Broken Watch

"Watchmen," and what happens when a work designed to upturn cliches becomes one.

Before ye may pass unto the essay, consider ye these book announcements three:

Be Not Afraid, my new horror comic series with Lisandro Estherren, starts June 4. Please read this interview, then pre-order it at your comic shop.

My non-fiction book DILF: Did I Leave Feminism is due out in October. You can pre-order that everywhere, but the way to support your local bookshop is Bookshop.org.

I wrote some superheroes (and a very trans villain) for this year's DC Pride.

It is rare, these days, to find anything that gives me simple and unmitigated pleasure. The thing that’s been doing it lately is Elizabeth Sandifer’s Last War in Albion.

Some readers of this newsletter might know Last War from its least essential portion — a 60,000-word analysis of Neil Gaiman’s descent from pathologically ambitious young fantasy writer to fame-bloated rapist hack — which recently went viral. What you might not know (or be prepared to appreciate, given that 60,000 words is already longer than many books) is that the Gaiman segment was essentially a footnote to a much longer, more complicated work — an analysis of the careers of Grant Morrison and Alan Moore through the lens of their lifelong rivalry and mutual belief in magick (the Aleister Crowley kind, spelled with a K).

Sandifer pretty convincingly places both Morrison and Moore in a tradition of British visionary writing that stretches back to William Blake — who got chased out of his house by ghosts, was once found naked in his garden re-enacting the Fall of Eden, and who did, after all, both write and illustrate his massively complicated personal mythos, in a precursor to present-day comics. These are all writers with deep spiritual convictions, albeit ones that many people dismiss as eccentric, and they are also people with radical left politics, and they aim to convey both things through their work.

Last War in Albion is one of those huge, obsessive labors of fannish love that used to be common on the old Internet (for those who remember Cleolinda’s novel-length analysis of the Twilight series on LiveJournal — we salute you) but which feels increasingly rare these days. It is explicitly and intentionally not for everyone. But if you care about the subject, Last War is a huge structure that you can happily get lost in. I am probably less than halfway into it, and I am already firmly convinced of two things:

(1) Alan Moore is a genius. His impact on both comics and pop culture is like the curvature of the Earth — so massive that you actually can’t see it.

(2) Alan Moore is directly, personally responsible for 99% of the genre tropes I despise.

These two claims do not contradict each other. Every comic-book writer is influenced by Alan Moore, whether they’ve read him or not. The basic furniture of a “serious” comic — captions instead of thought bubbles, minimizing or eliminating sound effects — is all stuff that we do because Alan Moore once did it. The idea of a “serious comic” is something we have because Alan Moore once had it; yes, there were other important figures, before him and after him, but he took it mainstream and made it sing.

It’s also true that the real engine of Moore’s greatness — his meticulous formalism and dazzling layers of allusion — is something that the vast majority of writers cannot manage. Since most people cannot write like Alan Moore (and shouldn’t try to) the things that are “influenced” by him often wind up lazily copping certain tropes and aesthetics, without having anything new to say about them. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Moore’s defining work, the one so central Sandifer devotes a whole volume to it: Watchmen.

That Watchmen is still relevant today, nearly forty years after its first publication, I need hardly tell you. It continues to generate new properties: Damon Lindelof made a well-received Watchmen TV series in 2019. DC published a Watchmen crossover, Doomsday Clock, in 2017. We will not be discussing the Zack Snyder movie — in order to do that, I would need to see it, and I never plan to — except to say that it, too, exists, and that Alan Moore hates it. Alan Moore hates everything, which will be important later, but this is one of the rare cases where he shares the majority opinion.

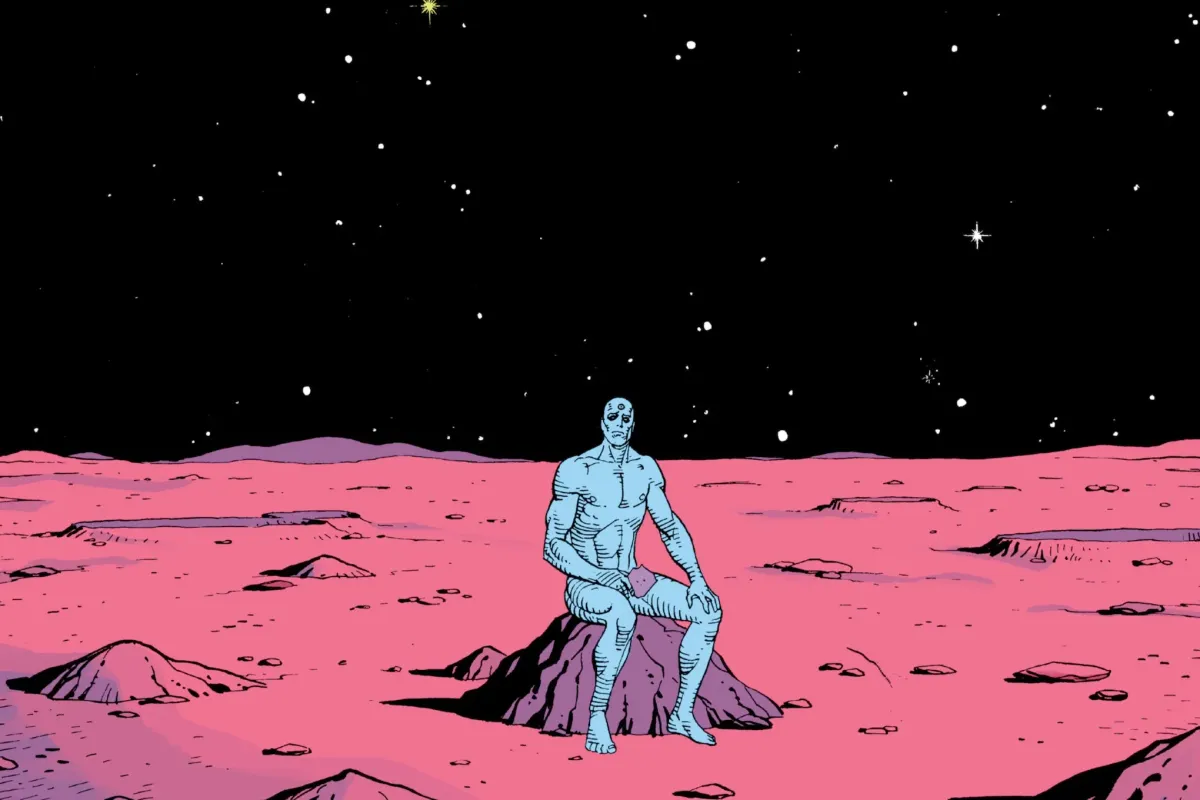

More than that, though, Watchmen is baked into the language of the Internet. It’s the source code for countless memes: “I’m not locked in here with you, you’re locked in here with me.” The Pagliacci joke. Dr. Manhattan blocks a weird guy in your mentions. Dr. Manhattan reacts to celebrity news. The specific tone and timbre of Watchmen — grim, cynical, prone to seeing fascism under every display of all-American patriotism and genocidal bloodlust under the patina of liberal good intentions — is very close to the voice you need to adopt if you want to be a hit on, let’s say, Twitter.

Whether it is a good thing that so many posters identify with Dr. Manhattan — the brilliant, prescient, omnipotent, indestructible, copiously bemuscled Chad of a man who does absolutely nothing to stop the world from ending, aside from complain about his boredom and (like it says on the tin) watch it happen — is debatable. The world thinks in Watchmen, or at least a specific highly online subset of it does. That’s the point.

So I don’t have to recap its plot, except to say that it is an extremely pessimistic answer to the question “what would ‘real’ superheroes be like” — they would be serial killers; they would be sexual fetishists; they would be Klan-style vigilantes; they would, at best, be gods, and like God, they would sit back and watch things happen — which is also a dazzling work of literary criticism aimed at the superhero genre. The idea that superheroes are closeted queers reflects the 1950 pro-censor jeremiad Seduction of the Innocent; the superheroes who get turned on by their costumes evoke the spectacularly transparent kinkiness of Wonder Woman creator William Moulton Marston; Dr. Manhattan is a Jewish immigrant just like Superman and/or his creators; Rorschach’s fascist violence satirizes the far-right politics of industry legend Steve Ditko; etc. The more you know about comics, the more you know about Watchmen, and vice versa.

By now, though, you are starting to recognize what else Watchmen is, or what it inadvertently gave rise to: A Dark And Gritty Take On, a cliche bemoaned by approximately every critic in existence for the past ten years. You take an existing genre, smear some dirt on it, add some torture and/or sexual assault, and boom! It’s now serious art. We have Dark And Gritty Takes On Space Opera (Battlestar Galactica, The Expanse) and Dark And Gritty Takes On High Fantasy (Game of Thrones) and Dark And Gritty Takes on Archie Comics (Riverdale), and, of course, we have Dark And Gritty Takes on Superheroes. And Dark and Gritty Takes on Superheroes. And Dark And Gritty Takes on Superheroes. And Dark and Gritty Takes on Anne of Green Gables, and The Wizard of Oz, and Kevin Can Wait, and I actually liked that last one. And Dark and Gritty Takes on Superheroes, again.

It’s a general rule of the DGTO that the first one you see — for me, it was Battlestar Galactica — feels revelatory. Here is the genre you’ve always loved, with its artifice simultaneously exposed and redeemed, given the dignity of true art and the relevance of cutting social commentary. It gives self-conscious consumers permission to enjoy genre entertainment by making it “adult” and “literary,” while also indulging the most juvenile fantasy of all — the desire to know what it would be really like to live inside the fictional universe in question.

It works. But it's a formula with diminishing returns. Each new DGTO you see will get less and less impressive, as the approach slowly reveals itself to be, not a radical re-envisioning of the medium, but a grab-bag of reliable tricks: Shaky-cam. Brownish color palettes. Torture scenes. Nudity. Major characters die, often. Everyone wears gray costumes.

Rape, and specifically graphic rape scenes as a de facto signifier of “seriousness” — that’s the DGTO in action, and that’s Watchmen, too.

Rape is an Alan Moore specialty. It’s probably the most criticized facet of his work, and for good reason; the same pen that wrote Watchmen also gave us the career nadir of Neonomicon, an entire comic written for the purposes of delivering a lengthy gang-rape scene with a Lovecraftian fish-man who is known for his enormous dick and massive, splattery cum shots. It truly does not help that Moore so obviously scripts these things one-handed, and they’re likely to be re-evaluated in a much harsher light, given his long-standing friendship with Neil Gaiman. They probably should be.

Nonetheless, rape was used in Watchmen to genuinely shocking effect. Comics really were widely dismissed as children’s entertainment, at the time, and depicting something as horrific and distinctly R-rated as one superhero raping another was a loss of innocence for the genre, a ripping away of the protective membrane between superheroes and our real world. The rape scene was not “good” in the sense of being morally admirable, or fun to read, but it earned its inclusion by accomplishing a specific and necessary function.

So there really was a moment — a moment that came and went when I was three years old, and many readers of this newsletter were not born yet — when you could justify including a rape scene in your comic just to be shocking. But then everybody read Watchmen. The guys who liked Watchmen put rape scenes in their own far less interesting comics, to emulate Watchmen, and the guys who read those less interesting comics put more rape scenes in their comics, to emulate the guys emulating Watchmen, and the guys who read those guys — because this is, overwhelmingly, a history of guys we’re talking about — grew up to write novels, or direct movies, or run TV shows, or just generally be Zack Snyder, and all of them put rape scenes in their movies and TV shows and novels, less because they had any specific point to make than because that’s just what a “serious” genre work was expected to do.

And the end result, thirty-nine years and four months after Watchmen, is that I get a news alert on my computer that Andor (the Dark and Gritty Take On Star Wars) has a sexual assault scene in it, and instead of having any kind of emotional reaction, I just roll my eyes and think, of course it does.

Now: Everyone I know loves Andor. Maybe, one day, I will watch Andor and love it, too. If the Andor rape scene resonated for you, great — the episodes of Battlestar Galactica that dealt with rape as a weapon of war resonated for me, and were (at the time) some of the most deeply moving things I’d seen on television. It’s just that all the other rape scenes, in all the other DGTOs, have taken the shine off. In 2025, rape registers less as a crime against humanity than as one more reliable trick, one more trope you can wedge into your genre show to prove that it’s for grown-ups. It doesn’t feel shocking, or transgressive, or offensive; it feels de rigeur.

The thing is: I don’t need Star Wars to be serious. I truly don’t. No part of me has ever yearned for a psychologically acute portrayal of rape trauma from a fictional universe that contains Jar-Jar Binks, “jizz music,” and (I’m assuming) a little robot called, like, B00-B5 who communicates in ‘90s pager noises. I hear “rape scene on Andor” and I am not horrified, I am not enlightened, I am not donating to Amnesty International nor am I calling my Congressman to demand censorship of our prestige space shows: I am just imagining a solemn monologue by a guy named Boppo Weedo that goes “Rape is an eternal consequence of armed conflict, used to break the enemy’s spirit and literally invade the bodies of a conquered people! Perhaps we should relinquish patriarchal and phallocentric narratives of martial bravery to acknowledge instead the toll of sexual violence. What do you think, B00-B5?” “[SAD BEEP.]”

It all just feels kind of stupid, is my point here, and it shouldn’t. I don’t want to have a “been there, done that” reaction to sexual trauma. I would like it to matter, every single time. So why do we keep drawing from this well, almost forty years after it was drilled and drained? How does one specific superhero comic define our language of “seriousness,” and why do we let it? How do we get out of the shadow of Manhattan?

[SAD BEEP,] reader. [SAD BEEP] indeed.

Some time after I started reading Sandifer, I picked up a book by Rita Felski called The Limits of Critique. Felski writes that critique — reading a text against itself, picking it apart to uncover its sinister hidden messages and complicity with oppressive structures; performing what Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick and/or the queer Internet calls a “paranoid reading” — has come to be the default mode of seriousness or intelligence in literary criticism. Rather than representing a specific viewpoint, it represents the only intelligent viewpoint. Rather than representing a particular mood or set of priorities, it represents Truth Itself.

Watchmen is nothing if not a magnificently paranoid reading, an era-defining critique that picks its own form and genre and plot and characters apart even as it creates them. Watchmen is not, in fact, a tremendously “realistic” work — again, I hate to spoil this, but an omnipotent indestructible man hangs out on Mars for large portions of the action — but it has the seriousness we instinctively accord to critique, and shares our assumption that the most cynical answers are necessarily the truest. (Put another way: Watchmen is not pessimistic because it is “real,” it feels real because it is pessimistic.) The text invites and performs a hostile reading of itself, like a man performing his own triple bypass surgery live on stage.

It is a tremendous performance. Watchmen smacked the crap out of me when I first read it, and it still packs a punch. But Moore’s deconstruction has been lazily undertaken, over and over, until it has itself become the formula in need of deconstructing. A work purposefully designed to upend cliches has become a cliche, and nothing has come to take its place.

“The danger that shadows suspicious interpretation, I propose, is less its murderous brutality than its potential banality,” Felski writes. “For several decades, it has served as a default option[.]" When a genre based on subversion and shock loses its ability to shock us, it no longer has anything to offer: “It no longer tells us what we do not know,” writes Felski, and thus “singularly fails to surprise.”

High-culture or academic critique has become more and more unnecessary, as the approach leaks out into the culture and provides us with an endless array of self-deconstructing artworks. What I will begrudgingly call “SJW” criticism — the identity-politics-centered takedowns of pop culture that used to be popular on Tumblr; the engagement-generating gimmick of reading a famously problematic text in order to live-tweet all the ways it is problematic — partakes of critique, and even calls itself that sometimes. A Song of Ice and Fire is a critique of Tolkien; Battlestar Galactica is a critique of Ron Moore’s own work on Deep Space Nine. The boom in puzzle-box narratives (of the sort pioneered by, say, Damon Lindelof) and online fan theorizing dedicated to picking up each puzzle's “hidden” messages is a depoliticized version of hostile reading – you consume these things, not to enjoy the plot or the characters, but to beat the show.

The goal of reading something is to uncover the reasons people shouldn’t read it. The goal of watching television is to be smarter than the television show you’re watching. The goal of telling a story about superheroes is to show us how fucked-up it would be if there were superheroes — over and over and over, long after the point has been made.

There is a word for this kind of thing: Magick. The Aleister Crowley kind, with a K. Alan Moore does practice it, and he’s apparently very good. One of its key tenets is that our worldviews, themselves, are magical — they determine how we think, and thus, determine what we do. The person who controls how we think controls us.

The true goal of the most powerful magicians, writes 19th-century occultist Eliphas Levi, is to “originate a current of ideas which produces faith and draws a large number of wills in a given circle of active manifestation” — to create a belief, and thus, turn everyone who shares it into his servant, “like a whirlpool which sucks down and absorbs all.” There are three ways to effect this: Through symbols (the Christian cross, the Pride flag, the hammer and sickle, the Golden Arches), through physical gatherings (political rallies, Catholic masses, fish-guy gang-bangs, AA meetings) or, most insidious of all, through language.

Simply put together a story so compelling that people repeat it, share it, imitate it, think in its terms, and you change the world. You rule the world. You remake the world in your image: “We are on the verge of fulfilling the intentions of the man whose sayings we repeat,” writes Levi. Think about that the next time you post that reaction image of Dr. Manhattan.

Watchmen is powerful magic. It changed how we thought, and thus changed what we did, for four decades and counting. But in a time of actual rising fascism targeting my community, I am less and less convinced that cynicism and despair are any kind of solution — we all know how bad things are, but if we sit on rocks and sigh about our ennui, they will surely kill us. We need to tell the stories that help us move.

The good news is that it is precisely not Watchmen’s paranoia or cynicism that make it brilliant. It’s the formal intelligence — the tremendous, page-by-page, line-by-line level of attention to detail and form and craft, to making a comic that works.

My favorite issue of Watchmen is “Watchmaker,” the Dr.-Manhattan-on-Mars installment, because Dr. Manhattan’s atomically fragmented perspective — he perceives every instant of time happening simultaneously, with no ability to alter it — is not just a commentary on God, or Superman, or the nuclear bomb (though it is all those things) but an invitation to consider the atomic unit of a comic book: The panel. Every panel depicts a frozen moment in time. They all exist simultaneously, and they are inalterable — you can flip forward or backward, read them in any order, lay the pages out on the floor and see them all at once, and they never change. It is only their particular arrangement in space, and our mutual agreement to read the panels in a certain order, that gives us the impression of linear time passing. We’re not being invited to understand Dr. Manhattan, but to become him; to unhitch ourselves from the lie of sequential imagery and view Watchmen as it really is, a collection of still images happening all at once.

“Watchmaker” is a comic book that wants to show you what a comic book is — it wants you to examine the object in your hands and truly see it, perhaps for the first time. That kind of rapturous, granular attention does not spring from hate or cynicism. People do not spend their whole lives becoming experts in a medium they despise. It comes from love.

Cynicism and darkness can be just as adolescent and hacky as anything else — just look at all those teenagers and teenage-brained adults on Reddit, posting about how fashy old Rorschach is the “literal coolest thing ever.” It’s the ability to make something truly new, to help us see the world with new eyes, that is the real gift. If we’ve learned anything, over the past thirty-nine years, it’s that anyone can take a watch apart to see how it works. The trick is to put it back together again — all those moving parts, in just the right order, pointing at our exact moment. Listen: It’s still ticking.

Watchmen is on sale wherever you buy books. Also, it's literally everywhere. I really like Promethea, but that's beside the point.

Here's that Be Not Afraid interview again, if you're interested.