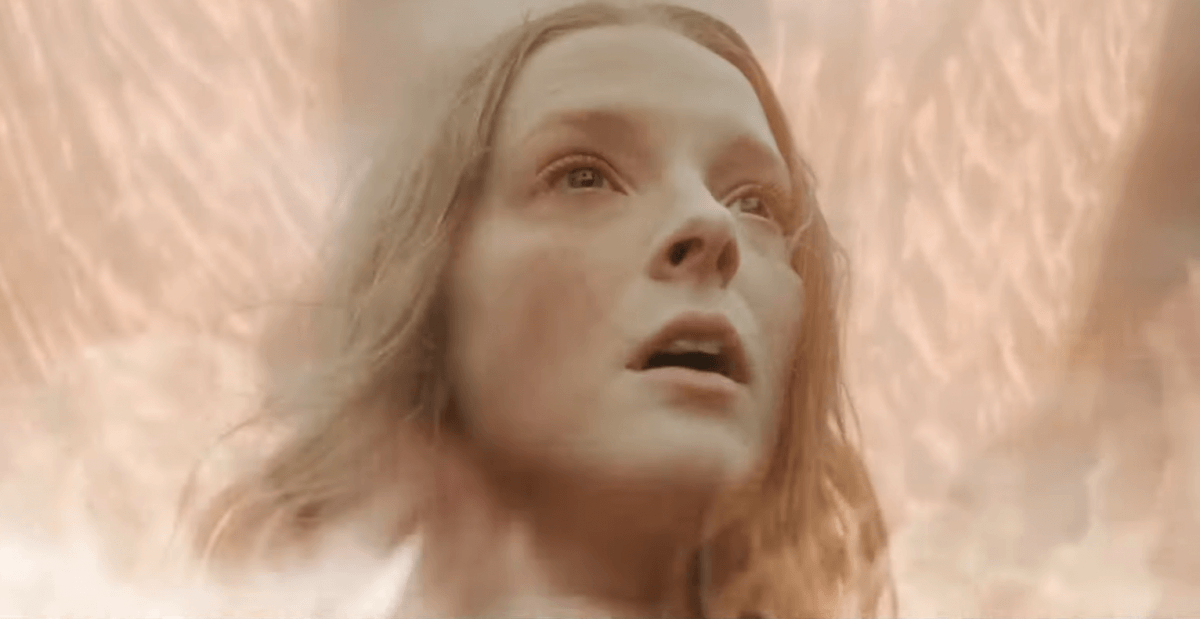

A Deal with God: Saint Maud (Rose Glass, 2021) / mother! (Darren Aronofsky, 2017)

Do you want to know that it doesn't hurt me?

Welcome back to the newsletter! This month's theme is THE GOOD ONES.

MAW, my comic with A.L. Kaplan, is entering its last stretch; the deadine to pre-0rder its final (!) issue at your comic shop is this Monday, December 13. Issue #4 will be out 12/22. You can read the first five pages here.

As always, I owe every opportunity I get – particularly MAW, which is the most fun I've had in ages – to you. Thank you for buying, supporting and recommending my work.

I wanted to be a saint, before I wanted to be anything. Mostly, what I wanted was a way out of the world.

Nothing about living appealed to me, as a child; people were cruel and small-minded. Suburban Ohio in the 1980s was a wasteland of chain restaurants and big box stores. We were comfortable — it was a time when a part-time office worker and a grocery store clerk could buy a house in a good school district — but I didn’t understand that yet. Comfort was not the same as joy.

This is the sort of thing you can settle for, if you believe it’s the only world available, but I went to church, so I knew I had options. There was another world, one of total Goodness, where everyone was exceptional and everything was perfect. It was where you’d go after you died. God lived in that world, and he controlled who got in there, and the only people he admitted right away, without a purgatorial waiting period, were the saints.

My first idea was to become a priest. That would be the easiest way to go about it. It was good work, praying full-time, interpreting divine wisdom for people with more earthly priorities — I wouldn’t have to get married, which already felt very important to me, and I could spend all my time on God, purifying myself, learning how to meet his exacting standards.

There were obstacles to me being a priest, though. These obstacles were obvious to everyone but me. I was furious when I found out — how could God not like me? He was supposed to be better than ordinary people, kinder, wiser, that was the entire point — but anger quickly turned into bargaining, and I decided that God had set me a more difficult path because he wanted something special from me.

I could not be a priest. That was too common, too easy. I had to be the kind of believer God loved most of all. I had to be a martyr.

Saint Maud is a movie about martyrdom — a furious, almost spiteful clinging to holiness, one which is motivated not so much by love of the divine as by distaste for the world. It’s a slow-burn horror in the A24 mode, which is to say, nothing happens until everything happens at once. The movie’s main scare lands about 0.3 seconds before the closing credits. It’s worth the wait, though, so let’s dive in.

Maud, when we meet her, is a palliative care nurse. She used to work at a hospital, where a patient seemingly died very badly under her care. She used to have a name that wasn’t “Maud.” Now she’s a freshly converted Catholic and a private nurse, working in the home of a retired dancer with terminal cancer, and providing us with updates on all of it through a constant monologue addressed to God.

Maud’s client, Amanda, is a mean-tempered hedonist. She’s also into girls. Both of these facts inspire intense attention from Maud; the way she examines old posters and videos of Amanda’s body is both judgmental and covetous. Maud needs to be special to this woman, an important figure in the story of her life, and it’s not long before she is trying to save Amanda’s soul with stories about what “God’s presence” feels like.

It feels like an orgasm. This is not unique, in the history of sainthood, but it does cast a certain light on Maud’s need to share God with Amanda — and on her fury when it turns out that Amanda’s interest in God, or Maud, has not made her stop hiring sex workers. Amanda mocks Maud’s faith; Maud slaps her; soon, Maud is off on her own, with only God’s company to console her, and the things God wants from Maud get more disturbing over time.

Maud is an intensely unlikable protagonist — homophobic, repressed, prudish, self-righteous, with a timid church-mouse demeanor that somehow makes her arrogance all the more obvious. We instinctively recoil from her, partly because we know she would find some way to hate us if we met her. Yet Maud’s hatred of the world is earned. We see who Maud is when she doesn’t have God to define her, and it’s grim. There are guys who are bad in bed, and guys who are worse than bad. There are bars where she doesn’t know anybody, and work friends who don’t have time to catch up. “You must be the loneliest girl I’ve ever met,” Amanda says — it might be the only nice thing Amanda says — and it’s true. Maud is floating off into heaven because she has nothing to hold her to the world.

Putting (let’s say) nails in your shoes might hurt, but it hurts spectacularly. It’s a big, meaningful sacrifice, one that Maud makes intentionally. The dirty bedpans and date rapes hurt worse, because they have no purpose. Maud’s greeting to strangers is “may God never waste your pain.” This suggests that pain is inevitable, but waste isn’t. Maud has stopped hoping for happiness, and now, she just wants her agony to be the one she chose.

I like Darren Aronofsky. I’ve probably watched Black Swan more than any other horror movie of the 2010s. He also reportedly read my first book, Trainwreck, and I’m told he did this when he was dating Jennifer Lawrence and making mother!, so I’m partial to the movie. I feel like part of me was on set.

Moreover, I just like mother! as a work of horror. It’s a scary movie, although it clearly wants to be more than scary. It has its own distinct ideas about what’s frightening — being overwhelmed, being invaded, being flooded with stimuli; time speeding out of control, events proceeding past the point of no return — which don’t rely on shocks or gore, and are instead pretty close to an actual nightmare or panic attack.

This is not what will make or break mother! for the average viewer, though. It’s going to come down to two things. First, whether the movie’s high concept — “the Bible, as told from Mother Nature’s point of view” — strikes you as pretentious. Second, whether you are willing to see the crucifixion of Christ presented as a bunch of depraved partygoers ripping apart and eating a newborn baby.

Personally, I find the concept enjoyably Tori-Amos-y, but I skip the baby-eating. We all have triggers, child death being one of mine, and thanks to the wonders of home video, no-one really has to watch anything. Moreover, focusing too much on that one scene — as nearly everyone does; blasphemy and dead babies are shocking, more so when you combine them — distracts you from what the movie is trying to do overall.

We begin with a big, booming, deep-voiced man (Javier Bardem) and his wife, who is cartoonishly, almost simple-mindedly angelic (Jennifer Lawrence, whose perfectly smooth Renaissance-cherub face is a load-bearing structure here). The husband spends all his time writing a supposedly very important book. The wife is perfectly contented and domestic, spending all her time making their home “a paradise.” Neither of them have names, but you already know their names, just like you know which book the Father is writing.

Then the Father invites a man to stay with them. The man brings his wife. The wife brings her two sons, one of whom kills the other. Then there are more people, and more people, and more and more and more people, until there are riots and war zones and raves and human trafficking all taking place in this one house, which is being burnt and torn apart and ripped to shit, and the Mother is pregnant and giving birth, and there is nowhere safe for her to go, because every second there are more and more and more and more and more and more and more people.

Eating her baby sure does cheer them up, though! So does beating her and spitting on her and calling her a bitch and a whore when she objects in any way to having her paradise damaged. This isn’t a subtle metaphor; the movie, as a whole, is not remotely subtle. But taste is the enemy of excess, and mother! works best if you let it overwhelm you.

mother!’s gender politics — men = culture, women = nature; men = exploiters, women = exploited — aren’t complex. If you take Lawrence’s character as anything other than an allegory, she’s a sexist idea of what “good” women are; both Mother Earth and Mother Mary, virgin and mommy, with no trace of agency to her sainthood. Michelle Pfeiffer, as Eve, fully eats Lawrence’s lunch on multiple occasions — she plays innocent, scheming, irritating, mournful, worldly-wise, maternal, evil, seductive and betrayed, sometimes all in one scene — in part because she represents all the flaws of humanity, and interesting characters need flaws.

Yet the movie ends in the same place Saint Maud does: To be a “good” woman is to immolate oneself. Or maybe self-immolation is preferable to being a “good” woman in this world. Both Mother and Maud arrive at martyrdom, though the Mother is martyred in defiance of God and Maud is martyred in his service. In both cases, though, God is less of a deciding vote than you’d think. Their apotheosis feels less like divine commandment and more like the fullest possible expression of their rage.

There are so many girl martyrs in the Catholic canon. It’s the main thing a girl under eighteen can be. St. Lucy carved out her eyes because a suitor complimented them, and St. Agatha cut off her breasts. St. Agnes — patron saint of all girls — was dragged through the streets naked, then burned, then beheaded. St. Joan died at the stake. I liked Joan best, because she cut her hair off and wore men’s clothes, and God spoke directly to her. She still had to die, but some part of her refused the female mandate; her heart didn’t burn.

I couldn’t cut off my breasts, or even my hair, but I found ways to burn. I put matches and lighters to my skin. I stuck myself with needles and safety pins. I wanted a hair shirt, but settled on wearing an uncomfortable sweater under my other clothes. I filled a tub with near-boiling water and got in it. When I stood up, I passed out on the bathroom floor. That’s when I had to explain to my mother what I’d been doing.

She was gobsmacked. What nine-year-old wants a hair shirt? Whose fourth-grade career goal is to die a martyr? God wouldn’t let me in any other way, I told her. Almost no-one made it into heaven. Everyone went to purgatory. Everyone sinned before they died. I couldn’t let myself be “everyone.” I’d boil myself alive before I let myself fall short of God’s glory. I’d burn; I’d bleed; I’d die.

I eventually found worse reasons to do all those things. Women are expected to do them; not for God, but for Greg, who took them to prom and bought a case of Natty Ice to drink in his rec room. Male sacrifice is spectacular and glorious. You can use it for something. You can offer it to country, to cause, to God. Female sacrifice is daily and mandatory. It’s dirty diapers and dirty dishes and mac and cheese spooned onto plates at exactly five-thirty every evening. It’s continually moving your own wants and needs and plans – your own you – out of the way so someone else can be satisfied.

I don't know if I believe in Heaven any more. I believe in Hell, though, and that's what it looks like. As a child, I already knew that I didn’t want to waste my capacity for misery on some guy with bad breath and holes in his socks and a favorite football team. My suffering was reserved for the big guy, the man in charge; I wouldn't give it up for anyone but God. I wanted my pain to matter; I wanted to matter; I was looking for a way out of the world. Maybe we all are. Maybe that’s what religion is, people faced with a disappointing existence and looking for alternatives. The trick is to create them in the life you have, while you have it; to devote your body to yourself, and require something of it other than pain.

Saint Maud is available to stream on Hulu. mother! is available to rent on Google Play and Amazon.

Over at my other job, I recommended that men avoid the path of sinfulness by not covering up each other's sex crimes, even if they like each other very much. I also wrote about the end of Roe, and trying to own my body. Finally, for XTra, I wrote about transmasculine parenthood, what the word "dad" means, and why I would like that conversation to move away from "hey, trans people can get pregnant" to "hey, am I doomed to inherit the very gender roles that were used to harm me and, if so, how do I escape." Lots of smart people interviewed in that one, even if a smart person did not write it.

This has been a sad week, and I don't know if anything I could write would adequately express my sadness, but please read this.