Gender Performance: Audition (Takashi Miike, 1999)

He ran into my acupuncture needle. He ran into my acupuncture needle SIXTEEN ENTIRELY PAINLESS TIMES.

Welcome to the Halloween Special! It's a month-long run of free content, because I love Halloween more than life, and I cannot bear to love it alone.

To celebrate the release of MAW, this year's theme is THEY WANT REVENGE. I'm writing up some of the best and most powerful horror movies about sexual assault and the rage that follows in its wake. My goal is to be survivor-focused, but some of these movies are heavy; judge your own limits.

The Halloween Special is also my chance to raise funds for causes I care about. This year, subscriptions to the paid newsletter will be 30% off with the code HALLOWEEN21. 100% of the subscription money I generate in October will be sent to the National Network of Abortion Funds.

If you want to support me directly, MAW is available in comic shops, and I'd love you to buy a copy. Either way, everyone deserves to control their own body.

There’s a point in Audition — about 43 minutes in, if you’re waiting for it — where you realize you’ve been watching the wrong movie. For nearly an hour, Audition has seemed like a sappy, not-that-great romantic comedy about a well-meaning widower who’s learning to love again. There’s yearning piano on the soundtrack; there are wacky montages; there’s a dusting of casual misogyny, and some objectification, and a “romance” between a dude in his 50s and the 24-year-old girl he’s lured with false promises of professional advancement.

Then you hit the 43-minute mark, and we see the inside of the girl’s apartment. The viewer’s stomach drops; their heart rate rises; the greatest rape-revenge movie in the canon is well underway. I’m going to try to be measured, in my Audition review, but that’s going to be difficult, because dear sweet merciful Hoobastank, I fucking love this movie. Specifically, I love what it does to men.

Long before I watched Audition, I was familiar with it as one of the most disturbing movies ever made. I saw dozens of reviews and best-of lists and comment-section rants about how horrific it was, what an endurance test it was to watch, how it made grown men vomit or gave them nightmares. One AV Club comment section alone uncovers dudes complaining that "[watching] it pollutes your soul," that "there is no good argument for making or liking these kinds of movies," that viewers were unable to anticipate "just how depraved and gruesome it eventually becomes" because "the director has chosen to behave like a conniving, scheming, opportunistic predator. I don't mean that in a good way." (No shit.) No less a critic than Robin Wood wrote that Audition was "almost as unwatchable as the newsreels – of Auschwitz, of the innocent victims of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and Vietnam, victims of Nazi or American dehumanization."

Tone it down there, Rob. There is, in fact, very little violence in Audition, and what violence we do see is understated — the darkest acts are implied, rather than shown. The torture sequence, often cited as an inspiration for the torture porn wave of the 2000s, is an acupuncture session. The “torturer” gives us some exposition about how her “victim” has been drugged so that he’s sensitive to needles, and how whatever she’s doing will be super-duper painful, but even so, I used to pay $50 to have this stuff done to my bad knee. It’s immensely silly, and it takes a committed performance from both actors to convince us that anyone is being hurt.

The utter, pants-shitting terror evinced by all those male viewers doesn’t stem from what’s being done, but from who’s doing it, and why. Audition does a tremendously good job of appealing to shitty straight men — their entitlements, their ambitions, their resentments and longings, the way they see the world — and then, once it’s won them over and convinced them to feel safe and supported, it turns the tables and subjects their narrative surrogate to horrendous violence.

Which is to say, Audition does to shitty men what shitty men do to women every single day. It’s not a fun feeling. It’s fun for me to observe, though, because I know those men are probably having it for the first time.

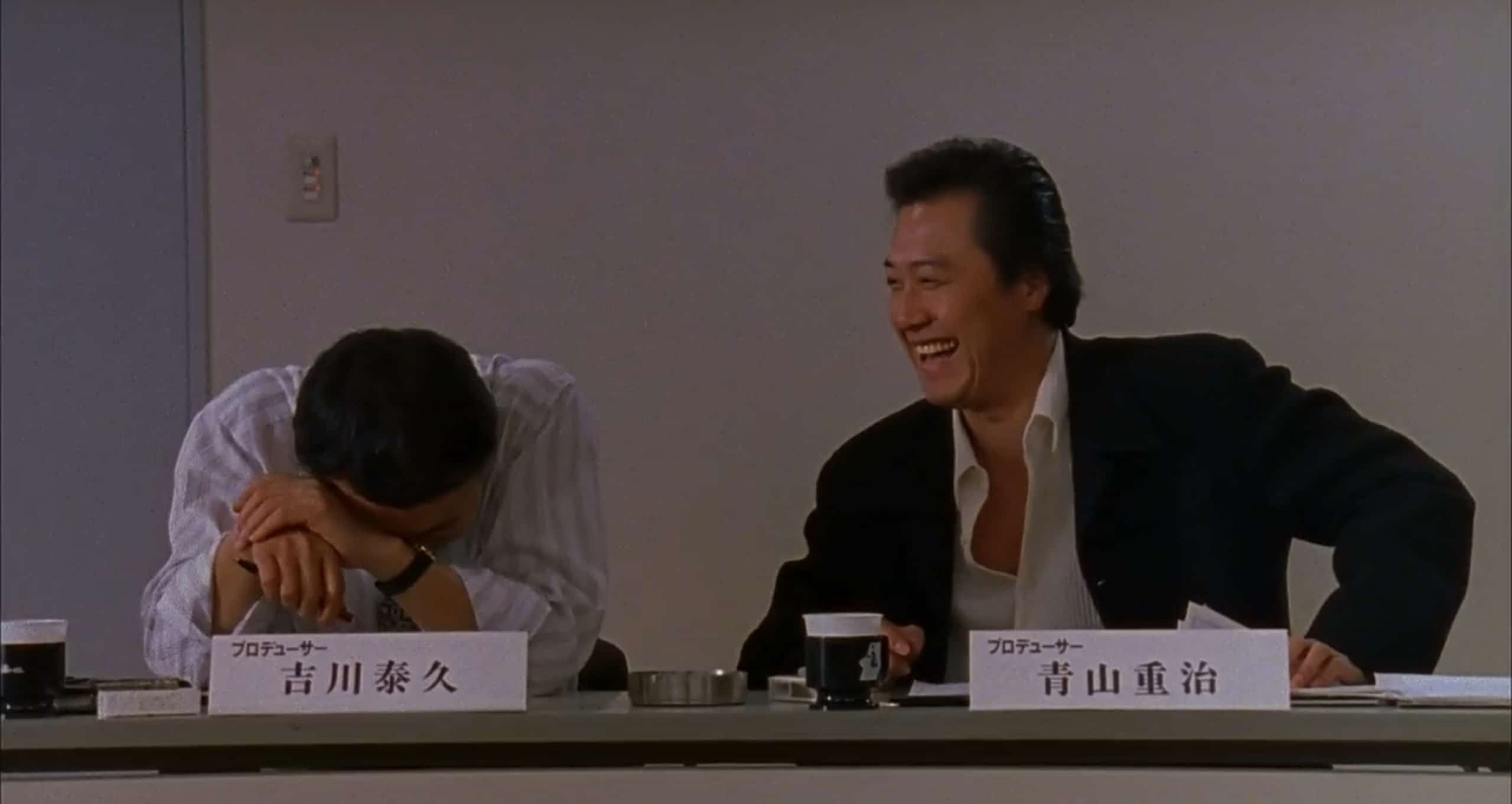

The titular audition is run by Aoyama, the sort of rumpled, kind-of-cute, “relatable” nice-guy protagonist you’ve seen in a zillion romantic comedies. Aoyama’s teenage son thinks he ought to get remarried, because he seems lonely. (Aoyama’s “loneliness” is sometimes evinced by checking out the son’s underage girlfriend, but Junior doesn’t mention it.) When Aoyama goes out for drinks with his buddy, they bond over the knowledge that all the women Aoyama might date are terrible: “Awful girls, common, full of themselves. Stupid, all of them. Where are the nice ones?”

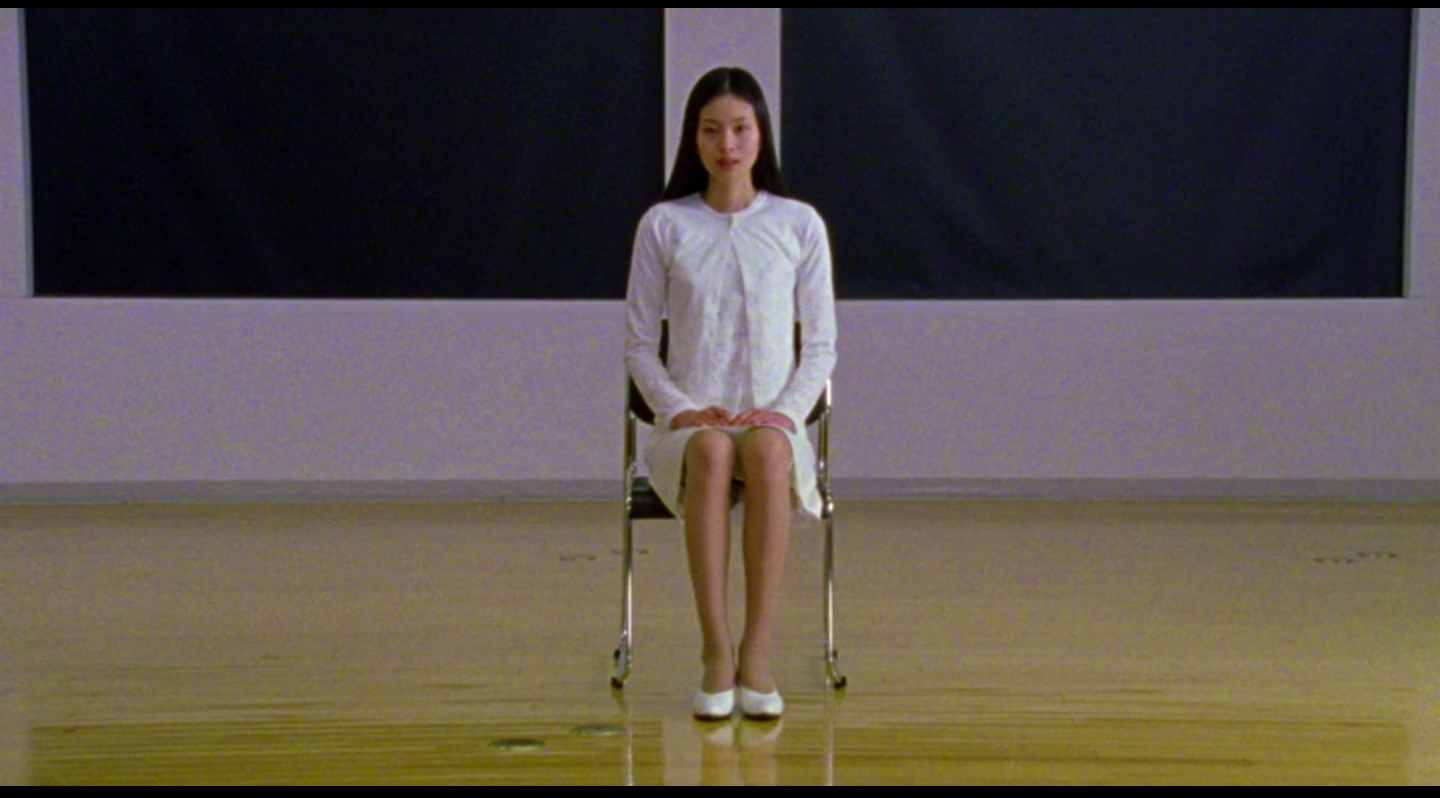

Not in this movie, you wretched fuck! But Aoyama works in the movie business, and as such, he can stage an event where women twenty years younger and ten times hotter than he is will have to impress him. He creates an “audition” for a fake romantic comedy, fully intending to make his favorite actress date him. By the time the audition starts, though, he’s already chosen the woman he wants to take home — the smallest, meekest, most submissive, most childlike, least threatening 24-year-old girl in the entire universe.

Her name is Asami. She seems nice.

How you read Audition boils down to whether you think Aoyama has it coming. It is possible to read him as an innocent victim, and Asami as a scheming, irrational, vindictive monster — a clingy Psycho Bitch(TM) who gets mad at her perfectly nice boyfriend for no good reason and decides to torture him, because that’s what women do.

It is possible to read Aoyama that way, but not if you’ve seen the “audition” he puts those women through, which clearly crosses the border into sexual harassment, if not sexual assault. Aoyama makes the women cry. He makes them strip. Others are pressured to disclose their most personal traumas — we see women talking about professional failures, bad parents, difficult childhoods. The second instance of stripping smash-cuts right to a different woman talking about her suicide attempts. No-one at the audition is ever invited to act, and the questions they're asked have nothing to do with work. Here are a few:

Have you had loveless sex?

Are you into drugs?

Would you work in the sex industry?

What are men to you?

What kind of men do you hate?

You can’t say it’s about intimacy. The women are trying to get hired; they have to come up with “likable,” impressive answers to questions no-one should ever be asked at work. The men on the other side of the table have all the power, and can cast those women aside if they fail to measure up.

This is done in a wacky montage, with lite jazz playing underneath it, so it's not overtly flagged as disturbing material. The scene is a test — the movie is feeling out your limits, seeing how willing you are to cosign Aoyama’s misogyny, playing into your conviction (if you have one) that sexual harassment is normal and cool and fun. The extent to which you accept Aoyama’s violence is the extent to which Asami’s violence will seem scary and crazy to you later. The movie will upset you more if you deserve to be upset, which is only fair.

It’s also clear that Aoyama is led to his sad, needle-ful end because he’s a dummy. Asami’s cover story barely deserves the name: She name-checks a producer, then admits she doesn’t know him. She “works” at a “bar” which Aoyama is forbidden to visit. Even Aoyama’s equally gross guy friend begs him to choose some other girl — there’s something weird about this one, something artificial in the baby voice and timid posture and utterly empty eyes.

Aoyama doesn’t notice. He’s not “in love” with Asami, but with his vision of who Asami ought to be. He’s got an idea of a perfectly submissive, innocent, old-fashioned girl who is also hot and young and sexually receptive, and he is determined to project that perfect woman onto some warm body, whether the woman in the body likes it or not. His fantasy takes precedence over the humanity of the person he’s dating. Granted, he didn’t expect to get it quite this wrong, but he didn’t care enough to get it right.

One of the movie’s most important scenes, the first date between Aoyama and Asami, plays out twice. In the first iteration, Aoyama asks about Asami’s family, and she gives him a boring answer — they’re fine, they don’t talk much, whatever. It’s a banal interaction that is only notable because of several odd little skips in the film. In the second take, which is part of a dream sequence, Asami narrates a childhood of immense suffering — traded from adult to adult, constant abuse, violence and loneliness and longing to die. Aoyama is dreaming, so we can’t know how true it is, but the film is not skipping any more.

Did Asami lie about her family on that first date? Or was Aoyama just not listening when she told him about her abuse? There’s a huge amount of buried trauma inside Asami, waiting to erupt, but what this scene seems to suggest is that her damage was not hidden so much as it was intentionally overlooked for the sake of other people's convenience. The second date ends the same way as the first one. No matter what story Asami tells him, Aoyama doesn’t care.

He will care. Eventually, when he has to, Aoyama will care very much. That’s where the needles and piano wire come in.

Asami is the cinematic monster I most connect with. Of all the villains in horror movies, her dark side bears the closest resemblance to my own. I remember saying this often, when doing press for Dead Blondes, my book on “female monsters,” and it caused me to approach the movie with a lot of trepidation, when it came time to rewatch it. Asami is hyperfeminine, defined by hyperfemininity in fact, and I’m hopefully not. I thought the comparison was probably shameful, one more instance of overcompensation from the years when I was trying to be a girl.

Yet Asami is not remotely feminine. Not at her core. She’s just figured out how to compensate; she’s constructed a constant, never-quite-convincing performance made up of baby voice and meek little smiles and lacy cardigans, snapped on a mask called Woman so that she can walk through the world unseen. I remembered identifying with Asami, but I forgot the moment when it started: The 43-minute mark, when we see her alone for the first time. She’s just hanging there, slumped on the floor in bare fluorescent light, like a deactivated robot, and in one awful minute we know: All of it was fake. Whoever we thought this woman was, that’s not who she is. She might not be a woman, or a person, at all. That quality of fakery, of letting your assigned gender hang off you like a cheap costume, is one I connected with intensely before my transition. I never asked myself why. Now I know.

The movie circles slowly through Asami’s lifetime of trauma, dissociating and free-associating and dissolving into surrealism as we slip into her point of view. The defining incident, her sexual abuse at the hands of her ballet teacher, is something we only see in a split-second flashback at the very end; the entire movie happens because of this, and “this” is something you can miss if you blink or reach for your popcorn.

What we know, though, is that Asami has spent her life performing for men. She’s performed “okay” and she’s performed “not raped” and she’s performed “not angry.” She’s created a person to be, the submissive old-fashioned girl of Aoyama’s and everyone else’s dreams. Her womanhood perfectly conforms to patriarchal expectations precisely because there’s none of her in it. She does not believe that her authentic self can ever be loved, and so, she has given up on authenticity — a soul death which makes her an “ideal” woman in a society where women’s inner lives always matter less than what men want to hear.

Aoyama falls in love with a fantasy rather than a person, but Asami has it worse; she has to be a fantasy, rather than a person. Her authentic self is so deeply buried that it can only be uncovered by seismic rage. Yet even in her fury, Asami can’t give up the burden of performance. Her cutesy, submissive, baby-voiced persona stays in place the whole time she’s ripping Aoyama apart; she says “you’re all the same” in the tone someone else would use to say “your table is ready, sir.” Even at her worst, she can’t help but be the nice girl men command her to be.

Then she lets go. By the end of the movie, we see Asami have an emotion that’s not connected to what anyone else wants or needs from her. We see the person behind the nice-girl mask, and she's finally happy. It’s not what Aoyama wants. He's not happy about it. But, provided your sympathies are in the right place, you will be. She deserves it; he deserves it; the world deserves to see Asami smile, bared teeth and all.

Audition is streaming on Tubi and Shudder.

At my other jobs, I wrote a piece on survivors' guilt and building resilience. I also published an essay I've been working on for a while now, about the Black trans second-wave feminist Pauli Murray – who has really been the only person getting me through this past month or so – and the trans legacy of the second-wave.

I genuinely can't write about Audition without getting the chorus of this stuck in my head. Now you have that problem, too.