive it as a field of bones.

My favorite description comes from Sir Orfeo, an old Breton lay recommended to me by my friend Inigo Purcell; it looks like the world you left, but it’s dead quiet, and everyone who was ever taken is lying down, perfectly still, frozen in the exact moment of their capture.

“My father never told me a word o’ them things. No. But when we were young, he did something that gave me a suspicion of it. He got a piece o’ that strong cord and he got a lot of old rusty horseshoe nails… he bended them in and made a ring of ‘em and put the cord through ‘em, and hung ‘em around our necks. Don’t you know why he done it? The fairies couldn’t touch you then, you see!” — Meeting the Other Crowd, Eddie Lenihan

Every gift Agnes gives to Isobel is some kind of protection. The Brigid’s cross protects from fire and evil spirits. Salted fish (from Issue Two) is, I believe, Scandinavian (Agnes uses a tin of anchovies). The witch bottle traps unwelcome spirits. The Neighbors can’t touch iron, and they can’t eat bread (the diner in town doesn’t serve anything with bread in it, or anything except for meat, potatoes and dairy, because that’s all they’re known to eat). The problem is that all of it looks spooky as shit, and Agnes can’t tell anyone what it’s for, because Casey is listening. The necklace of nails, in particular, seemed like a risk.

Janet comes to Carter Hall in Issue Three, and again in this issue. (There is not much difference between a banquet hall and a good bar.) Tam Lin is one of the most popular Child ballads in part because Janet is such a great character: The ballad opens with the women of the town being warned never to go to Carter Hall, because some kind of terrible sex ghost is known to fuck anyone who enters. In the very next line, Janet is introduced, hiking her skirt up and heading “off to Carter Hall, as fast as go can she.”

So Janet is somebody who knows what she wants, and she remains similarly fearless and self-possessed for the rest of the story, in which she learns that her new boyfriend, Sir Sex Ghost, is actually a human being held captive by fairies, and that she can free him if she keeps holding him and recognizing him through a series of frightening transformations. The challenge of loving someone, even when they are held captive by their past, even when they change or look different, seemed like a good fit for Janet and Oliver’s particular story.

The concept of transferring your own death to an animal comes from several different spells, all of which I found in The Devil’s Plantation: East Anglian Lore, Witchcraft and Folk Magic by Nigel G. Pearson. First, it could be done by rubbing a toad against the sick person’s chest and burying it alive; curing warts was also done by rubbing one live snail on each wart and impaling each snail on “a blackthorn spike.” Bigger curses need bigger cures, though, and neither a snail nor a frog seemed cute enough to elicit sympathy. The idea of using a bird comes from an anti-witchcraft charm, also detailed by Pearson, in which a woman whose geese were bewitched (it happens to the best of us) stuck nine metal pins in the chest of her most disobedient goose and roasted it alive.

The Tom Shucks are the Fear Dorcha, or Dark Man, a tall man all in black who “serves as the fairy Queen's Taker, as it was known, when she needed a mortal he'd be the one sent to gather them.” The Dark Man is known to “carry out her commands without emotion or waste of energy.” Again, this all sounds cute and fey and Celtic until you translate it into a visual idiom, and then it's just Hellraiser with an Irish accent.

Cunnanock has more than one Dark Man, and he has more than one origin: Tom’s name comes from the English Black Shuck, a huge black dog the size of a pony that could only be seen at night, and whose appearance portended death. Tom’s dog, however, is a white hound. In the Welsh Mabinogion, the Cwn Annwn — fairy dogs — are white hunting hounds with red ears, and when the prince Pwyll interferes with their hunt, he’s taken down to the Underworld.

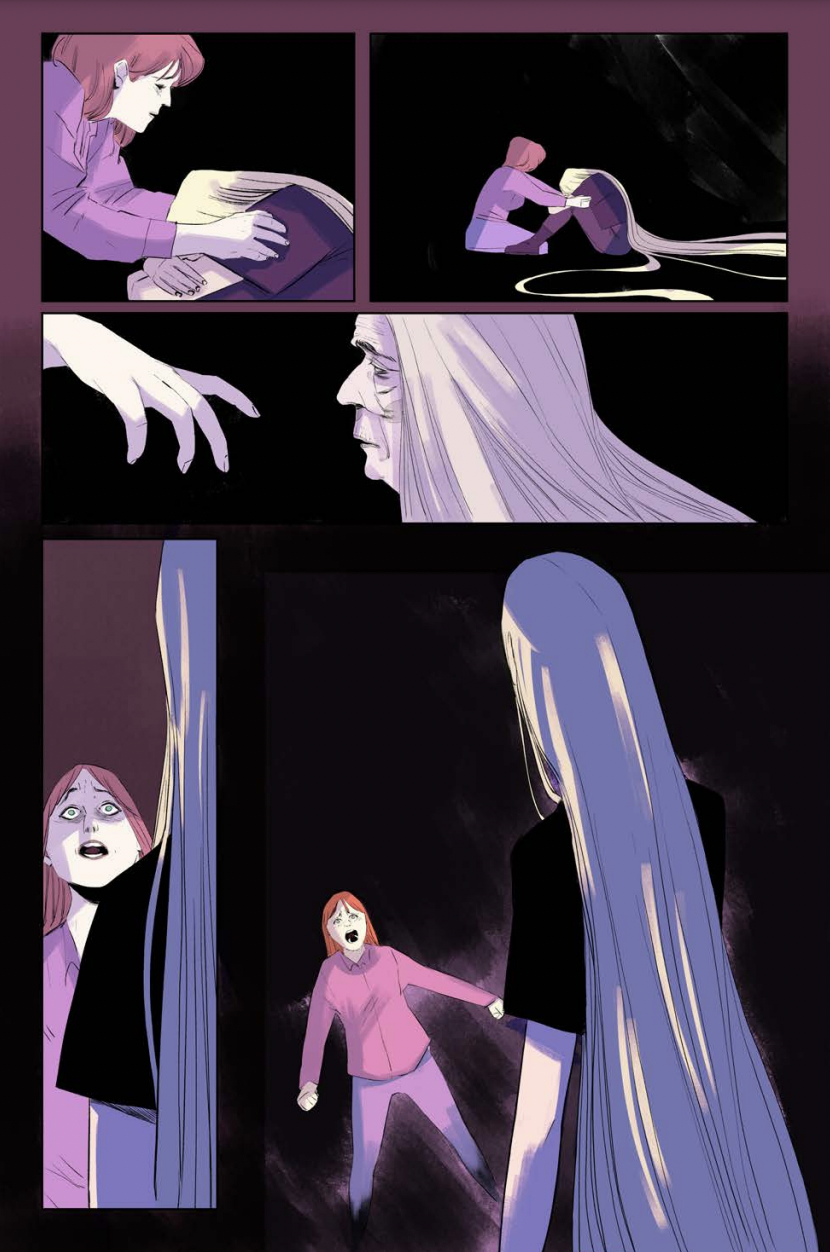

“And there, God be good to us! in a cantle o' the wall I seen an ould woman, as I thought, sittin' on her hunkers, all crouched together, an' her head bowed down, seemin'ly in the greatest affliction. I made for to touch her on the shouldher, on'y somethin' stopt me, for as I looked closer at her I saw she was no more an ould woman nor she was an ould cat. The first thing I tuk notice to, Misther Harry, was her hair, that was sthreelin' down over his showldhers, an' a good yard on the ground on aich side of her… she turned her face on me. Aw, Misther Harry, but 'twas that was the awfullest apparation ever I seen, the face of her as she looked up at me… as pale as a corpse, an' a most o' freckles on it, like the freckles on a turkey's egg; an' the two eyes sewn in wid red thread, from the terrible power o' crying the' had to do; an' such a pair iv eyes as the' wor, Misther Harry, as blue as two forget-me-nots, an' as cowld as the moon in a bog-hole of a frosty night, an' a dead-an'-live look in them that sent a cowld shiver through the marra o' me bones… she riz up from her hunkers, till, bedad! she looked mostly as tall as Nelson's Pillar.” — W.B. Yeats, Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry

Her name is the Banshee. She means that someone is going to die.