Do Gay, Be Crime: The Talented Mr. Ripley (Anthony Minghella, 1999)

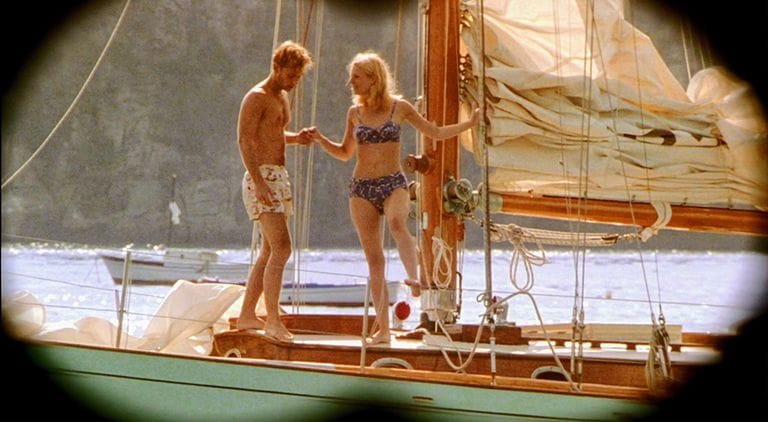

When you're both on a boat and one guy's skull gets smote, that's-a Ripley

First things first: This is not just about The Talented Mr. Ripley. It’s about The Talented Mr. Ripley and Ripley (Netflix, 2024) and Saltburn (Emerald Fennell, 2023) and Influencer (Kurtis David Harder, 2022) and… Ripley, like Alien and Fatal Attraction, has become its own genre. Its core elements — poor boy meets rich boy; gay boy meets straight boy; poor gay boy falls in love with rich straight boy, then murders him, then takes over his life — have entered the collective unconscious and spawned a half-dozen mutations.

That said, Minghella’s was the first Ripley I knew, and the only one I knew for a long time, so I’ll re-acquaint you with it before continuing.

Matt Damon plays Tom Ripley, a working-class kid with a talent for impersonation and forgery, who is mistaken for a Princeton student by wealthy boatmaker Herbert Greenleaf. Mr. Greenleaf’s son, Dickie, has shipped off to Italy (on a boat) and refused to return to the states (on a different boat) because he is too busy (on his personal boat) drinking and whoring and listening to Jazz. Tom lies to Herbert and claims to know Dickie, and so he is shipped off to Italy (on a boat) to retrieve him.

Upon arriving in Italy, Tom Ripley realizes two important facts: One, Dickie Greenleaf is played by Jude Law. Two, Tom is gay. Around half of the people in the theater probably had this same realization when Jude Law showed up, and you can’t blame them. Minghella has a knack for filming beautiful men in the same way that we usually film beautiful women, as pure astonishing spectacle, and it constitutes no small part of the film’s appeal.

Tom immediately falls in love with Dickie, despite the fact that Dickie is a narcissistic monster who spends his time breaking his fiancée’s heart, impregnating local girls and driving them to suicide, and storming the stage of local nightclubs in a drunken haze while attempting to play Jazz. You might think that no-one in the world would be sexually attractive after performing an impromptu Jazz song in a porkpie hat for their date, and you’d be right, for the most part, but it only makes Dickie Greenleaf more powerful. He’s a freak of nature in that regard.