Eraserhead

On writer's block and being a gender traitor.

I was a feminist before I came out. I still am, but it’s gotten complicated. The narrative of my gender seemed pretty linear to me: I was a feminist because traditional gender roles made me uncomfortable. I transitioned because I figured out one source of that discomfort. Then word hit the Internet, and I learned that what looked like a logical evolution to me looked very different to everyone else:

I mean the 'decide you're trans after your Jezebel-era popularity wanes' is a pretty good grift

When your whole brand is about being a woman but then it stops cashing out so you do whatever the hell this is

When you fail at being a woman so hard you decide to transition into a man you don't get to comment anymore on feminism, femininity or motherhood. You canceled your membership dude

The majority of the time I've known about Doyle as an author, it was "Sady Doyle", obnoxious and very female feminist. Now "Jude Ellison Doyle" who IDs as male, but the whole thing feels very fake to me.

love those feminists who get so mad online they cut their tits off and try and become a guy

I also like how she opted out of being a woman but still wants people to acknowledge that she's oppressed, and has therefore twisted herself into a logic-pretzel and come up with "marginalized genders."

a trans man complaining about feminists kicking him out after he came out as a man. What did he expect for identifying with the enemy, a cookie?

She’s gonna kill herself. Or he’s gonna kill himself, whatever

Gonna start transitioning into a skeleton real soon.

These are comments from various right-wing message boards. They sound transphobic because they are transphobic, proudly and intentionally so. As such, it’s easy to dismiss them; after all, bigots say bigoted things. It’s kind of what they’re known for. In the rest of the world, things were trickier. No-one ever came out and said that I was a traitor, or that I had become “the enemy,” but especially in that first year, there were interactions — often with women; often with women I knew, worked with, trusted — that just felt wrong.

There’s such an unconscious chauvinism to how he imagines a woman’s experience of being in an all-male group, one woman complained. The experience I had “imagined” was something that had happened to me; the feelings I described were my own. I had said so in the piece she was talking about, so there was no chance of misunderstanding. It was an eerie feeling: my life — what I felt, what I feel, who I was, who I am or could be — had been deemed imaginary. Not as in, I made it up. As in, I was made up. I could no longer testify to what had happened, because I was not real.

Another one: I obliquely subtweeted my mother for being conflict-avoidant about my pronoun change. Cis women, triggered by a popular Internet advice columnist, also a cis woman, flooded my mentions, telling me you have no idea what it’s like for women, you have no idea how dangerous it is for us to disagree with a man, you are so big, so strong, so dominant, you’ve got no idea what danger is, none at all.

I knew the advice columnist. I knew that she knew I was trans. She and I had corresponded, before my transition, because we were both being threatened by the same men’s rights blogger — he had a history of doxing women or having them literally followed around their neighborhoods, and she wanted to commiserate. What she felt, watching dozens of her fans tell me I had no idea what it was like to experience misogyny, no idea what it was like to be threatened, none, is not something I ever found out. She must have soured on me; I don’t know why, so I can’t know for sure that it was my transition. As a good intersectional feminist, she’d probably be appalled at the idea. So would all of the good intersectional cis feminists who suddenly found reasons not to know me.

I decided to be fun; I decided to be flippant; I decided to joke about it, because if you can laugh at something, it can’t control you. I tweeted a sarcastic little thing about how living in two separate genders probably made me more qualified to talk about sexism, not less so. A woman who’d been reading my work for years wrote to me, enraged: How dare I say I had the authority to speak about women’s experiences, how dare I talk over women this way, what was wrong with me.

The obvious answer — that “women’s experiences” had been my experiences, until about five minutes ago; that I was still so early in my transition that most people took me for a woman on the street, so it was hard for me to even make any clear distinction — didn’t occur to her, and I didn’t know how to say it. I was a feminist, after all, and if a woman told me I was being sexist, I should probably just take her at her word.

For the record: I do try to take women at their word when they tell me there’s a problem with my behavior. I do know that transmasculine people can be misogynists — having written several thousand words on the subject, I won’t belabor the point here. That said, I think “Jude Doyle hates women” would be a pretty wild plot twist, given what I’ve spent the last fifteen years doing. I obviously believe what I believe, because what I believe isn’t tremendously popular, and many people hate me for it. Why would I lie in a way that made my life harder? If I were going to be dishonest, why not tell people what they want to hear? The same thing goes for transition: Even if I misrepresented my gender to my readers, why would I misrepresent it to my child, to my husband, to my mother, to Cleveland’s best top surgeon? There were no conceivable benefits to coming out as trans in a conservative rural area during the Trump administration; if I wanted to make quick money or be more widely liked, why would that be the route I chose?

This wasn’t about accountability. This was people tactically forgetting my entire life, including incidents from my life they had personally witnessed or been involved in, so that they could shame me for transitioning. It was bad for me to be a man; if I was a man, I was a bad man, I was all the worst things men are. I was hulking, I was threatening, I was predatory, I was violent. (I was about five foot seven if I stood up straight and wore shoes.) I suspect she’s capable of some kind of violent crime, one of the right-wing Redditors said; I was a monster, the Grendel in feminism’s mead hall, raging and endangering the cis women, and some hero had to pull out his sword and come take me down. Often, talk of my potential violence led to calls for violence against me:

[A dude] should kick this guy's ass and claim that it would be transphobic to not do so

About a decade ago, I was publicly raked over the coals by this nasty bitch. I am sexist, sexist, sexist, she announced. If she's a really man now, I'd relish the chance to kick her ass.

Ah, the life of the transmasculine feminist: From being beaten up by men to… being beaten up by men, I guess. Plus ça change.

What are you going to do, cry? asked one man, and it was true: I could cry. I could try to explain why I had a stake in the movement. I could point to my uterus, my continuing need for birth control and abortion, my history of being beaten and threatened and objectified and harassed and raped by men. I could say that my experience had not lined up with the average cis man’s. But to do all that, I would have to point out that I was trans. Which is to say: Not really a man. Which is to say: Faking, delusional, attention-hungry, lying, crazy. I would go from being all the worst things about men to being all the worst things about women. I was treated as both genders, but only the most monstrous stereotype of each one.

Because I was now a man, I could not speak about what it was like to be a woman. Because I had been a woman, I could never really speak about what it was like to be a man. Do the math: I could not speak. It was a double erasure, a double bind, in which every experience I had was false, and so nothing I said was credible. I could no longer derive authority from my experiences before transition, and shouldn’t even cite them — I had never “really” been a woman, so those things hadn’t happened — but those experiences could always be weaponized against me to prove I wasn’t “really” the man I claimed to be.

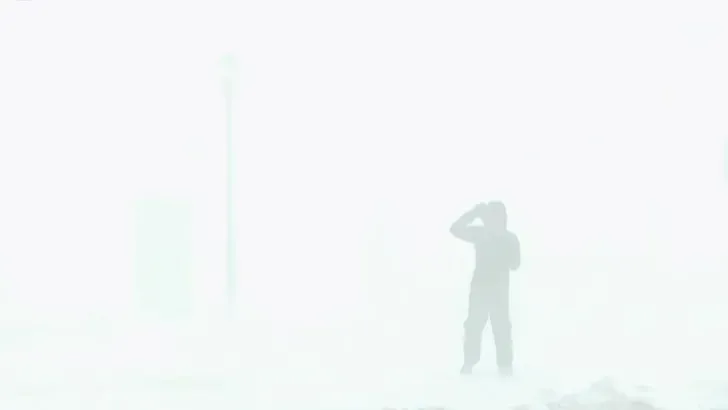

They call it erasure, when this happens. I wasn’t prepared for how literal the term was. Every day, I could feel myself disappear.

I began to have trouble writing after my transition. Argumentative writing, essay writing, requires both an “I” and a “you:” A person who speaks, and a person who is spoken to. You forge a self through language and communicate with the reader on the other side of the screen. Writing is a social act, and like all social acts, it involves gender: The way men speak to women is different than the way men speak to each other, and the way women speak to each other is different than the way men speak to other men. If you fuck up those codes, you sound rude or inappropriate or creepy. I didn’t think much about this, until it seemed I was always using the wrong voice to speak to the wrong people. I no longer knew who I was permitted to be, or what that person could say to whom.

It is not new to say that trans men occupy something of a blank space in the cultural imagination. Even well-meaning, trans-inclusive feminists can fall into it. Trans women are women: Oh, well, feminism is for women, they should be included. Trans men are men: Oh, well, men are the problem, let’s keep them out. To be perfectly clear: Including trans women is a good thing. Excluding trans men is a bad one. It isn’t “misandry” — which doesn’t exist — it’s a failure to grapple with the specifics. Trans men are men, but we are men who have been forced against our will to behave like women, who have (for our own safety, or from lack of perceived options) identified as women, who encounter violent prejudice every day of our lives based on the idea that we are women who refuse to carry out our assigned gender roles, and who have therefore been given the same poor treatment as women, in addition to the gender policing and general queerphobia we face for being trans.

If “man” and “woman” are opposed and mutually exclusive categories, if men can only ever be predators and women can only ever be prey, then trans men can’t exist. We are logically impossible under the terms of the current system. You either “treat us like men” by voiding out half our lives, or you write us back into womanhood by denying our male identities. I knew all that, at least in theory, but when I came out, I actually saw my life story disappearing into other people’s blind spots. I watched myself become unthinkable in real time.

How do you speak, when your “I” is a logic error? How do you communicate to someone who can’t believe you exist? There were days when I was not up to the challenge. There were other days when I made myself write, and everything I did came out false, grating, off-key in some way I couldn’t cure. I would catch myself posing, trying out publicly acceptable personae — Chivalrous Male Ally, Sassy Gay Friend, Unthreatening White Dad, Vulnerable Trans Person Explaining Why He Should Get To Live — instead of just sounding like myself.

I tried reading male feminists to get a handle on my new role. It didn’t work. All of them wrote as cis men, for cis men, with a kind of camp-counselor condescension: Hey, buddies, it hurts to hear this, but given that we’re unambiguously privileged by patriarchy and always have been, we owe it to our wives and mothers to give the ladies a hand. The idea that I had always occupied a privileged position within patriarchy was, frankly, untrue; nor did it seem to me that a trans person was any less gender-marginalized than your average cis woman. What privilege I had was conditional, and these books were no guide. Men who wanted to “forge a positive masculinity” (and everyone was very clear that I needed one of those) were encouraged to get in touch with their “feminine sides.” Maybe that was healthy for cis guys, but I had been forced to do feminine things, and present in feminine ways, for the entirety of my young life. Whatever liberation I had achieved came from giving myself permission to stop.

Cis male feminists didn’t make any more room for me than cis female ones. Whatever truths I had were trans. Here's where I tell you that my experiences are not remotely unusual or incoherent by trans standards. All I have to do is open a book by a trans guy to find them. Elliot Page’s memoir, which I finally picked up last week, is back-to-front sexual assault and harassment. Ponyboy, the novel I’m reading now, has the narrator worrying that he could get pregnant after a sexual assault. Any given memoir or novel by a trans guy contains at least one account of being preyed on or discriminated against. If I pause my self-pitying essay about how no-one understands me for five seconds, I can typically find someone making the exact same points in a tweet. Look, here they are now:

Realized through this thread that I already wrote a little bit about this in the first issue of Puddletown Masc. pic.twitter.com/PlxPyqyScT

— Bitter Tea Tor (@write_tor) January 31, 2024

TRANS TWITTER DISCLAIMER: I do not know the writer or know if anyone has beef with them. The post literally just surfaced in my feed while I was writing this.

My experiences of gender are complicated, but no more so than many queer people’s: I am non-binary. I really do feel connected to womanhood in some important ways, and traditional masculinity doesn’t work for me. It’s just that I am far more physically comfortable in a body that looks and presents male; “man” isn’t the whole truth, but it’s a respectful and concise way to acknowledge it, and it’s also increasingly what people guess when they look at me. My Trans Twink era ended long ago, if it ever started; I have stubble and a deep voice and more chest hair than my husband. I once carried on a full conversation in a swimming pool, with my shirt off, with a man twice my age, and he still said “he” when he introduced me to his wife.

That said, he also made a point of telling me that his brother was gay, and that he was fine with it. People often do that to me when they’re being friendly. They look at me and see man-but-queer, or man-with-a-difference, and that’s what I am: Man with a queer difference, man who is trans. For trans men, what I’ve described — the complicated attachment to womanhood, the failure to find a voice for your experiences in feminism, the being read as either male-but-not-masculine or masculine-but-not-male — is so common as to be cliche.

What I am is simple. Old guys in swimming pools can wrap their heads around it. The problem happens when I try to write it down: All of a sudden, concepts that seem perfectly clear and obvious to me become opaque and impossible to communicate to anyone else. I tell you the sky is blue; you ask me to provide a scientific defense of my frankly unproven and dangerous assertion that skies have color. Is there even such a thing as sky? As blue? As me? There can’t be, right? I fall silent, because a person who can’t exist can’t argue.

When I have trouble writing, these days, it’s not because I have nothing to say. It’s because I can’t imagine a person who is willing to hear me. I can’t foresee anything but hostility coming from the other side of the screen.

“We’ve discovered an audience hungry for ideas that don’t fall into ideologically neat buckets, and which challenge the status quo on both sides of the political aisle,” says the press release. “Our goal with Thesis is to carve out a dedicated space for these books, and to move the conversation forward around the pressing social issues of our time.”

This is a statement from the heads of Thesis, an imprint of Penguin Random House, which will be publishing Jesse Singal’s forthcoming book on youth transition. “There's a big need right now for writers who make counter-consensus arguments without falling into reflexive contrarianism,” says another Thesis-head. “I’m excited for Thesis to publish those thinkers who can stand outside the currents of the moment and help us see and think differently.”

Readers already know Jesse Singal’s thoughts on youth transition, and on trans kids: He doesn’t like them. He wants less of them. His entire career has been dedicated to a crusade against their medical care. How this “challenges the status quo” of a country where one of the two major political parties ceaselessly reviles trans people, or how it “stands outside the current moment,” a moment when 22 states have enacted bans on gender-affirming care for minors, and over a hundred more bans are being advanced in state legislatures, is not explained. It doesn’t have to be. What matters is “moving the conversation forward” toward its intended outcome: More dead and immiserated trans kids.

Here is the counterbalance to all that writer’s block and self-protective silence, the reason to keep swinging and missing: If you don’t speak, someone will speak for you. Trans people may rip ourselves apart or drive ourselves mad trying to communicate our existence in some well-reasoned and responsible way, but cis people have no such compunctions. Cis people never stop talking about trans people, because they never have to; cis people can just make shit up, and someone will pay to publish it, pretty much every time. That’s what unconditional privilege in patriarchy looks like. It is the freedom to define someone else’s reality on your own terms.

Trans people, historically, have a difficult relationship with first-hand testimony. Until very recently, we could only transition by convincing medical professionals we were “really” trans, and we did this by making sure to tell the only story our doctors wanted to hear. Something like: I’ve always known I was a boy. I only played with boys’ toys growing up. I always feel like a man — not a faggot or a sissy or a feminist white knight, a real man, the kind of man all men should be. I hate my genitals. I would never consider getting pregnant. I want to work a man’s job. I want to use power tools and know about football. I want to be a breadwinner and never see my children. I’m only attracted to women. During sex, I like to penetrate women. I never get penetrated, by anyone, and I certainly never penetrate any other men.

This isn’t every trans person’s story. This isn’t any trans person’s story. This is a cis story, created by cis people, and every trans person I’ve ever met has some detail of their biography that contradicts the narrative. Yet instead of concluding that their story is wrong, gatekeepers conclude that trans people are wrong — unless we fit the absolute most stereotypical idea of our gender, in every way, we’re imagining things. This is the trans testimony trap: In order to be believed, we have to be dishonest. We have to lie about our lives, or at least edit them substantially, in order to be the kind of trans person the world can comprehend.

That old narrative still exerts its pressure; I still find myself bluffing in order to fit it better, or shying away from the wrong kind of disclosure. Yet the ultimate goal of this gatekeeping was not to make trans people real — it was to make us invisible. Under this system, only the most cis-passing trans people were given care, and in order to receive it, they usually had to agree to erase themselves: Cut off their family and friends, move to a different town under a new name, start a new life, and tell no-one in that new life that they were trans. The goal was to make it impossible to tell us apart from the cis population. In order to do that, our past selves had to disappear.

When we could not speak, we could not find each other. When we could not speak, we could not organize. When we could not speak, cis people could go on pretending we didn’t exist, or that we couldn’t exist, and that was what most cis people preferred.

Depriving people of their life stories is a form of violence. When we can’t draw authority from our own experiences, we are all the more open to being defined by the oppressor. Everything that happened to me happened to the same person; if that person’s life and identity don’t make sense, well, you might be asking the wrong questions. My truths are not cis truths. My life is not a cis life. My life is not every trans life, either. It’s just mine.

When I write these days, I try to remind myself that whatever I’m afraid of saying is already true, and denial will not change it. I remind myself that the wrong people benefit from my silence, and will use it to write a version of my life I can’t recognize, or just write me out of the world. There is no established story or role for me; I belong to a category the world is still learning to imagine. I cannot account for the world as other people imagine it. I cannot give you every man’s story, every trans man’s story, every trans person’s story; I don't know them. What I do know is that every new story helps map the territory. All I can do for you, from where I'm standing, is tell you how things are.