Everyone Knew Neil Gaiman

A few thoughts on the difference between fans and friends.

I’m going to say something, here, and it’s going to sound like I think I’m special — but I don’t. I think what I’m about to say is probably more common than anyone knows. It’s this: I had a bad feeling about Neil Gaiman.

I never knew him. We had friends in common — everyone does, because everyone knows Neil Gaiman — but the most direct interaction I ever had with him was passing Hamish McKenzie’s email address through an intermediary. Substack wanted him on board, and he was supposedly going to demand they fix their transphobia before signing up. Once, in my capacity as a journalist, I asked Gaiman for a quote through his agent. I never heard back.

I doubt Neil Gaiman knew I existed. So it was crazy, being creeped out by him, but I was. He had that feel to him that certain people get after too much fame: Puffed-up and shiny around the edges, personality curdling into schtick. He was a little too pleased about all his celebrity connections, a little too happy to drop their names in every conversation. He was hostile to any interpretation of his work that wasn’t purely reverent; he didn’t want you to admire the writing, he wanted you to admire him, and he didn’t seem to recognize the difference. There was a subtle but pervasive sense of fakery to the man. You couldn’t say what he was lying about, but he was lying. You bit the coin, and it wasn’t gold.

Then again: What writer at Gaiman’s level of fame wouldn’t have an ego? Who can endure public scrutiny for decades without being fake? He knew so many people I respected, and they all liked him. He was an era-defining giant in a field where I was a nobody and a novice. The Substack thing — that wasn’t fake. It wasn’t a publicity stunt, because he didn’t tell anybody. Trans people trusted Neil Gaiman. Feminists trusted Neil Gaiman. All my friends trusted Neil Gaiman. My actual childhood hero was his best friend.

In order to trust my bad feeling, I would have to believe that every single one of those people had somehow missed signs that I, a total stranger, was picking up on. That did not seem reasonable. How did I know that what I felt wasn’t an inferiority complex, or envy, or parasocial attachment, or the ingrained paranoia of a survivor, or even the sting of rejection? How did I know the problem wasn’t me?

So, sure: His work often featured a certain kind of ethereal, free-spirit, manic-pixie-child-woman, and he surrounded himself with much younger people — typically fans of his work, typically women — who fit that profile. It was hard to pretend the fixation wasn’t sexual; he’d married one of them. Like Quentin Tarantino, another revered creator with non-specific creep vibes, he seemed to embrace “girl power” only insofar as it resembled his specific fetishes. He liked strong women, but only when he wanted to fuck them. It’s not an uncommon problem, but it rubbed up against my perception of him as a “feminist” and created friction. It just seemed to be very, very easy for fans who fit his taste profile to get access to him. It was much, much easier than it would have been with another author of his stature.

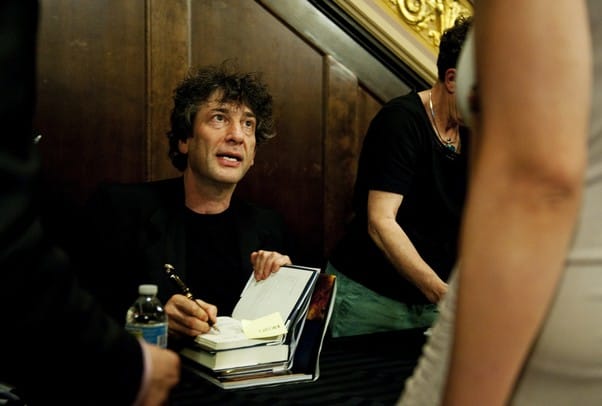

There was that — but what do you say to that? He’s friendly. He’s one of the most famously friendly men on the planet. The one thing everyone knows about Neil Gaiman is that everyone knows Neil Gaiman. Sure, there was probably some kind of mid-life crisis thing going on, but if those women didn’t want to sleep with him, they didn’t have to. No-one was making them, right?

Right????

Oh, right, the Internet said, when the rape allegations broke. Neil Gaiman and fans, Neil Gaiman and young women. We all heard about that. Everybody knew.